Giant spiders, stuffed animals and monstrous performance: Weird worlds in Tate’s 2025 exhibition programme

A 30-foot spider looms over visitors, or stuffed toys spill out the walls. Animated monsters and dancers surround and taunt. Eerie videos of liminal digital worlds are projected on the walls. The Tate’s 2025 programme is filled with strangeness in the forms of sculpture, performance, fashion and video.

Louise Bourgeois’ renowned Maman spider sculpture is set to return to Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall for the museum’s 25th anniversary

When entering a modern art museum, there is a broad choice of what to see: puzzling minimalism, challenging politics or precise paintings. Often what is most attractive is something that shocks, amuses and transports the viewer into an alternatively imagined world, a reality of the artist’s mind. Louise Bourgeois’ renowned Maman spider sculpture is set to return to Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall for the museum’s 25th anniversary. The massive creature seems to be pulled straight from a nightmare and has both a brilliant weirdness and a psychological horror. It is exhilarating and terrifying and is just one of many strange pieces entering on the museum’s calendar.

Weirdness is an integral part of Mike Kelley’s legacy, seen in the current Tate Modern exhibition Mike Kelley: Ghost and Spirit, running until 9 March. His work is intentionally silly, creating different personas to allow his artistic identity to be ludicrously malleable. He dressed up as famous TV character, Banana Man, for a series of video works, but also takes on the character of an immature 14-year-old, graffitiing lewd images onto the Empire State building. Kelley claimed in a 1999 interview that he likes to ‘play games’, often seeming to trick the viewer, opting for something trashy and flashy in appearance, as opposed to a seriousness.

However, while indulging in absurdity, Kelley’s works are conceptually powerful and influential. The theme of memory recurs throughout the exhibition. He used the unconventional material of the stuffed toy, bringing to mind childhood gifts, or a sentimental connection to a beloved teddy. However, Kelley presents these cute stuffed toys sewn together, eliminating the personability of the individual playthings to create a horrible amalgamation, a monstrous dead mass. These works are often interpreted as engaging with childhood trauma, and in his lifetime, Kelley both rejected this reading, but also adopted it in later works, once again defying a singular artistic intention or identity. He also created meaning by building worlds, best seen in his investigation of Superman’s biography. Superman was born on the planet Krypton, which was destroyed except for the city of Kandor that survived by being shrunk into a small jar and left with Superman to protect for the rest of his life. Kelley claimed that he was not a fan of the Superman comics, but was inspired by someone who was burdened by his past. Kelley creates sculptures of this jar city, alongside a work where Superman reads Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar. The work is both poignant and ridiculous. It is almost a one-liner joke but does so craftily by mixing two cultural references. Being outlandish and bizarre is not just a part of Kelley’s work, but is his medium for reaching meaning.

Normalcy is abandoned; even her life takes on a performative aspect as Chetwynd changed her birth name from Alalia to Spartacus Chetwynd, then to Marvin Gaye and finally arriving at Monster

Mike Kelley, Eviscerated Corpse, taken by Marcus Stalmanis

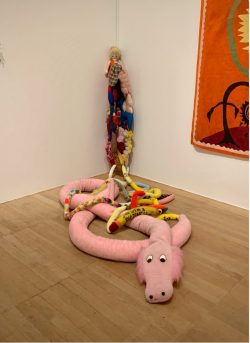

World building extends into Tate Modern’s Performance and Participant display with its new exhibit of Monster Chetwynd’s props, outfits and videos, A Tax Haven Run By Women (ending 18 May). Chetwynd is known for her energy and spontaneity, creating large monsters “impatiently” (in her own words) out of cardboard and papier mâché, and assembling performances of dancers and large-scale props in less than an hour before presenting to the public. She researches rituals and anthropology while also considering about monsters, entrails and insects. She doesn’t just offer distorted realities, but plunges the audience into absurd environments of exuberance and wonder. Normalcy is abandoned; even her life takes on a performative aspect as Chetwynd changed her birth name from Alalia to Spartacus Chetwynd, then to Marvin Gaye and finally arriving at Monster. Her strangeness is freeing and exciting. The sheer wildness of her work is a spectacle one is unable to look away from.

Monster Chetwynd, A Tax Haven Run by Women, taken by Marcus Stalmanis

If you are less into ritual dancing and more used to London clubbing, Tate Modern’s exhibition of the outrageous and revolutionary style icon, Leigh Bowery, is equally worth visiting (27 February – 31 August). Bowery’s colourful fashion and makeup looks seem wild and alien, with his performances being shocking, colourful and sometimes offensive. His career involved both running a wild club night, Taboo, as well as creating performance art, resisting categorisation in every way. His body became the art object from which he created his own insane world that saw Boy George described him as ‘modern art on legs’. Bowery’s influence on fashion can be seen everywhere, from Alexander McQueen to Ru Paul’s Drag Race, and his extravagant style is bound to be an exciting spectacle.

There is something stimulating about this unreal confusion, something freeing about delving into unknown territory. It is a good defence for artists being weird

Loud and vibrant fashion is a stark contrast to the quiet and melancholic strangeness of Ed Atkins’ video work, due to be exhibited in the Tate Britain (2 April – 25 August). He creates CGI spaces as sites for poetic exploration, such as an empty bar or a nebulous grey non-place of floating objects. His works are often inhabited by eerie human figures that are sometimes speaking or just existing in these spaces, as poetry is played in the background. Atkins’ work is elusive and cryptic, perplexing in its unintelligible narrative like in Ribbons (2014). The figure’s skin is incredibly detailed with every bump and fold, the tattoos are precisely etched into his face and body and dust particles fly in the air, soundtracked with a mix of musical composition, and ASMR-like speaking and sounds. Atkins’ worlds are undoubtedly artificial, but also hyperreal in the way it shows objects with such precision superior to the naked human eye (see Ben Lerner’s illuminating article The Pain Artist.) Atkins is often the subject of his work, motion capturing his own movements to create these digital avatars. There is a sense of uncanny to the emotion as it is hard to distinguish whether the subtle pain and melancholy is felt by this digital character, or if the avatar is a self-portrait representing the artist’s mind. Atkins’ captivating and mystifying works spark many conceptual questions of digital against reality, authentic and represented emotion, and the landscape of video itself, not leaving the viewer with many answers.

There is something stimulating about this unreal confusion, something freeing about delving into unknown territory. It is a good defence for artists being weird. Direct meaning is abandoned in these works in an effort to stretch the bounds of intelligibility. In return, we are able to experience a strange and complex world of the artist’s mind. Hopefully this year you go see these exhibitions in the Tate and can find beauty in the deranged or power in the strange.

Comments