From Beirut to Warwick, Angel Nakhle asks “Why is war always the answer?”

On 17 September, thousands of pagers across Hezbollah-controlled areas of Lebanon exploded. The assault would claim the lives of 42 people, including a minimum of 12 civilians, two health workers and two children. Estimates of those maimed ranged from 1,500 militants to 4000 civilians and later reports suggested plans for the attack had been formed over a decade prior.

It would come after almost a year of an intermittent exchange of fire between the Shia militant group and Israel, a front the former had opened in solidarity with Gaza following Hamas’ October 7 attacks that claimed the lives of over 800 Israeli civilians. Ten days later, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu stood in front of the UN General Assembly; “we’re not at war with you [the people of Lebanon], we’re at war with Hezbollah,” he claimed.

But Maronite Catholic and mixed villages were not spared by Israeli brutality.

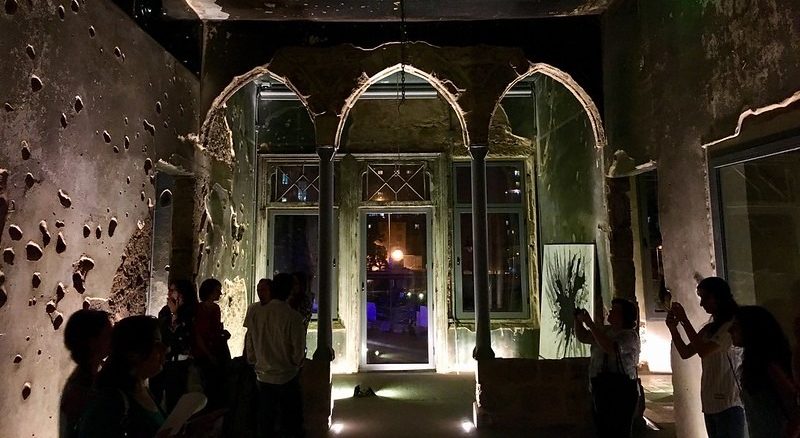

But Maronite Catholic and mixed villages were not spared by Israeli brutality. Images of destroyed churches flashed across our screens just as decimated mosques did. Church halls would take in displaced families as archbishops urged an end to the war. And 4,200km away sat Angel Nakhle, a Maronite Catholic and law student at Warwick, currently on her year abroad in France as entire suburbs of Beirut, the city she was born in, were levelled.

“They don’t care how many people they’re going to kill, they only see that goal – to erase Hezbollah,” says Angel. It’s a sobering statement but one that the families of the 4,000 killed, 16,000 injured and over a million displaced would likely attest to. The Israeli invasion ultimately led to the deaths of more than 200 children.

“What I care about is my people being protected, being able to prosper,” explains Angel.

Her people? I ask.

“Everyone,” she responds—an emphatic rejection of Lebanon’s sectarian divide. To Angel, identity transcends religion or sect; her ‘people’ are all Lebanese. That includes the some 1.5 million Syrians who fled a devastating civil war and found refuge in the country. “We’re known to be mixed—Muslims, Christians—we’re one of the only Middle Eastern countries that have that diversity,” she continues earnestly. “I love that about Lebanon. I think the Middle East needs more of that.”

Yet, while Angel embraces a unified Lebanon, she does not abandon her Maronite roots. Her Catholic faith, she confides, has been a source of great comfort throughout the conflict.

“I’m praying for this conflict to end, for the war to spare as many lives as possible, for there to be no more casualties, for peace to prevail,” she shares. In the face of destruction, prayer offers her solace, far removed from the chaos unfolding in Lebanon.

“Keeping my country in my heart—it’s something that really keeps me going,” she says, her words imbued with compassion and resolve. Though unable to help directly, these rituals give her a sense of contribution, a connection to her suffering compatriots.

“It is really hard when you see what’s happening, as a person. You’re living in the UK. It’s very safe, but then you see what’s happening. It’s just really heartbreaking,” she says, the weight of the situation palpable in her voice. “You feel so useless,” she explains, her voice cracking before adding, “It does break you a little bit, as a person.”

When you look at the news, you don’t realise those people that are dying also had dreams and hopes

– Angel Nakhle

And despite the overwhelming sense of helplessness, it is in her Lebanese identity that Angel finds a sense of responsibility. “What really motivates me is I need to make my country proud – I need to show people that Lebanese people are not just people you see on the news,” she explains, determined to shift the narrative.

Born into a post-9/11 world, most students at Warwick will have had little more than a first impression of near-constant conflict and political upheaval in the Middle East. So upon being asked if the region was too often condemned to eternal war, Angel jumped at the opportunity to shine a light on another side of the Arab world.

“When people think of the Middle East, they think of conflict,” she mourns. “Jordan is a welcoming country – they love to feed you,” she continues, a smile now touching her face. She paints a picture of a Lebanon where “people ask for your second name and they’ll know your family”. It’s a much more joyful, community-orientated side of life that, whether in peacetime or war goes overlooked by most Westerners in Angel’s view.

It is the Lebanese spirit of persistence that she admires most: “We want to contribute to the world — when you look at the news, you don’t realise those people that are dying also had dreams and hopes,” she says, albeit in a tone tinged with sadness.

“No privacy though – you can’t escape,” adds Angel with a laugh that punctuates her evident affection for her homeland. “The culture, the community, they’re the things I really miss.”

What I really don’t understand, genuinely, is why war is always the answer

– Angel Nakhle

However, she feels Western discourse often perpetuates harmful misconceptions; “the Middle East is judged very easily – people don’t go to the Middle East because they think it’s dangerous”. In some ways, Angel suggests, it is an attitude linked to the lingering effects of colonisation: “The Middle East will never have peace until they become like the West,” or at the very least, she believes, until there is peace between Israelis and Palestinians.

And in the midst of these “heartbreaking” events, Angel holds onto a message of hope and empathy. “What I really don’t understand, genuinely, is why war is always the answer,” she says, accompanied by a clear frustration. “It just brings more destruction, if Israel’s goal is to erase Hezbollah, trust me, they’re not going to erase it that easily – they can come to an agreement together.”

Angel is all too aware of the political and military strength Hezbollah wields. Formed in the 1980s during the Lebanese Civil War – initially to resist Israeli occupation – the Shiite militant group is regarded as a terrorist organisation by many countries, including the UK.

Its influence remains a divisive issue amongst Lebanese Christians. Whilst some view Hezbollah’s militancy as a necessary form of protection against foreign threats with a weakened national army, others reject its violent tactics and ties to Iran and were hesitant to support the group’s dispute with Israel. The group have been responsible for the deaths of over 100 people in northern Israel since 8 October 2023, including 46 civilians.

Yet despite the difficult position Maronite communities have found themselves in, Angel remained resolute in speaking up for an end to the war.

“You see it everywhere – signs that are for peace, for Palestine, for Lebanon”; she gestures towards a growing wave of activism in response to the conflict. It’s an observation that would be familiar to all students as encampments in solidarity with Gaza were erected globally whilst Warwick Stands With Palestine have continued their attempts to disrupt university life at home.

Angel’s message is not a rejection of those that campaign for their version of justice in Palestine, Lebanon and the wider Levant region but rather a plea for empathy from those who perhaps feel detached from the cause. “I think what makes people scared is taking sides,” she explains. It is perhaps a timely discussion to be had as well; a Boar survey from June suggested almost half of Warwick students felt student politics ‘had become too toxic’.

Meanwhile, thousands of kilometres away from campus discourse, hundreds of thousands of Lebanese pupils were forced to put their education on hold as schools were converted into shelters for the displaced. In Gaza, there was no class of 2024; every university in the strip had been bombed by Israel by just the hundredth day of the onslaught.

“Education is a human right. We’re seeing these kids not being able to exercise one of their human rights,” she posits, her law studies particularly evident here. Angel’s advice to fellow students is a simple but powerful contemplation of the ease of detaching oneself from the horrors of the conflict with Western comforts: “Even if don’t do a lot, talk about it, spread awareness on social media. Have a discussion about this – keep these children in mind,” she urges.

It stands as a stark reminder of our responsibilities towards others, regardless of whether one feels intimidated by the arguable complexity of the political context

“I don’t blame anyone.” Seeking to antagonise those who disagree but have no power, in Angel’s view, is an unnecessarily divisive attitude — futile even. “Who should be acting right now is the government, people in power—people who have things that they can change,” she asserts.

Yet it is by no means a condemnation of the role of protest: she maintains that change can start “if we keep pushing [for peace] as people, as students who have a platform”.

Angel also urges students to “realise their privilege,” acknowledging her own struggles. “Being grateful—it helps you cope with your own education,” she reflects. “I know education is hard, it also pushes you. Once I get educated, maybe I can do something in that area later on in life, to give back.”

Her message serves as a more unique call to action, one that goes beyond choosing a side and urges all students to use their platforms to advocate for peace and to remember the children who are losing their futures to war. It stands as a stark reminder of our responsibilities towards others, regardless of whether one feels intimidated by the arguable complexity of the political context.

But misinformation and fear can shape public perception in powerful ways—often with dangerous consequences. This became painfully clear last summer, when riots erupted across England in response to the Southport stabbings that claimed the lives of three young children. Within a day, false claims that the perpetrator was a Syrian refugee had circulated rapidly online.

Angel, now living in the Black Country, came to the UK from Lebanon as an asylum-seeker, so the events of the summer hit particularly close to home.

“It’s instilled fear in me, it was really shocking” she recalls. “I did not expect a lot of people to come out and be clearly and blatantly against [those seeking asylum in the UK]”. As hotels were set alight, mosques attacked and libraries looted, Angel, like many students of colour last summer felt deeply fearful in even stepping outside: “I was afraid of what might happen. I had to go to Manchester for my Visa appointment.”

“It’s something I’ve never witnessed before. I was scared going out on buses, going out on the street,” she admits, describing a sense of unease that permeated her daily life in the weeks following. The illogic of the rioters’ claims seemed so clear to the student, so when such horrific violence broke out across England, it was difficult to comprehend the scale. “It was so hard to witness. I don’t understand the guy who committed the crimes, he was Christian – but it was hatred towards Muslims,” she reflected on the contradictions of the violence.

Perhaps most poignantly, despite the fear and confusion she experienced, Angel’s instinct was to return to the real tragedy: the loss of innocent young lives in the stabbings themselves. Much like when she spoke about Lebanon and Gaza, her focus remains on the human cost of violence. “They’re just kids. They should be at home doing their homework or playing outside,” she laments.

Angel gives us a lesson in leading with empathy and thoughtfulness for all

Even in discussing the children who did participate in the riots, she seeks to reflect on the deeper forces at play, wanting to spotlight the dangers of “what kids are exposed to on the internet — what makes them commit these hate crimes”. Their anger, she suggests, is being misdirected. “The government and the media are to blame for portraying immigrants as the problem.”

“I’m also a person with dreams and hopes,” she adds. “I’m not here to steal anyone’s job. I’m here to give back to a country that made me feel at home.”

It is in this approach, perhaps, that Angel gives us a lesson in leading with empathy and thoughtfulness for all: for the Israelis waiting hundreds of days for the return of their kidnapped relatives; the Palestinians starving in tents outside dilapidated hospitals and the Lebanese mothers burying their baby monitors in gardens, fearing they could explode at any moment. As she puts it, “It’s for the children, at the end of the day”.

“It’s really important that people, especially students, keep them in our mind. It is a privilege that we are studying. I’m able to study at Warwick, to pursue my dreams, whereas a lot of Lebanese people right now are in camps, they’re displaced — it’s sad to see.” And in the context of this conflict, Angel’s own Maronite community, unrepresented by Hezbollah, is often forgotten whilst the fragile ceasefire struggles to hold. So armed with respect but little envy for those who devote their time towards anti-war movements, she jokes, “I’m so glad I don’t do politics.”

Comments