OBR Chair addresses students at the University of Warwick

The “three great challenges of our time” are demographic change, climate change, and global disintegration.

That is what Richard Hughes said when addressing students at the University of Warwick. Hughes chairs the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR): an independent public body that monitors the government’s fiscal policy and assesses the UK’s economic performance.

Speaking on 6 November, Hughes’ keynote was hosted by the Warwick Economics Summit (WES) as part of its ‘WES Presents’ speaker series. It occurred following a careers fair run by Warwick’s Department of Economics.

Demographic Change

Demographic change is the “most certain and well understood” of our current issues, Hughes argued.

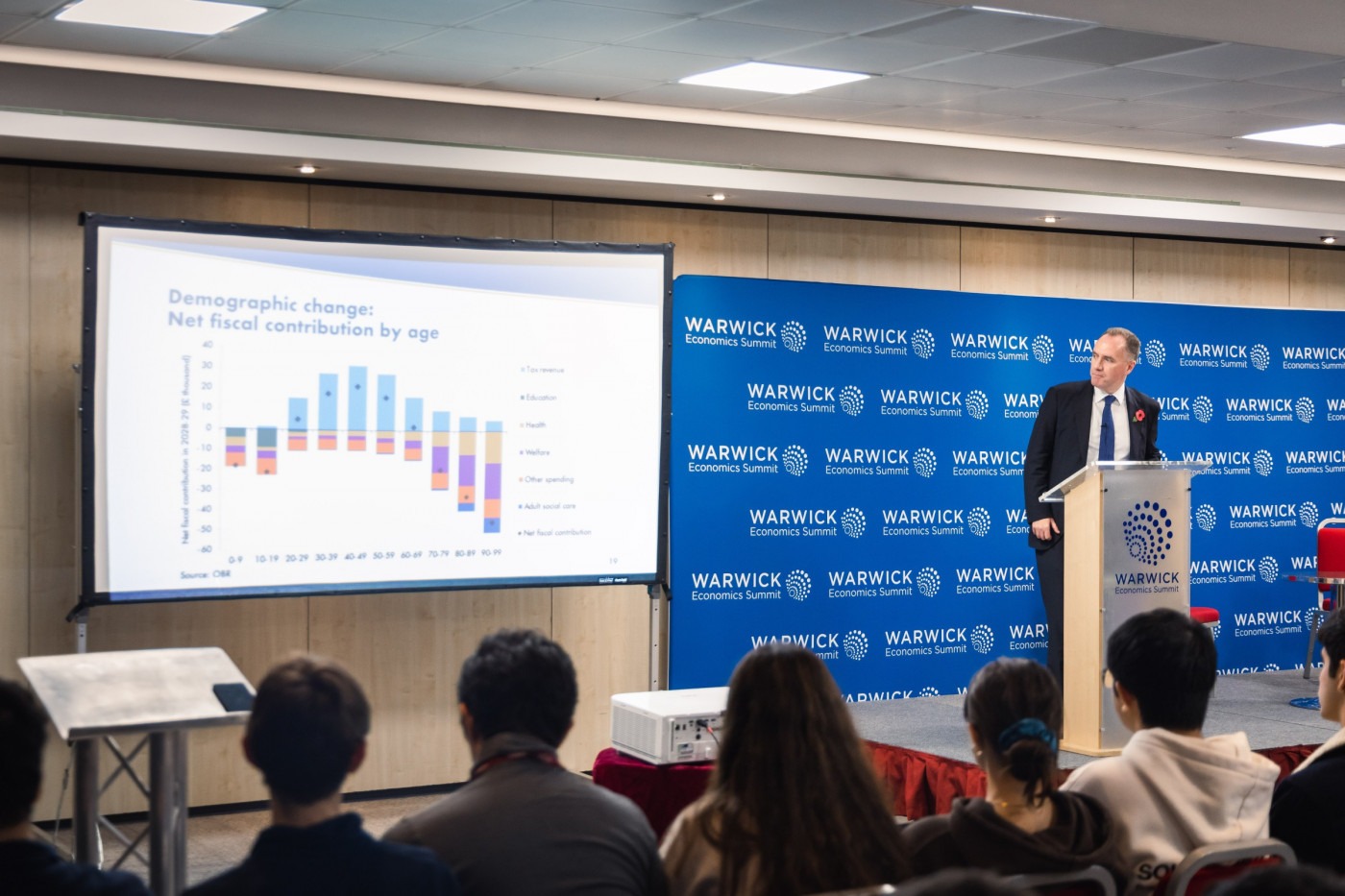

By 2074, the OBR estimates the UK’s ratio of working-age individuals to retirees will fall from four to just two. Furthermore, the OBR’s definition of working age, 16–64 years old, is not a true representation of the number of people working and paying tax, since many individuals remain in education until they are 21. Accounting for such a distinction only worsens our demographic outlook.

This demographic shift will enlarge the burden upon young people, as the government may have to increase taxes to finance higher spending whilst stemming the need for borrowing.

“Getting old is an expensive business in terms of public finances”

Richard Hughes, Chair of the OBR

The need for higher spending derives from the growing demands on the State Pension, NHS, and adult social care that population ageing will exact. In 2022/23, the government spent nearly £182 billion on the NHS, and this number will only grow in the years ahead.

According to OBR projections, if the tax system remains as is, revenues will stay “broadly constant” at approximately 40% of GDP. However, due to demographic changes, government spending is forecast to rise to roughly 60% of GDP by the 2070s. This gap between tax receipts and spending means, if “public services are left on autopilot”, the UK’s debt-to-GDP ratio could reach 200% of GDP by the 2060s. This is assuming that there are no economic shocks, like Covid-19.

This outlook led Hughes to remark: “Getting old is an expensive business in terms of public finances.”

He argued that acting early on demographic change by tackling health is “probably the single biggest thing you could do” to resolve the demographic issue. Hughes is an advocate of “healthy aging”, meaning that if people are more active and eat healthier, the fiscal effects of a larger retiree population will be more manageable. However, he argued “that process seems to be going in the wrong direction”.

Climate Change

Hughes asserted that the UK is “relatively insulated” from the broader impacts of the climate crisis.

Modelling by a consortium of central bank implies a 3% GDP loss by 2070-71, even if we keep the rise in global temperatures to 2°C. This rises to 5% if we end up in the 3°C scenario.

Combined with higher debt interest costs, alongside the direct and indirect costs of climate change, this will increase public indebtedness. Another 20-35% of debt, as a percentage of GDP, could be added to the public finances if the rise in global temperatures rises above 2°C but below 3°C.

Government has “huge coordinating power” and the “power of purse strings” to address climate change

Hughes also explained how firms and households needing to buy insurance in response to climate change will be a burden on the UK’s economic potential, reducing economic growth and raising debt levels.

This highlights just how crucial climate action is. In this regard, he suggested government has “huge coordinating power” and the “power of purse strings” to address climate change.

Hughes said that over the next 50 years, it will cost 20% of GDP to achieve net zero. Moreover, the direct costs, such as green energy subsidies, are relatively small. The primary financial impact is the loss in tax revenue from fuel duty, amounting to around £30–40 billion annually. Hughes offered a solution — taxing carbon emissions “to help replace revenue lost from fuel duty”.

Geopolitical Disintegration

The risks presented by geopolitical disintegration are relatively more uncertain, depending heavily on the behaviour of political actors.

Free trade – or geopolitical integration – has been the “most powerful engine for raising living standards in history”. However, new protectionist measures on trade are outpacing liberalising measures “at a rate of nearly four to one” according to Hughes – far from the heyday of trade liberalisation in the noughties. Due to disintegration, it is now “unlikely” that the UK will return to pre-2008 levels of productivity growth.

The US has had no such issues and has enjoyed far higher productivity growth post-2008 than Western European economies. America’s large domestic market facilitates economies of scale and can enable companies to extensively test their product before going global. Moreover, Hughes explained that the US’ greater exposure to the “harsh winds of the free market”, such as greater access to financing and different bankruptcy laws, meant that it has been able to adapt more smoothly to the new paradigm. America also remains the research lab of the world, accounting for 32% of global R&D spending, and the resulting intellectual property means the US can compound its advantage.

“We [the economists] have clearly been losing the battle of ideas”

Richard Hughes, Chair of the OBR

Hughes noted that trade “makes a huge difference to the productivity of firms” in the UK. Similarly, the integration of China into the global trade market has “transformed living standards” in China. Since 2001, the date of China’s admission into the World Trade Organisation, its Human Development Index has risen from 0.593 to 0.788 in 2022 – a rise of 39 places in the world rankings.

“The world has experimented with trade barriers and we know how that ended up”, added Hughes, referring to the disastrous Smoot-Hawley Act passed by US President Hoover in 1930. The act decreased US exports and imports by 67%, worsening the impacts of the Great Depression.

Despite this, the electorate is not convinced: Hughes noted that “we [the economists] have clearly been losing the battle of ideas” when it comes to free trade. We need to “bring stories to life” to convince people that there are tangible benefits to trade liberalisation, by pointing out examples such as the integration of Eastern Europe into the EU and the costs of protectionism to industry.

Hughes suggested institutions that have historically been the pillars of trade openness and integration, such as the IMF and WTO, are heavily reliant on America. The election of Donald Trump on a highly protectionist policy platform may undermine them, leading to fears that global leaders are questioning the value of those institutions “just as they are becoming more valuable”.

Barriers to Rationality

As economists, we have a “fundamental faith” in human rationality, but Hughes identified three bounds to this rationality that we should strive to overcome.

The first is uncertainty, which Hughes says is “maybe not such a big problem”, but that can be solved through highlighting the benefits of early and decisive action, such as on demographic change. Myopia, the second barrier, can similarly be overcome by estimating the long-term cost of inaction. Problems of collective action, or as Hughes call them, “nobody but everybody’s problem”, must be solved through dialogue highlighting the payoffs of working together.

For economists to overcome the three great economic challenges of our time, we must also convince the public and policymakers to overcome the three great bounds to rationality.

Comments