Decluttering the ‘mancave’: How projects like Warwick Arts Centre’s ‘Community Talking Shed’ are using collaborative art to fight the mental health crisis

What is it with men and sheds? Maybe it’s the fact that they provide an easy refuge down the bottom of the garden, where men (especially dads) can shut themselves away from the world, tinkering away at their latest DIY obsession. Warwick Arts Centre’s ‘Community Talking Shed’, however, was a different sort of ‘mancave’, whose doors were open and inviting, rather than fostering seclusion.

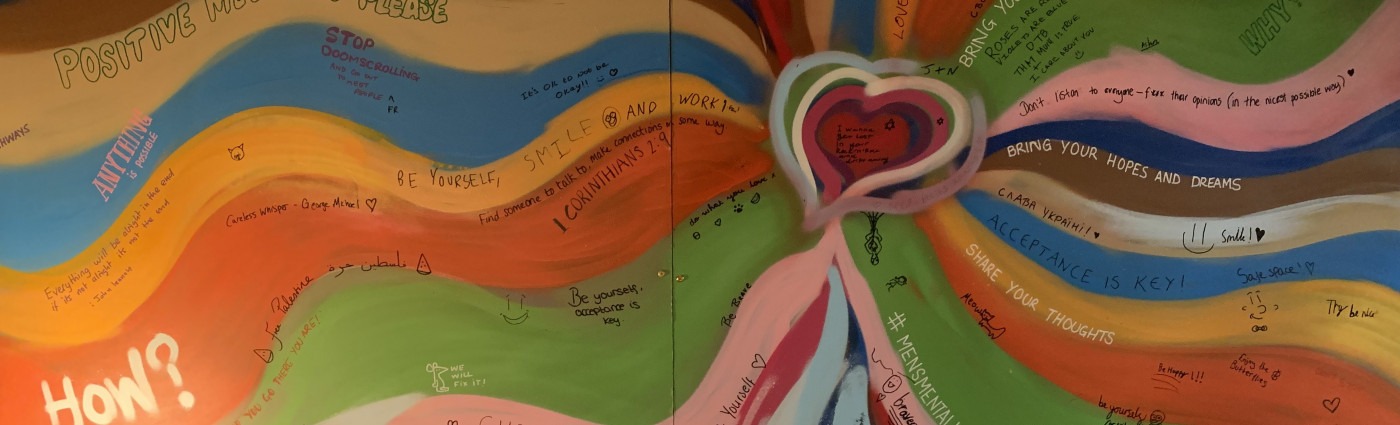

The temporary art installation, a collaboration with the charity It Takes Balls to Talk (founded in the Coventry and Warwick area in 2015), aimed to encourage brotherhood and vulnerability amongst men during the Movember period. Looking inside the Shed one Tuesday afternoon, I didn’t find toolboxes and dusty trinkets, but instead heartfelt and motivational murals covering the walls, and leaflets directing those who entered to vital support networks. For such was the Shed’s purpose in November; to show that visitors were not alone and that, beyond the pressurised mental health bubble, there is a community of willing friends waiting to listen, if only one opens their shed doors to the sunlight.

The local community has thus quite literally made its mark on the Shed – fitting for an installation designed to make the concept of community tangible, especially for men

The colourful inside of the Shed, painted by street artist Michael Batchelor (Instagram: @dynamickart), shows a mural of a hand touching a dejected man’s shoulder, the voice beyond the picture saying, “don’t worry, you got this”. Another vibrantly painted wall contains the messages of those who have previously entered the structure, constituting an archive of the Warwick and Coventry community’s presence within the Shed over recent weeks. Many of them have inscribed the colourful walls with their encouraging pearls of wisdom. Some have directed onlookers to Bible passages, while others have simply written messages like “choose love”. Someone’s transmission of a John Lennon quote was particularly effective: “Everything will be alright in the end. If it’s not alright, it’s not the end.” The local community has thus quite literally made its mark on the Shed – fitting for an installation designed to make the concept of community tangible, especially for men. The Shed will now be donated to the community as a legacy project, continuing its impact up until now.

Kate Walters, Programme Manager at Warwick Arts Centre said: “Suicide is the biggest cause of death for men under 45 and, with a team of clinicians and community workers, we are taking the conversation out into our public foyers to meet people where they are.” The Talking Shed is the latest in a line of similar projects, intended as workshops where men can connect and socialise – recreating, upcycling, and supporting the community along the way. The Shrewsbury Men’s Shed, for example, was previously a stable block at the West Midlands Showground. After being repurposed as a shed (and admittedly a far larger one than the Arts Centre’s), it now houses workshops, a greenhouse, a commercial kitchen, and a patio area. The sheds do more than simply act as stationary wooden structures. They inject life into villages and towns, mobilising locals through projects that harness their dormant creativity and provide meaning to those struggling to find it. One might say that, unlike your typical shed, these ones encourage a decluttering of the anxious mind, not a hoarding of futile worries.

Its tenure as sentry in the Arts Centre foyer, along with the imprinting of hope on its walls, was artistic proof that community can be made not only imaginable, but also real when people come together and when creative energies converge

Simon Rouse, from Shrewsbury Men’s Shed, said that the shed groups meet “an unmet need”. “There’s a crisis,” he lamented, “and while men won’t seemingly go to preventative health initiatives, or won’t go to lots of charities, they seem more than willing to go to a men’s shed.” The breadth of the movement was only confirmed by the Shrewsbury Shed taking home ‘Shed of the Year’ at an awards ceremony held at the House of Commons. Who would’ve thought that such a prestigious title existed? But, given the vital work being carried out by the shed movement, a baton recently picked up by Warwick Arts Centre, it is easy to see why the cause has garnered such plaudits from on high.

Dr Alex Cotton MBE, founder of It Takes Balls to Talk, described the fundamental drive behind campaigns like this: “Having worked in NHS Mental Health Services for 32 years, I have seen that people are not always aware of what to do for themselves or others in a mental health crisis. If I were to give you three words to describe what It Takes Balls to Talk does, they would be, prevention, prevention, prevention.” Dr Cotton gave a suicide awareness talk at the Arts Centre on Tuesday 26 November, reaffirming the pressingly real emergency behind the doors of what seems at first glance to be a quaint wooden hut.

However, the Shed’s urgent directive to the local community is ultimately one of hope. Its tenure as sentry in the Arts Centre foyer, along with the imprinting of hope on its walls, was artistic proof that community can be made not only imaginable, but also real when people come together and when creative energies converge. Hopefully its re-homing away from the Arts Centre doesn’t signal the fading of the values it was built on, because the mental health crisis demands strong support networks, not rickety ones. With luck, it can continue to provide a space for reflection and illumination for future passers-by, wherever it finds itself steadfastly standing. ‘Mancaves’, perhaps, can be more than we think.

Comments