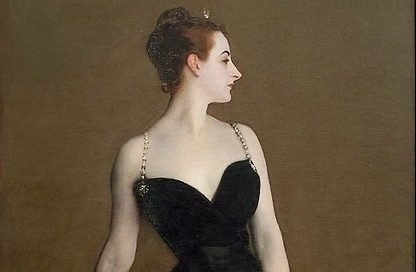

Fallen straps and broken mirrors: The scandal of Sargent’s “Portrait of Madame X”

“Mr Sargent made a mistake if he thinks he expressed the shattering beauty of his model… we are shocked by the spineless expression and the vulgar character of his figure,” declared French newspaper L’Événement in the days following the unveiling of John Singer Sargent’s now-iconic Portrait of Madame X. Another quipped that had one stood before it at its 1884 debut, they would have heard “every curse word in the French language.”

The painting now has pride of place in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, but its initial reception not only earned Sargent such an infamous reputation he fled to London in response, it also prompted him to hastily repaint it to salvage his tarnished image. It would forever alter the trajectory of his career.

A study in opposition, the artwork features a striking, porcelain-skinned woman in an elegant black gown, with a paleness that glows against its dark background. In parallel, the dress’ modest length stood opposed to the revealing straplines that hint at an alluring sensuality. In fact, the original exhibition depicted one strap scandalously dropping from the figure’s shoulder. This aspect was perhaps the most outrageous detail of all to contemporary audiences. So much so that it was later repainted by Sargent to preserve the very remnants of ‘Madame X’s modesty. Some critics even highlight the inclusion of the table the figure rests her hand on as a means of accentuating the curves of the subject that angered 19th century audiences so intensely.

The portrait was not a commission, but rather the subject of an obsession of Sargent’s

Do not be fooled by the apparent anonymity of Sargent’s ‘Madame X’: its title only served as a thin veil for the identity of Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau. A New Orleans-born Parisian socialite, she had gained notoriety across Parisian society for her stunning beauty and impossible pallor that art critics would later label “ghostly”. One American painter, Edward Simmons, said of his fascination that he “could not stop stalking her as one does a deer”.

Unlike most, the portrait was not a commission, but rather the subject of an obsession of Sargent’s and involved a pursuit of the socialite likened to a “full campaign” by art historian Deborah Davis in her 2003 book Strapless. The opportunity to paint Gautreau then, was a prize in itself for the artist, but neither anticipated the firestorm that would follow.

And the socialite’s resistance to being painted did not end upon agreement either, supposedly restless, impatient and unconvinced by John Singer Sargent’s determination throughout the process. In one letter to a friend of his, Vernon Lee, he lamented that he was ”still in this country house struggling with the unpaintable beauty and hopeless laziness of Mme. Gautreau.”

Then, over one arduous year later, it would come time for the debut of the then-called “Portrait of Mme ***”, whose perceived vulgarity would horrify the public and attract allegations of attempts to manufacture scandal. For Sargent, French commissions dried up almost entirely pushing him to eventually move to London to attempt, admittedly with a fair degree of success, to revive his tainted career.

Gautreau herself was not spared from the fierce public outrage either, with the anguish leaving the figure so unable to bear looking at herself that she reportedly destroyed every mirror in her own home. Her portrayal by Sargent had confirmed an image of promiscuity that only served to amplify previous Parisian whispers of her affairs with prominent French statesmen. She ultimately retreated from Parisian society for the rest of her life.

Today, the legacy of the painting itself is somewhat disputed

But 32 years later, in 1916, Sargent himself would describe the infamous portrait as “the best thing” he had ever done, offering to sell it to the Met where it now hangs, yet the scandal refused to fade from public memory.

To this day, the legacy of the painting divides opinion; Sargent’s artistry has continued to be overshadowed by these stories of the intense public furore and challenges to late 19th century standards on modesty. Not everyone has been willing to elevate the portrait to masterpiece status: one mid-century American critic Hilton Kramer didn’t see the portrait as having any “significant aesthetic merit” at all.

Nonetheless, it is perhaps in the fashion world where Sargent has left his greatest artistic mark, despite the best efforts of many Parisians to erase his name from the art history books altogether. The elegant dresses that featured not only in this portrait but many of his works, continue to inspire fashion today, even motivating a dedicated Tate Britain exhibition this year.

Comments