Tracing Roots: A Journey to Uncover my Windrush Legacy

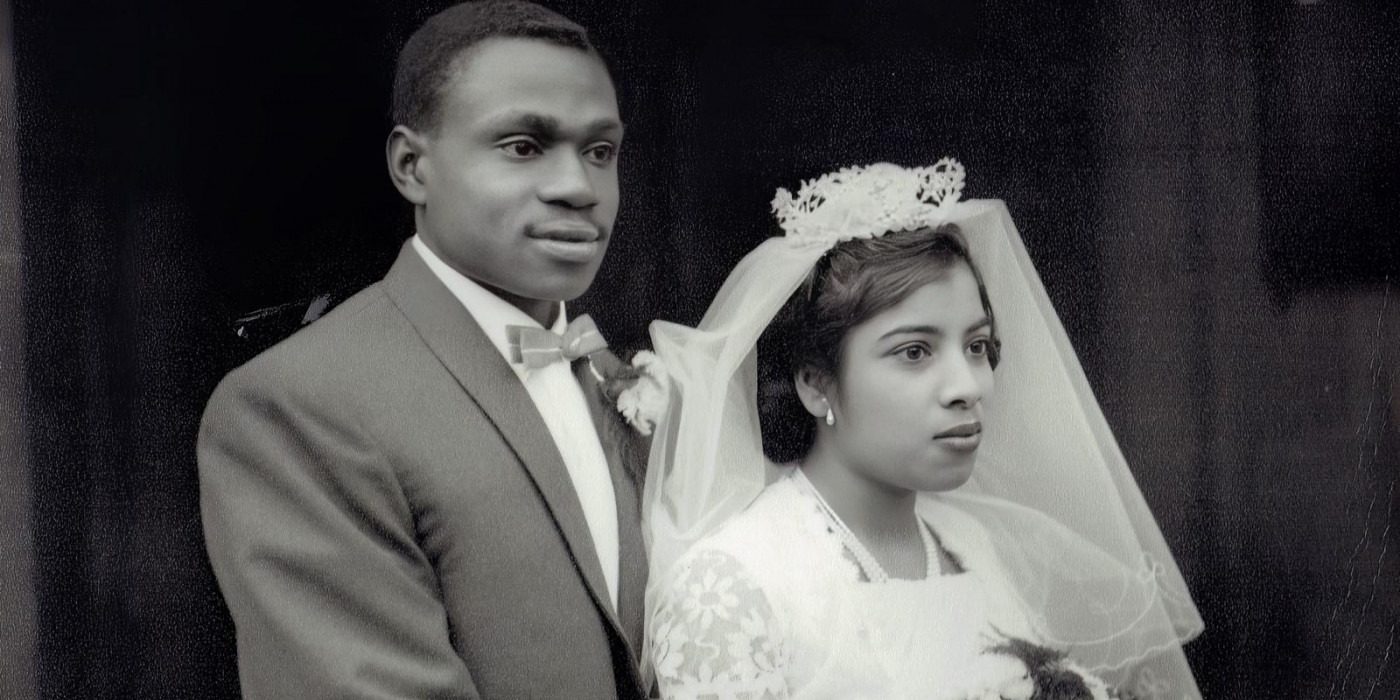

Sixty-three years ago, in 1961, my grandmother, Janet Watson, left Geddes Town in the parish of St. Mary in Jamaica to come to Britain. In her 82 years, she has presided over three children and seven grandchildren. Watching her step onto the Tarmac in Montego Bay Airport, the weight of three generations of history was endemic. Those small, shuffling footsteps demarcated a journey of over seventy years, one which extends far beyond me. Yet, I came to the country to explore a history and a legacy that has made me who I am.

The namesake ‘Windrush Scandal’ in 2018, instigated by the Home Office in Britain, was one that tore hundreds of families apart.

In 2024, the epithet ‘Windrush’ evokes a whole suite of connotations. The term and the narratives of the figures, figures like my grandparents, who arrived in post-war Britain, cannot be disentangled. The ‘Windrush Scandal’ in 2018, instigated by the Home Office in Britain, tore hundreds of families apart. Caribbean migrants who had spent the best part of their lives as part of the beating heart of Britain were now being rejected by a nation they had called their mother.

The challenge of citizenship for members of the Caribbean population in Britain, and the further threat of deportation, showed a fundamental misunderstanding, and unawareness, of the history of Britain in the late 20th century. A history that has shaped the country as it exists today. An ocean away from the curriculum at either my primary or secondary school, I had also been rather ignorant of the nuance of this history. This was until one of my lecturers at the University of Warwick inspired me to rethink this.

After doing a family history module, I came to the profound realisation that I was vastly lacking in an understanding of the contours of my grandparents’ journeys to the country. The broader significance of them uprooting their lives to traverse the Atlantic Ocean, and landing in Britain, was also something that had been lost over the years. I left that class knowing I had to consciously try to better understand the journeys that had started two family lines.

Between 1948 and 1971, it is estimated that over 500,000 people travelled to Britain as part of what has now been termed ‘The Windrush Generation’.

Three months ago, whilst wading through the deluge of university emails that inundates my laptop, I found a notice for the University of Warwick’s Undergraduate Research Support Scheme, commonly known as the URSS. It is a program that awards funding for extensive investigative work outside of a typical degree curriculum.

Equipped with a gnawing inner desire to find out more about what had brought my family to Britain, I was struck by an epiphany: I would use the URSS programme to answer these growing questions and get a greater understanding of the history of a wholly underrepresented people.

Between 1948 and 1971, it is estimated that over 500,000 people travelled to Britain as part of what has now been termed ‘The Windrush Generation’. In June 1948, the SS Empire Windrush left Kingston in Jamaica and docked at Tilbury in London. The, now notorious, vessel carried approximately 802 Caribbean migrants who marked the onset of further island natives, coming to Britain in search of a better life.

Speaking to my grandfather, Clan Ebanks, a month and a half before I visited Jamaica, he had told me that when he had left for England at 18 he had believed that the streets were paved with gold. Now 90, he can see both the ignorance and courage of youth in his decision to leave his home. The hope of a land of endless prosperity seemed to be widely held among the members of that generation.

A successful URSS application afforded me a full grant to be able to travel to Jamaica through the University.

A successful URSS application afforded me a full grant to be able to travel to Jamaica through the University. This signalled the fulfilment of a now four-month-long wish to understand my own story, a decade after I had visited the country as a young boy. It was at this stage that my grandmother indicated that she wanted to come with me. This small, and at the time relatively matter-of-fact, request would go on to change the entire nature of my project and my visit, in a way that was both unexpected and deeply profound.

She had not seen her native country for eight years, in which time her youngest brother had unexpectedly passed, rekindling her desire to see her childhood home once more. Coming to Jamaica at the beginning of June, I realised that months of meticulous planning and attentive research could not prepare me for the raw majesty of the landscape and the complex, pure, and unburdened beauty of the people I met.

I stood beside her, breathing in a legacy and ancestry that I could never fully know but at the same time was closer to her than I had ever been before.

On the first full day of my trip, my grandmother took me to the site where her parents were buried. Shrouded in dense weeds and thick foliage, in a fenced-off area at the back of someone else’s property, was a stark reminder of both the inequality in the country and the extremely privileged position I find myself in. I stood beside her, breathing in a legacy and ancestry that I could never fully know but at the same time was closer to her than I had ever been before. I could feel a flood of emotions contorting inside of me.

After a few minutes, my grandmother and I left the property, thanking the new owner for allowing us the time to pay our respects. I could see the pain and held back tears written on her face. It was at this moment that the full weight of the sacrifices made by not just my grandparents but all the generations before them rested on me. My story is that of a line of ancestors who undertook menial farm labour, and before this, enslaved labour on plantations in parishes across Jamaica. However, this is not just my story. This is also the story of a vastly nuanced, vibrant, and driven Caribbean population present in Britain today.

I am now of the opinion that it is almost impossible to conceive of the importance of one’s own history without having a tangible stake in it.

I am now of the opinion that it is almost impossible to conceive of the importance of one’s own history without having a tangible stake in it. Seeing the country that made me with fresh eyes shattered a lot of my preconceptions about who I am and how I live. Although I have always been proud of my Caribbean heritage, it has been something I have always worn quite lightly, not appreciating or necessarily valuing the depth and significance behind it.

The trip in its entirety was far from easy, but I know now it was one that I had to make. I have always been interested in the idea of the past and the present being intrinsically connected. The phrase ‘you will understand when you get older’ is seemingly as old as time in my family, passed down from father to daughter, from mother to son. The meaning of it was not lost on me though in the time I was able to spend with my grandmother on the island. I know that she will not be with me forever, but when I am older, it is her legacy, and the boundless and devoted strive the Windrush generation had, that I will remember.

I know that thank you is not enough for my own grandparents, and the countless others in the Windrush generation who gave up everything to change the trajectory of their lives for their families, but it is a start.

I know that thank you is not enough for my own grandparents, and the countless others in the Windrush generation who gave up everything to change the trajectory of their lives for their families, but it is a start.

Comments (2)

Am seeking some information about how to go about doing an historic investigation about my father…he went to work in England during Windrush Between 1948 and 1971

Am seeking some information about hoe to go about doing an historic investigation about my father…he went to work in England during Windrush Between 1948 and 1971