Why We Must Remember Peter Magubane

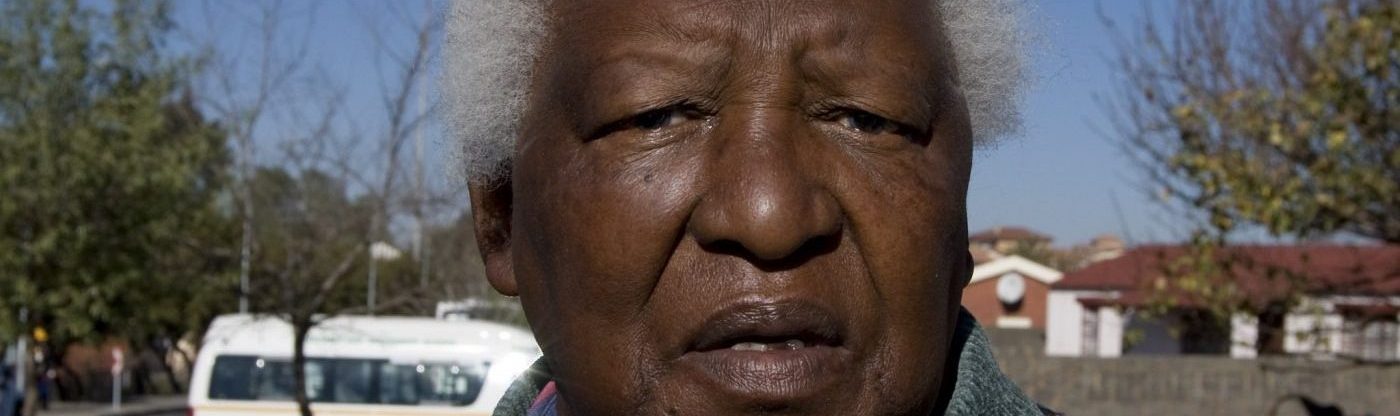

When we think of photographs or cameras, many of us might imagine an iPhone, a pretty sunset, or Instagram posts. For Peter Magubane, a photograph was much more than a quick snapshot of aesthetically pleasing latte art. For him, his camera was a weapon against almost 50 years of racial subjugation. Perhaps some people might question the equation of a compact, rectangular device with an instrument of deadly destruction. Such people would benefit from transcending their present-day realities and positioning themselves within the socioeconomic context of the South African Apartheid. Peter Magubane used his camera to capture ineffable violent atrocities, intense racial discrimination, and insurmountable injustices during this period. He saw it as his mission to communicate the brutal realities of South African Apartheid to the world with a still image. His photographs had the power to transcend the confines of their one-dimensional form and uncover years of ethnic oppression on the basis of racial superiority. For those of us who did not know Peter Magubane on a personal level, the best way for us to memorialise him is to acknowledge the power of his life’s work.‘I was going to stay and fight with my camera as my gun. I did not want to kill anyone, though. I wanted to kill apartheid’

The National Party’s ascendance to government in 1948 marked the ‘apartness’ of white and black South Africans by law. Apartheid ostensibly called for segregated but equal development. Instead, it was a tool to subjugate black and ethnic minorities in favor of white superiority. Significant legislation includes the Group Areas Act in 1950 which enforced the removal of black people from their area of residence into their ‘homelands’. Essentially it was an effort to preserve all white areas. In addition to intense segregation, black South Africans were also subject to violent brutality at the hands of white police enforcement. Peter Magubane was not immune to such brutality. In an interview with the Guardian, Peter recalls how he was ‘arrested many times and the police beat the hell out of’ him.

Peter Magubane used his camera to capture ineffable violent atrocities, intense racial discrimination, and insurmountable injustices

After being subjected to a five-year banning order in which he could not work, Magubane attended the Soweto riots in 1976 with a ‘vengeance’. He convinced protesters to be photographed by declaring that ‘This is a struggle; a struggle without documentation is not a struggle. Let them capture this, let them take pictures of your struggle; then you have won.’

With these words, Magubane highlights the importance of photography in political movements. Politicians are especially good at twisting words and manipulating facts. For instance, the Nationalist Party could deny the injustices of apartheid by consulting what was written in the law (separate but equal living), rather than what was done in practice. However, through the efforts of photojournalists, the truth of Apartheid was delivered in black and white. As human beings, we often have the proclivity to deny, undermine, or ignore what is not right in front of us. Peter Magubane made sure this was not the case for Apartheid.

In line with documentary photography and photojournalism, Magubane’s work depicts real-life occurrences, using a single snapshot to elicit a poignant message: that apartheid must end. One of his most notorious photographs depicts a small girl sitting on the ‘European’ side of a bench, with her maid sitting on the ‘black side’ of the bench. It is a simple image, but it tells the story of draconian rule, of an infringement of liberties whereby something as simple as being seated on a park bench is politically controlled. It tells the story of the human condition, which knows no racial bounds. It is not only an informative photograph, but also a poignant art piece.

Magubane recounts that he did not ask for permission when taking the photo of the black maid and the white child. He did not ask permission when taking any of his photos. By only focusing on the raw, unstaged truth in his photography, Magubane can narrowly avoid the discourse surrounding objectivity in photojournalism. Nevertheless, many also dispute the integrity of photojournalists for their ability to determine what is shown and what is not shown in an image. However, Magubane’s work goes beyond the discourse of realism and objectivity. His ability to combine the objectivity of his camera with his subjective attitudes towards apartheid acted as a force of resistance against white power. It is an indication that often, purposefully choosing to depict marginal or silenced voices is in itself, a more objective representation of reality. Thus, we must be careful not to conflate the subjectivity of photography with untruthfulness.

Fortunately, the truth of the South African Apartheid has not died with Peter Magubane. His work lives on to narrate the horrors of history. It is with Peter Magubane’s realist photographs that we can trace the trajectory of South Africa from Apartheid to the present day. After all, places like Orania were not manifested out of thin air.

Comments