‘Drop my body on the steps of the FDA’: how David Wojnarowicz fought back

While many of us are familiar with the AIDs epidemic, it’s easy for the millions of individual tragedies to dissolve into nothing more than impassive numbers and statistics. Since 1981, when cases were first reported, more than 84.2 million people were HIV infected and 40.1 million have died from AIDS-related illnesses. These statistics may highlight the scale of the epidemic, but they fail to capture the emotions of that time: terror, anxiety, grief, shame, and anger. Artists like David Wojnarowicz manage to translate personal experiences and feelings during the AIDs crisis into art pieces, making them permanent reminders of the epidemic history wants to forget.

While Keith Haring is the most recognised artist from the 1980s crisis, Wojnarowicz immortalises his emotions so articulately, in every possible form of media, that it’s impossible not to empathise. One of his most well-known works is ‘One Day This Kid’, which has a self-portrait of the artist as a prepubescent boy and contains a paragraph of text: “one day this kid will get larger… politicians will enact legislation against this kid… he will be subject to loss of home, civil rights, jobs and all conceivable freedoms”. Although Wojnarowicz produced plenty of pieces throughout his lifetime, his most iconic artwork embodies the main themes of his work, such as the loneliness that came with being an outsider to society, his anger at the American government for failing the queer population, and the unique tenderness of being a man who loves other men.

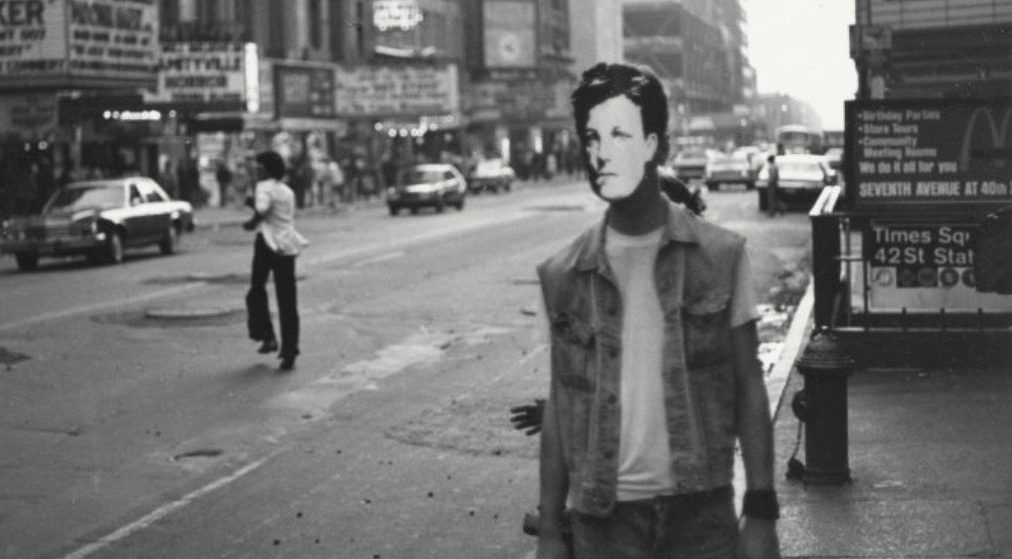

There’s a justifiable anger in Wojnarowicz’s art, as he spent his adult life fighting for AIDs to be officially recognised, for justice for the friends he lost to the disease, and for treatment to be provided by the powers-that-be. He was terrified, paranoid, and wrecked by grief — as a mysterious “cancer” began to claim whole communities, including his own — but more than anything, Wojnarowicz was angry. He raged against an unfair system that killed people like him. At times of political turmoil, modern activists have recirculated an image of the artist at a 1988 demonstration at the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) headquarter, wearing a jacket painted with a powerful message: ‘IF I DIE OF AIDS—FORGET BURIAL—JUST DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF THE FDA’. Wojnarowicz had been diagnosed with HIV the year before and would live with the disease for four years following the FDA protest. His death was marked by a memorial procession, in line with his belief that America should see the grief caused by AIDs, and lead by a banner that read ‘DAVID WOJNAROWICZ DIED OF AIDS DUE TO GOVERNMENT NEGLECT’. In life, Wojnarowicz understood the power of art as a “dismantling tool” to use against systematic oppression and, even in death, his work continues to be used by activists— unlike Haring’s iconic doodles, which have been stripped down and exploited by the fashion industry.

Wojnarowicz refuses to be silenced.

Too often, we learn how ‘unsanitary’ parts of history have been silenced and erased by those who hold the power to construct historical narratives. While it’s true that history is “written by the victors”, it’s also written by the survivors: the 40.1 million people dead from AIDs-related illnesses aren’t alive to combat how we remember this chapter of history, forced to rely on those who did survive the epidemic to tell their stories. But Wojnarowicz refuses to be silenced, even during the McCarthyist, ‘don’t ask don’t tell’ era of the 1980s, and has left permanent reminders of the suffering felt by queer, poor, and POC communities. Despite both historical and modern attempts to suppress his art for being inappropriate, his artwork has been well-archived and is still regularly shown in exhibitions today, with Wojnarowicz being recognised as one of the best artists from the AIDs crisis. The rawness of his emotions, combined with his direct political action, means he is remembered for his powerful, intertwined activism and artwork.

History wants us to forget the people that the government neglectedwic.

Although Wojnarowicz’s work focuses on the political, (including the ‘personal’ as the political), it’s the vulnerabilities of human experiences and emotions that keeps me coming back to him. Most of us know the basic facts of the AIDs crisis, but he creates empathetic portraits of the people living with the disease, with a focus on his close friends. These people aren’t just numbers: they’ve got childhoods, dreams, failed careers, bills to pay, vices, relationships, and fears. They’re people, no different from anyone else. History wants us to forget the people that the government neglected and, in the light of the Covid-19 pandemic, the people that are still being neglected today. The AIDs epidemic isn’t over.

In 2021, around 650,000 people died from AIDs-related illnesses worldwide, but we still talk about the epidemic as if it’s a chapter that we’ve closed the book on. So, when you’re looking at the work of artists like David Wojnarowicz (something I strongly recommend), it’s worth remembering that the AIDs crisis isn’t just a chunk of tragic history: we’re still living with this disease.

Comments