‘La Dolce Vita’: sublimating decadence

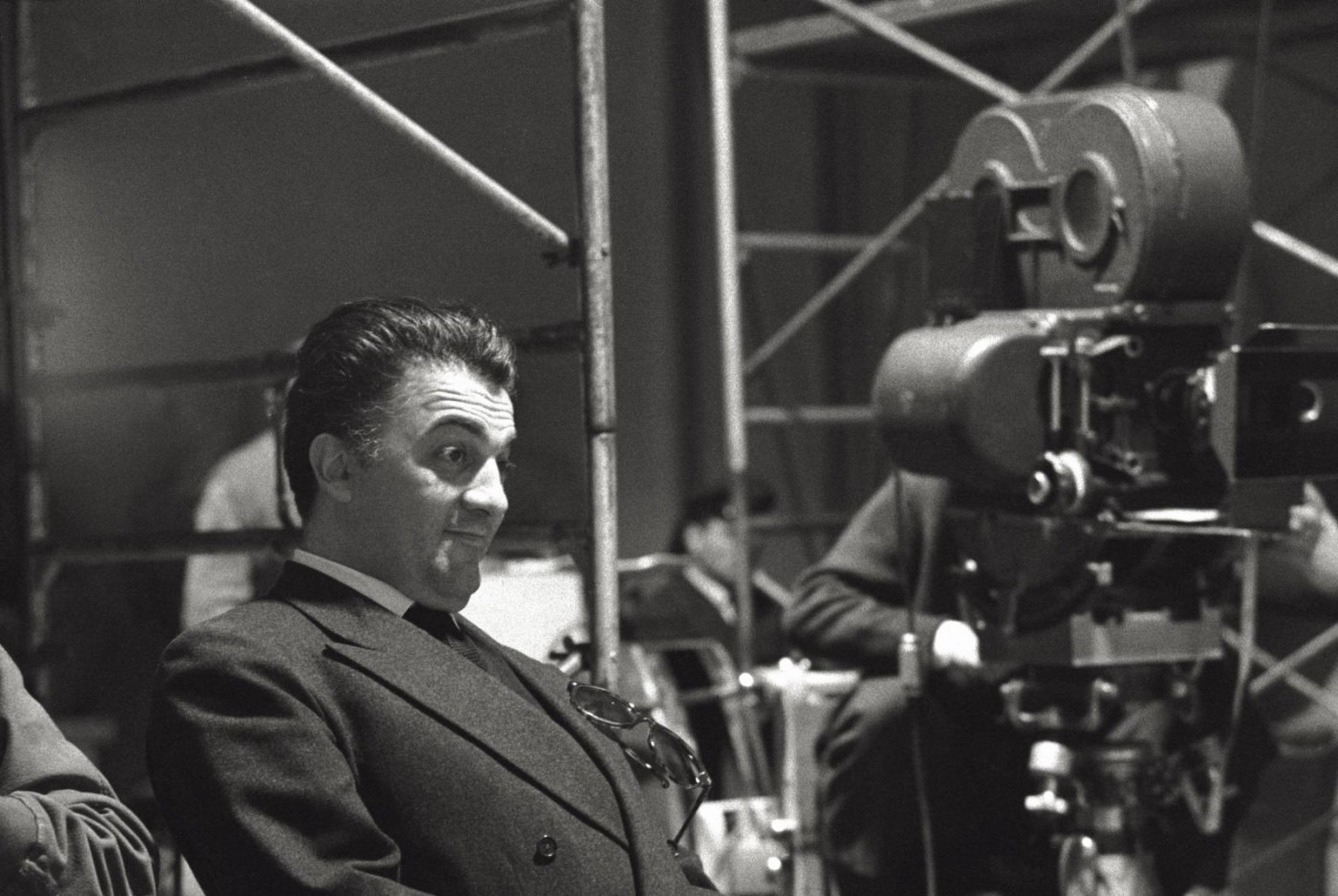

In 1993, Martin Scorsese paid tribute to the life and work of the then recently passed Federico Fellini, saying he “had something very special, a particular vision of the world that once started in a sense of poetical realism and as it developed, became more abstract in terms of its imagery but ultimately stylized.” He follows, underlining how “Felliniesque became a common word to describe something on the surface you can say bizarre but actually really like a painter’’. Scorsese’s remark on Fellini’s work particularly resonates with his masterpiece, La Dolce Vita – a film fresco-composed of seven sequences, with a symmetric structure, all intimately linked to each other.

La Dolce Vita cannot be detached from its historical and political context. Released in 1960, Italy was experiencing a prolonged period of strong economic growth: The Italian Economic Miracle (1958-1963). It was a pivotal time between the post-war period and the beginning of a new consumerist society. Consumption grew whilst the hardships of war were becoming increasingly distant. Meanwhile, Rome was becoming the centre for the display of the bourgeois. The global reach of Italy, and of its capital city, reached its peak with the 1960 Rome Olympics which marked Italy’s return to the international stage. Meanwhile, the Cinecìtta film studios turn Rome into a second Hollywood. Fellini tried to capture the essence and the atmosphere of these ostensibly joyful times, specifically through his exploration of the character Marcello Rubini (Marcello Mastroianni), a tabloid journalist in Rome in the late 1950s.

Fellini’s aim is as much to criticise the depraved bourgeoisie as to show the failings of contemporary society and the dark side of hedonism which makes people more prone to nihilism

Through Marcello’s peregrinations, Fellini depicts Italy’s superficial and decadent high society. The film shows us the idle and debauched Roman bourgeoisie trying to fill their meaningless existence. Instant pleasures take on the appearance of temporary escapes; the characters indulge in sin without batting an eyelid. Music, alcohol, sex, and parties are the mainstays of the lifestyle that makes them suffer. Yet, they nonetheless choose to indulge all-the-more. Perhaps most strikingly, the stories are all drawn from real events; Fellini explains: “My collaborators and I only had to read the newspapers to find exciting material.”

Fellini’s aim is as much to criticise the depraved bourgeoisie as to show the failings of contemporary society and the dark side of hedonism which makes people more prone to nihilism. Paradoxically, at a time when life is sweet, the banality of existence, the difficulty of being happy and the meaninglessness of suffering, are coldly revealed to us. Marcello’s friend Steiner (Alain Cuny) is the perfect representative of the man who seemingly has everything to be happy for – success, family, stability. But he still sinks into nihilism. He reveals his own doubts and his fear of chaos, held in check by a fragile serenity. He finds an immutable and sure truth only in art and aesthetics.

One of the film’s central themes is the role of the media, which the Italian director points out. Now thirsty for gossip and sensationalism, the celebrity press draws the public’s attention to trivial, ridiculous, and unhealthy subjects. Worse, the new media and paparazzi play on the population’s baser instincts and encourage collective hysteria, as in the case of the religious miracle which becomes a gigantic open-air TV set. It was Fellini who coined the term paparazzi. Indeed, Marcello is often accompanied by a young photographer called Coriolano Paparazzo, the director having contracted the words pappataci (little mosquitoes from the Po Valley) and razzi (flashes of light) to find the name. The rise of this type of press heralded the emergence of a society of spectacle and sensationalism, devoid of any reflection or complex thought.

The three hours of viewing are punctuated by a scene that reflects the film, full of meaning and aesthetics

An inescapable phenomenon in a sick high society, the sacred is disappearing, swept away by a contemporary world that is too hedonistic to think bigger and further. Fellini thus accumulates different incarnations of the spiritual in an apparently trivial world. There are many examples of religion being flouted. In the opening scene of the film, a statue of Christ is transported by helicopter, slaloming between housing estates and passing over football pitches, desecrating a now purely mechanical ascent to heaven. At the end of the film, a friend of Marcello’s celebrates her divorce with a drunken party which she concludes with a striptease. Earlier, the group of friends coming back from their party at dawn and meet on the way some relatives going to mass. The idiom ‘walk of shame’ has never been so fitting.

In this singular world that surrounds him and of which he is a part, Marcello is searching for himself. He is searching for meaning, depth, inspiration – all quests that his job, his social environment, and his pace of life are unable to offer him. He melancholically confesses that he would have liked to be a writer. He is now the victim of these hysterical parties which always end in a violent return to reality. Disillusionment and resignation overtake him when his friend Steiner, the only inspiring figure in his eyes, dies. While voices were presented to him, they eventually proved to be hopeless, and he ends up alone like any Fellini hero.

The three hours of viewing are punctuated by a scene that reflects the film, full of meaning and aesthetics. The group of friends go to the beach at dawn after yet another night of drinking. They pull a sea beast out of the water, dying, but still able to judge them. Marcello sees a young innocent girl, symbolic of the real sweet life but with whom he is unable to communicate.

Comments (1)

Bravissimo Hector