The math ain’t mathing – maths till 18’s adverse effects on student self-image

In a speech made on the 4th of January this year, our Prime Minister Rishi Sunak set out plans to make some form of maths education compulsory until the age of 18, to help young people prepare for a world where “data is everywhere”. As it stands, approximately half of 16-19-year-olds study any maths at all. As a postgraduate sociology student, I was under the impression that I had to force myself to take quantitative methods modules in my undergrad so I could maximise my employability and avoid being condemned to a life of teaching. The undervaluing of the humanities had really gotten to me throughout school, and I was constantly conflicted as to what the point of my degree was, and at times, allowed my lack of affinity for maths to bleed into how I felt about my intelligence more generally.

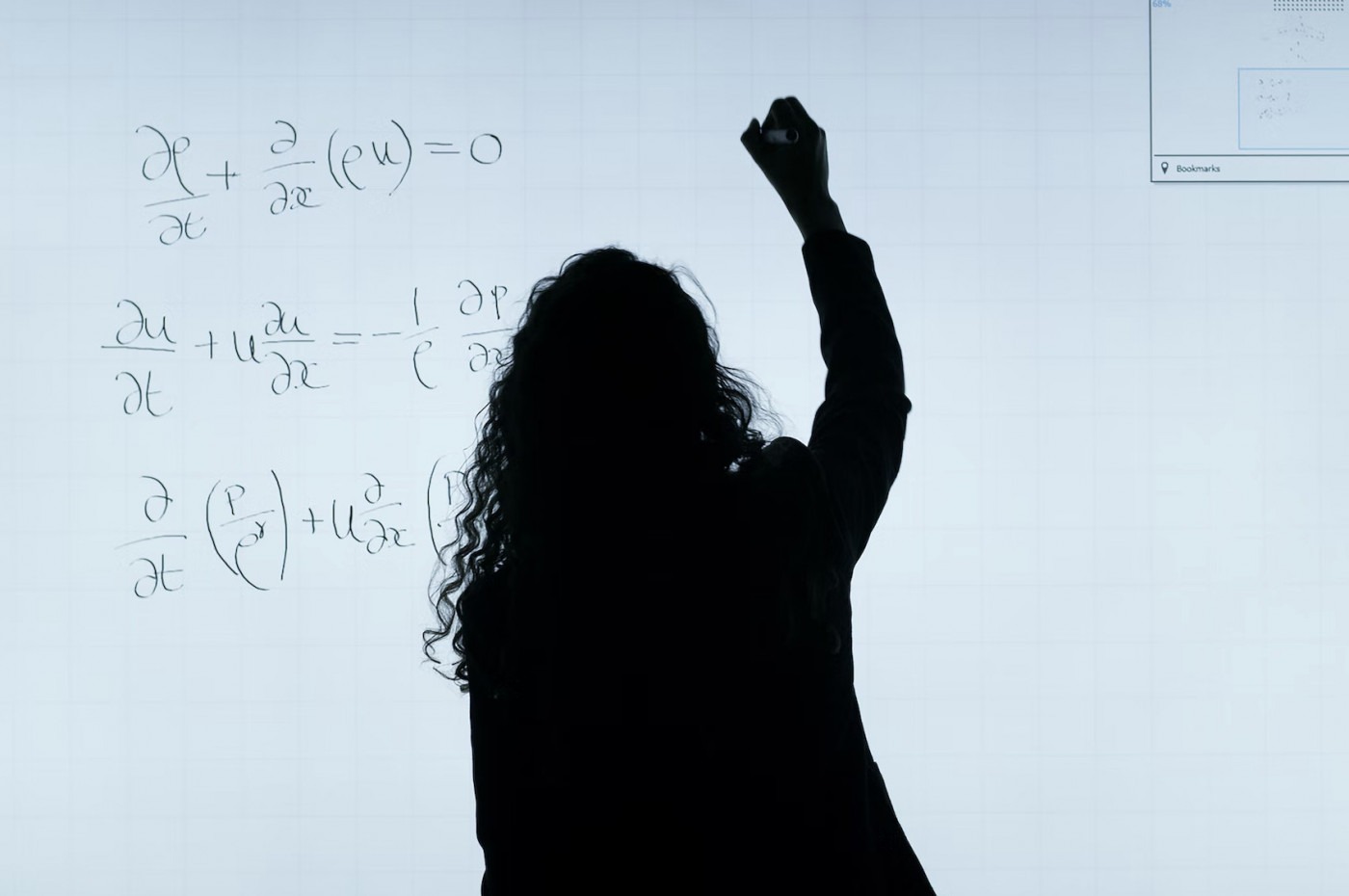

Mathematician Hannah Fry points out that in the last 20 years, the workforce has changed significantly as the world has become increasingly data-driven. While many people could once enjoy successful careers without even having to engage with maths, this is arguably no longer the case. As almost every employment sector now relies on data in some capacity, there is maybe some rationale behind Sunak’s proposal, but for those whose academic strengths lie in other areas, how will being forced to engage with maths until 18 negatively impact the self-image of students?

Putting so much emphasis on maths over other subjects at school will only pigeonhole students into a future they weren’t built for.

There is much discourse around the importance of self-esteem in schools. The self-esteem of children will not only motivate them to learn, but also teach them to take risks and bounce back from failure. While this names schooling as a primary site of self-esteem building, Julian Baggani writes that many pupils from state schools lack confidence, primarily because academic attainment is prioritised over cultivating a sense of self-esteem more generally. As someone who was overjoyed by a C in GCSE maths, who is now a postgraduate student at Warwick, being forced to study maths till 18 would’ve warped my self-image even more than secondary school already had. Take those of us who study humanities at university for example: clearly, none of us are dumb by any means, yet we are often mocked by our STEM peers for our unemployability and lack of affinity for maths. Speaking more directly to the hierarchy of STEM and humanities, where does this negative attitude towards the humanities stem from?

Kristen Shi writes that the teasing humanities students are subject to points to a “much more insidious bias that persists long after graduation”, having huge effects on the way in which we make value judgements on people, and importantly, how we make these judgements on ourselves. Though the value of STEM degrees is undoubtedly high, as evidenced by achievements in sectors like tech and medicine, but we cannot allow this valuation to come at a cost to the self-confidence of those whos abilities lie ensewhere.

Though the world is more ‘data-driven’, Valerie Strauss emphasises the importance of humanities to open “a window into a new culture, a new worldview”. In the data-driven world we live in, understanding how to generate data is one thing, but an understanding of why is all the more important. Putting so much emphasis on maths over other subjects at school will only pigeonhole students into a future they weren’t built for, continually hacking away at their self-confidence in the process.

STEM would be nothing without the arts, and they should be valued as such.

School around the time of GCSEs and A-Levels is already highly stressful, with 86% of students noticing a decrease in self-esteem, and 76% seeing an increase in depression. Clearly, schools are not cultivating the self-esteem and problem-solving skills that are so vital for young people at that time in their lives. I know that in my experience, my GCSEs were extremely stressful for me- affecting my attendance and both my physical and mental health. Upon dropping maths and science at A level, I immediately felt more in control of my well-being, and felt I could properly cultivate my own sense of self-worth- a skill so vital as a person transitions into adulthood.

So when it comes to maths till 18, its potential negative effects on students’ self-confidence. If the opposite were the case, that students would be forced to learn English or History till 18, there would no doubt be outrage. In a world so driven by data, we are under the impression that generating data and interpreting numbers are all we need to thrive, but with this evolution, data has been removed from context and weaponised. The arts are important! It is the articles you read, and the activism that betters our world. Ultimately, STEM would be nothing without the arts, and they should be valued as such, so all students feel as though they are equally part of something important.

Comments