The halo effect on trial: Luigi Mangione and Gen Z’s obsession with looks

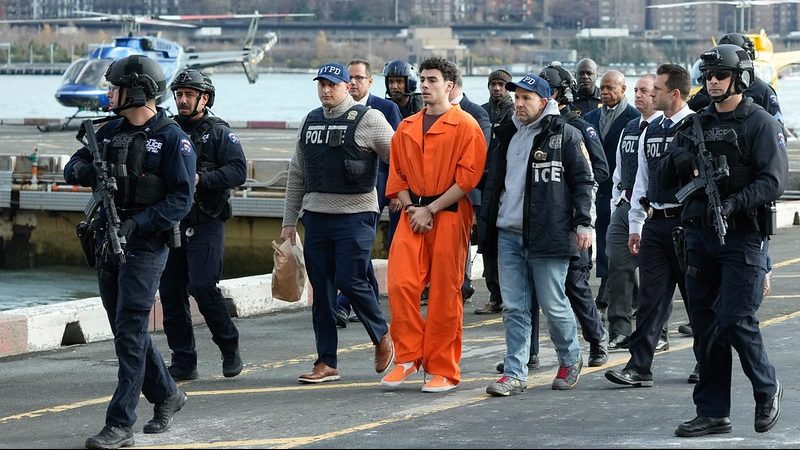

When Luigi Mangione’s chiselled jawline first graced the collective consciousness of the internet, it wasn’t in a Calvin Klein or luxury fragrance advert, but on grainy security footage accompanied by an announcement from the NYPD (New York City Police Department). The Ivy League-educated 26-year-old was arrested for the murder of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson, a crime described as an act of terrorism. And yet, rather than universal condemnation, w hat followed was a tsunami of TikToks thirsting after Mangione, Instagram accounts dedicated to him, and even Luigi Mangione look-alike contests held at universities across the US.

The case has become a masterclass in a cognitive bias known as the halo effect, where one positive trait which in this case, physical attractiveness, casts an irrational glow over everything else. What should be a sober discussion about justice has become a chaotic blend of fan fiction, political commentary and ironic memes. The legal trial might take place in a courtroom, but the cultural battle is playing out on social media where the jury of public opinion seems to be far more interested in Mangione’s smile than in the damning evidence against him.

On account of his symmetrical features and brooding mugshot, Mangione has been depicted as a misunderstood anti-hero by way of the halo effect. This bias reveals a deeply ingrained societal flaw: we struggle to hold attractive people accountable.

The halo effect, which was first recognised by psychologist Edward Thorndike in 1920, describes the way in which physical attractiveness can skew our perceptions and lead us to praise someone based only on appearance for unrelated positive attributes like kindness, intelligence, or moral integrity. Studies consistently show that attractive people are more likely to receive favourable treatment in job interviews, academic assessments and most critically, in courtrooms. Jurors are less likely to convict attractive defendants and when they do, are more inclined to hand down lighter sentences. On account of his symmetrical features and brooding mugshot, Mangione has been depicted as a misunderstood anti-hero by way of the halo effect. This bias reveals a deeply ingrained societal flaw: we struggle to hold attractive people accountable.

If the halo effect is the bias, then social media is the megaphone. Social media platforms like TikTok, Instagram and Twitter are optimised for virality whilst beauty has always been one of the most valuable currencies, meaning that Mangione’s sharp cheekbones and icy blue stare make him algorithmic gold.

On TikTok, videos featuring Mangione’s face garnered millions of views while Instagram accounts popped up overnight, dedicated to posting curated collages of his images with romantic or rebellious captions. Users debated his motives, speculated about his backstory and expressed everything from admiration to infatuation. Some even dismissed the gravity of his alleged crime, posting comments such as, ‘Who cares if he did it! Is he single?’ under his images.

This phenomenon isn’t new. Social media has been turning criminals into viral sensations for years. Jeremy Meeks, who was convicted on grand theft and weapons charges, leveraged his viral mugshot into a successful modelling career with many famously dubbing him the ‘Hot Felon’. However, due to online users reinterpreting Mangione’s crime, the targeted murder of a well-known public figure, as a symbolic act of political defiance, his case assumes a more troubling dimension. The narrative surrounding Mangione resonates deeply with widespread frustrations about systemic inequality, allowing his alleged actions to be framed as a statement rather than a crime. Mangione’s alleged crime targeted one of America’s most controversial institutions: the healthcare system. Psychologist Dr. Elena Touroni explains that social media amplifies these emotional narratives as people are drawn to symbols of rebellion, which is exactly what Mangione has become- a flawed hero for a generation tired of systemic failures. It is essentially irrelevant whether Mangione aimed for his actions to be interpreted in this manner or not as irrespective of this, the internet has determined that he is the contemporary Robin Hood, albeit one with better abs. Nonetheless, this digital romanticisation comes at a cost as victims are reduced to footnotes, moral complexities are erased and the conversation shifts from accountability to aesthetic appeal.

Though what sets Mangione’s case apart from the others is the way in which the narrative has been supercharged by the power of social media. Unlike Bundy or the Menendez brothers, Mangione exists in a hyperconnected world where content spreads globally in seconds.

The fascination with attractive criminals isn’t unique to Luigi Mangione. There are numerous examples throughout history of criminals whose appearance made them famous. The most notorious example is Ted Bundy, whose charm and attractiveness were key factors in his ability to entice victims in the 1970s. Women flocked to his trial even after his arrest, some proposing marriage and others writing him love letters. Even today, Bundy’s reputation as a ‘charismatic’ monster is still maintained by documentaries and movies, consequently undermining the severity of his atrocities. Similarly, the Menendez brothers, who were convicted of murdering their wealthy parents, became teenage heartthrobs during their trial in the early 1990s. Fans attended court proceedings, sent them gifts and wrote them letters with both brothers eventually marrying women they met while incarcerated.

Though what sets Mangione’s case apart from the others is the way in which the narrative has been supercharged by the power of social media. Unlike Bundy or the Menendez brothers, Mangione exists in a hyperconnected world where content spreads globally in seconds. The halo effect is directly fuelled by Mangione’s well-curated online persona, including fashionable attire, gym selfies and carefully chosen Spotify playlists.

The distinction between hero and villain has become blurred on account of this cultural obsession with the archetype of the alluring, morally dubious antihero. But why? A combination of psychological bias, media influence and societal disillusionment may be the cause of our fascination with these figures. Our preconceived notions of what the appearance of a “villain” should be is challenged by attractive antiheroes, causing cognitive dissonance which we attempt to overcome by giving them redeeming traits. Mangione’s case demonstrates the profound impact implicit biases have on how we perceive danger and guilt. This is partly due to a natural desire to comprehend and humanise criminals. This tendency is frequently linked to the saviour complex, in which people persuade themselves that they can change or even save the criminal. These narratives are heightened through the use of social media which distorts our perception of reality by transforming real crimes into fictional tales of beauty, rebellion and tragedy. Though despite their emotional appeal, these narratives rarely reflect reality.

There is an ethical minefield at the crossroads of true crime, social media, and the halo effect. What happens to justice when we make alleged criminals famous on the internet?

The glorification of Luigi Mangione has already begun to shape public opinion, and it could consequently influence the outcome of his trial. Jury selection in high-profile cases is already a delicate process, but the Mangione phenomenon has raised new concerns. How do you ensure a fair trial when half the jury pool might have seen TikToks declaring him a misunderstood hero? In addition, the focus on Mangione’s physical appearance sidelines the victim, Brian Thompson, whose life was abruptly and violently cut short. The memes and viral thirst traps which dominate the story make his family’s grief, the circumstances of his death, and the crime’s effects on society seem like footnotes. In today’s world of clickbait headlines and viral content, sensationalism often eclipses substance. The Luigi Mangione case raises important ethical concerns about how we consume, share and respond to crime in the digital age, demonstrating how easily digital culture can warp our understanding of justice, trivialise tragedy and distort reality.

Mangione’s trial will conclude in a courtroom. But the cultural phenomenon he represents, with our obsession with beauty, our love of rebellion and our willingness to turn tragedy into content, will linger far beyond the final gavel.

The Luigi Mangione case is a trial of the audience as a whole, not just of one individual. Can we distinguish evidence from aesthetics, fact from fiction? Do we want to live in a society where someone can literally become famous for murder as long as they look good doing it?

Mangione’s trial will conclude in a courtroom. But the cultural phenomenon he represents, with our obsession with beauty, our love of rebellion and our willingness to turn tragedy into content, will linger far beyond the final gavel.

If the Luigi Mangione saga teaches us anything, it’s this: We might be infatuated with a killer, but the real crime is how willingly we let ourselves fall for the fantasy.

Comments (2)

There is a reason why there are institutions and professionals that seek and make justice, ask them, because they are doing anything, just not what they are built and exist for. I raise a bigger concern for you: How do you ensure a fair trial when media outlets already paint him as guilty when no trial is made and a citizen has the presumption of innocence, when his constitutional rights are violated, when charges are overloaded and unprecedented, when the Mayor is all prepped up to talk about the case as if it’s closed, when Luigi is treated differently from other inmates, when the judge is biased and speaks in threatening tones, when evidence is not shared with the defendant’s lawyers but it is with studios to make documentaries, when he is shackled to the bone and when social media content expressing sympathy and support for Luigi gets censored ?

I raise a bigger question: Are journalists capable to write facts rather than garbage reporting based on their feelings ? Cause if “Mangione’s trial will conclude in a courtroom”, then why you write this piece of shit with the presumption of guilt for him ?

Wow! You just proved the author’s point!

And as for guilty with no trial: what about Brian Thompson? What trial did he have when he was killed.

But, you have the right idea: Stick Mangione in gen pop.

Will you also idolise whoever kills him then?