Hungering for more: are we addicted to food?

Although we’ve all heard about the ‘obesity crisis’ in the UK, which affects an estimated 25.3% of adults aged 18 and over, our collective relationship with food is the real crisis in the 21st century. While most of us are familiar with anorexia and bulimia, there are other types of disordered eating that may go unnoticed: as many as 20% of people may have a food addiction or exhibit addiction-like eating behaviour. It isn’t so far-fetched to consider that food can be an addictive substance: just like drug use, eating can result in the release of dopamine in mesolimbic regions of the brain. Food and drugs can also cause similar patterns of brain activation in response to cues. With food providing a source of stability and comfort in an increasingly uncertain world, could addiction become a major problem for our generation?

Like any other substance, it’s easy for humans to become addicted to food — and it may be more common than previously thought. Neurological studies have found evidence that food triggers the same pleasure and reward areas of the brain as highly addictive drugs, such as heroin and cocaine. The same study found similar patterns of neural activation in addictive-like eating behaviour to those implicated in substance dependence. Additionally, there was elevated activation in reward circuitry in response to food cues and reduced activation of inhibitory regions in response to food intake, making people more inclined to ‘binge’ on food. Highly palatable foods — such as those rich in sugar, fat, and salt — are even more likely to trigger addictive behaviours.

29% of Warwick students surveyed reported that they binged on food once a month

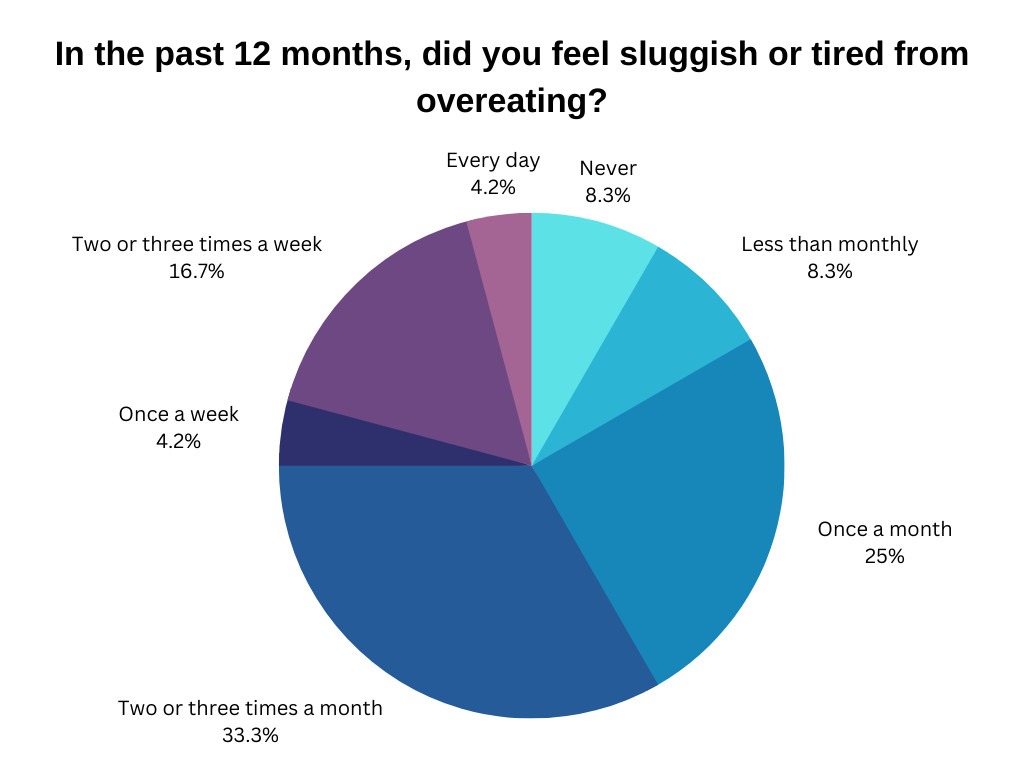

Addiction to food can result in overeating, as the reward signals may override the feelings of fullness and satisfaction, meaning that people keep eating even if they’re no longer hungry. It can also result in a ‘tolerance’ to food, causing people to eat more but feel even less satisfied. Of those surveyed, 58% of Warwick students reported that they felt tired or sluggish multiple times a month as a result of overeating, which is also a symptom of food addiction.

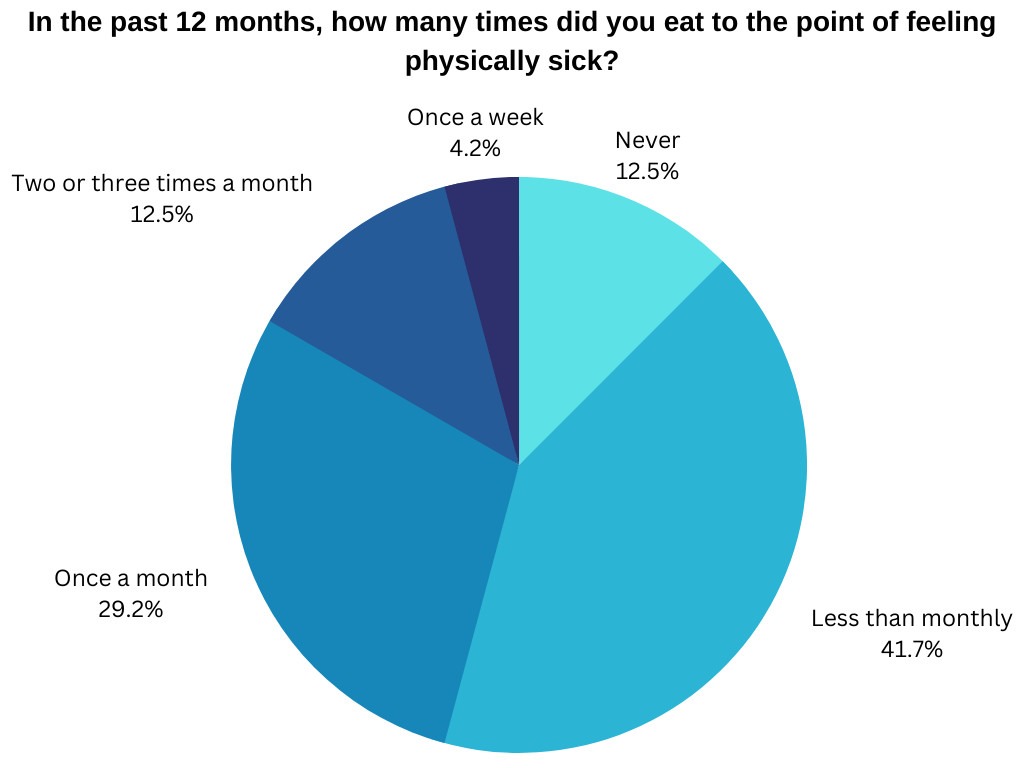

This neurological evidence could explain why Binge Eating Disorder (BED) is so common, affecting three times more people than anorexia and bulimia combined. Binge eating episodes, where someone eats ‘too much’ in a single sitting and their eating feels out of control, make sense when comparing neural responses to food and drugs. However, eating like this isn’t limited to those with BED: 29% of Warwick students surveyed reported that they binged on food once a month, with 16% doing so multiple times a month, until they felt physically sick.

Attending university has been proven to be a factor in altering food and eating behaviour

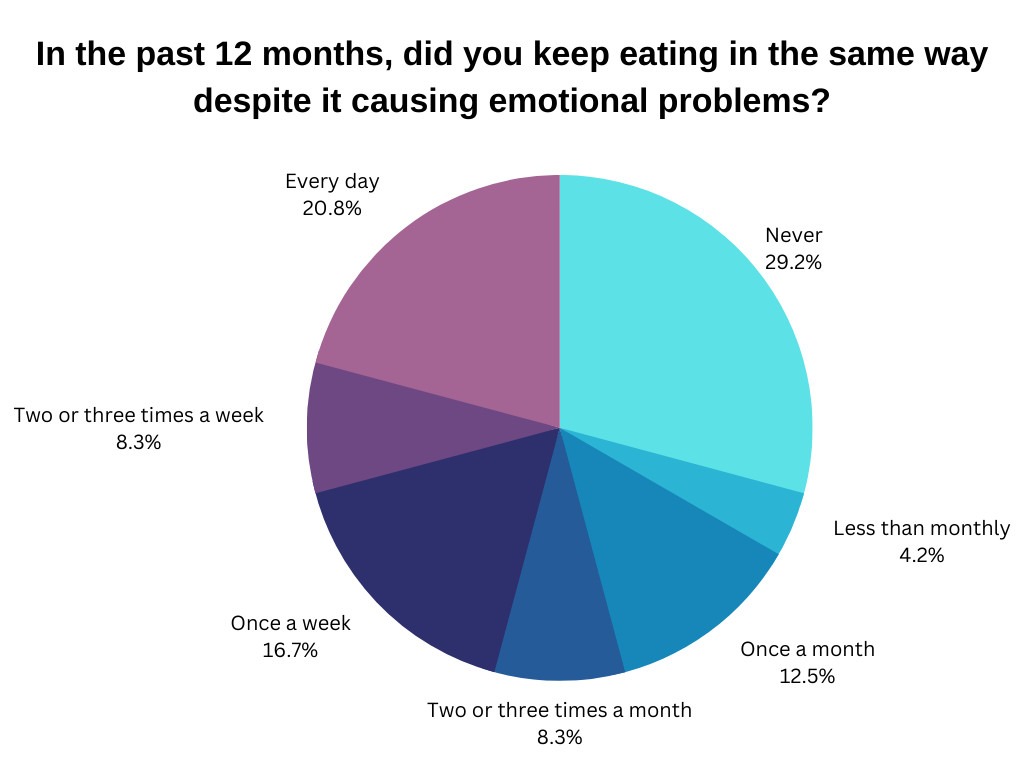

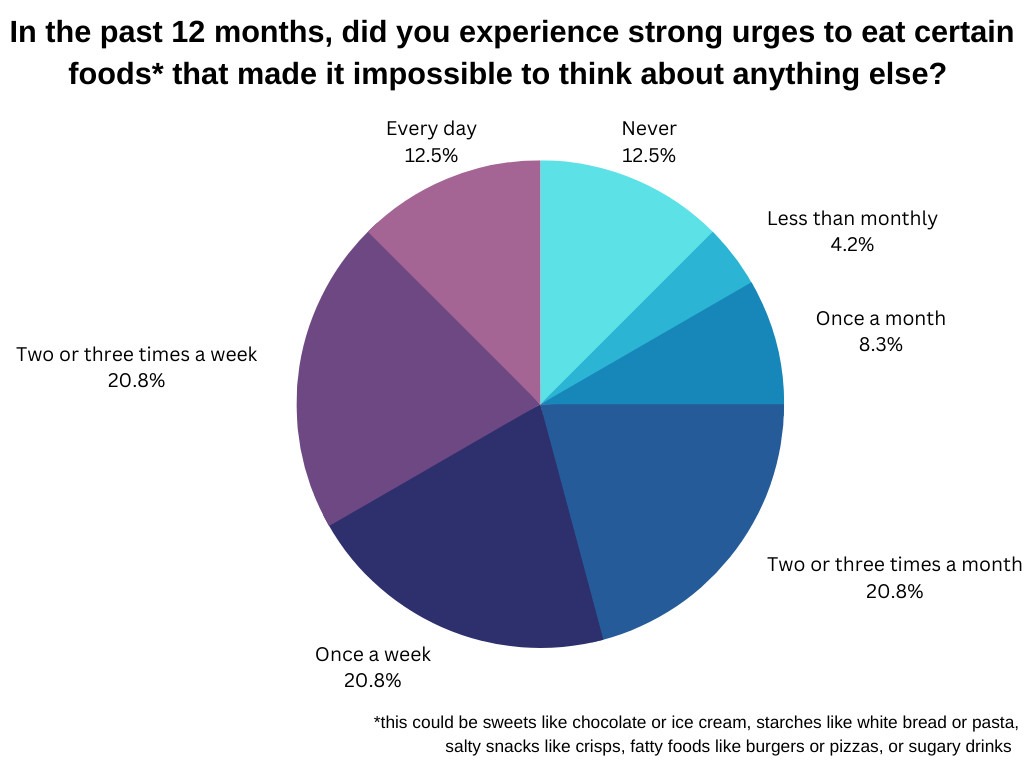

Like with all addictions, people with food problems will continue to eat despite negative consequences, such as weight gain or damaged relationships. They spend excessive amounts of time with food, overeat, and anticipate the emotional effects of food. For example, once a week or more, 54% of Warwick students experienced such strong urges to eat certain foods (such as sweets, starches, or fatty foods) that they made it impossible to think about anything else. The addiction can be even more difficult to overcome than addiction to drugs or alcohol because, unlike with those substances, people can’t avoid eating food or being exposed to food cues. In the UK, there has been an increase in the availability of highly palatable and fatty foods over recent decades, which is leading to a rise in food addiction and could explain why our relationship with food is changing.

Attending university has been proven to be a factor in altering food and eating behaviour, with students commonly switching from eating soup, pasta, and salads to snacking on confectionary and crisps. Studies have also associated increases in alcohol and sugar intake with the transition to university, resulting in the commonly held belief that most students will gain weight during their first year of study — in the US, this is referred to as the ‘freshman 15’. As university has a major impact on food consumption, The Boar was interested to research whether it resulted in addictive-like eating behaviour, using the Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS).

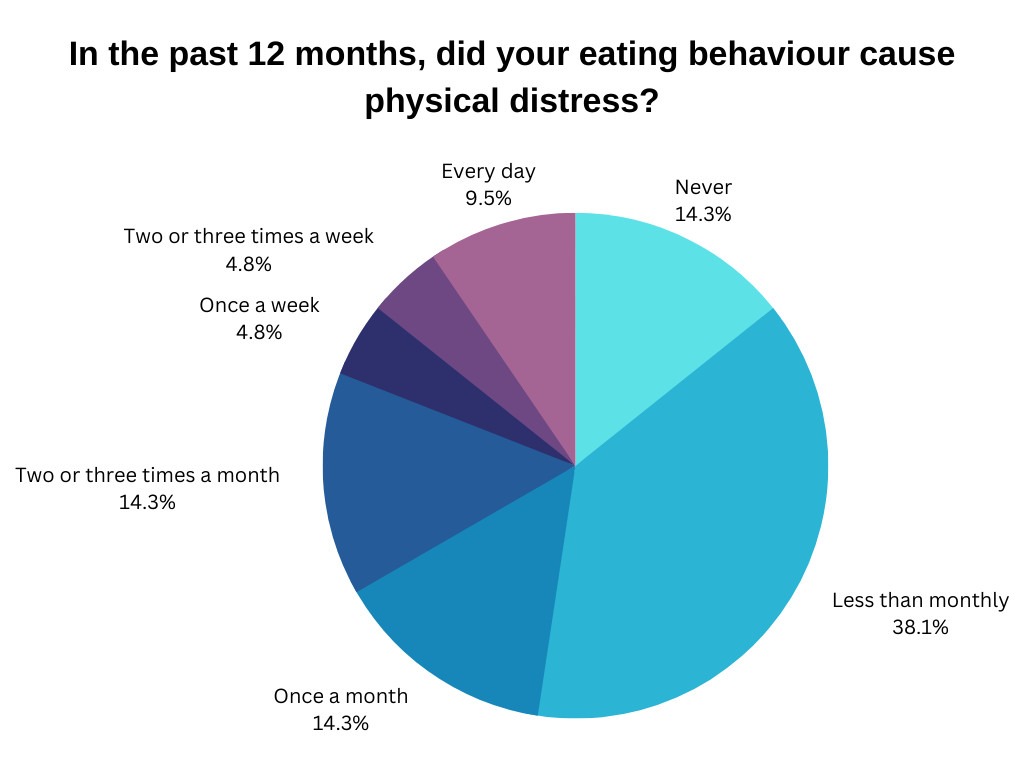

Overall, most people reported experiencing some symptoms of food addiction, even though they weren’t severe enough to impact their life on a daily basis. More than half of students surveyed reported that food and eating had caused significant problems in their life during the last year. Additionally, 41% had experienced physical distress once a month (or more) due to eating problems and 13% did so several times a week. Although disordered eating is on the rise, this is still higher than the UK average, which is 6.4% of adults according to the NHS.

It’s clear that the UK has a deeply unhealthy relationship with food and students are disproportionately affected more than the average adult. However, the focus on the ‘obesity crisis’ may be misplaced, as eating problems don’t start and end with a person’s weight. Instead, there needs to be more information shared about food addiction — which seems to affect an average of between 8 to 16% of students at the University of Warwick — and how to form a healthier relationship with food. If universities don’t make an effort to combat the ‘eating crisis’ of the 21st century, it could have disastrous consequences for our generation.

The full results of the survey conducted by The Boar into the eating habits of students at the University of Warwick are shown below.

Comments