Truss’ energy plans alone can’t avert a recession

A new era of crisis is enveloping markets, governments, and central banks of advanced economies the world over. News broke in August that the Bank of England is forecasting that the UK will enter a recession in the final quarter of 2022 which would continue for the rest of 2023, thereby tolling the beginning of the longest recession to hit Britain since the global financial crisis of 2008. The depth of this recession will be determined by what the new Prime Minister Liz Truss and Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng decide to put into action before Christmas trees go up in homes across the country.

Although the jury is still out on ‘Trussonomics’, what is becoming evidently clear is that Truss’ energy plans alone won’t do nearly enough to avoid a harsh recession. The new Prime Minister announced that average energy bills will be capped at £2,500 until the end of 2023, substantially reducing the existing Ofgem, the UK’s energy regulator, price cap of £3,549. While certainly of great assistance to households when compared to the previous price cap, at over £100 billion in cost it is a major intervention.

While focusing on an energy price cap is important, it is not the panacea that Truss may be praying it to be

Racking up debt, combined with a predicted peak of inflation at 13.3% and the highest interest rate hike in 27 years, now standing at 1.75% (compared to 0.1% in December 2021) are dangerous injuries for an economist’s intensive care patient. An apt doctor in this analogy should see that treating the major wound, energy prices, with ibuprofen, will not cure the patient in full.

While focusing on an energy price cap is important, it is not the panacea that Truss may be praying it to be. The seeds of this upcoming recession were likely sewn years ago; a compounded result of economic catastrophes from Brexit to the Covid-19 pandemic and all the instability that accompanied both. The primary reason why a simple energy price cap cannot soften the wider recession at hand is the relationship between energy prices and the goods and services in the nominal price index.

Perhaps a continuous obligation to maintain a 2% target in such volatile economic seas is more dangerous than the alternative

As outlined by the Financial Times, if energy prices make up about 10% of the nominal price index of an economy, such as in the EU where they account for 9.5%, a tripling of energy price rises would have to be followed by a 20% aggregate drop in prices in the rest of the index. Only in this way, would a central bank be able to offset inflationary pressures to stay within a 2% mandate. And no Central Bank in a free-market economy could fathom such a massive drop in other prices in the immediate term.

This may serve as a good reason to reconsider the mandate of the Bank of England on the whole, as perhaps a continuous obligation to maintain a 2% target in such volatile economic seas is more dangerous than the alternative. Of course, this has been something that the new Chancellor has sought to exclude as a possibility. In his first meeting in his new role, he sought to calm Andrew Bailey, the Governor of the Bank of England, that the Government does not intend to meddle with the independence of the Bank set in stone by Gordon Brown in his first days as Chancellor in 1997.

The main priority here will be to untangle the gordian knot of the Northern Ireland Protocol and take proactive steps to restore trade balances with the EU

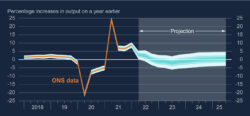

The war in Ukraine, which has turned into a war of attrition, dragging out for over seven months at a massive humanitarian and financial cost, has brought about the latest contributing factor to the forecasted drop in economic output in the UK. But, as the Bank of England’s own projections show, there is a high level of uncertainty about how much economic output may drop until the end of 2023:

This, oddly enough, can serve as a dim point of hope in the economic outlook and provide political impetus; it gives the government valuable space to implement policies that will prioritise staying the drop of the UK’s economic output. The main priority here will be to untangle the gordian knot of the Northern Ireland Protocol and take proactive steps to restore trade balances with the EU.

The pressing situation of the coming winter calls for urgent action to aid British output as quickly as possible

Although politically unlikely it is crucial for the economy that Liz Truss softens her stance on the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill. It was proposed to the House of Commons by her as Foreign Secretary in June of this year and led the European Commission to take legal action against the UK for breaches of international law. As the House of Lords considers the bill, it is essential that amendments focus on conflict resolution – for in the coming months the last thing that the UK needs is further tensions with its largest trading partner when trade opportunities seem ever the rarer.

The growing concern shared amongst those sceptical of supply-side macroeconomic policies touted by Ms Truss in her leadership campaign is that if they do work, these policies’ benefits are felt in the long run. And as Keynes famously wrote: “in the long run we are all dead”.

The pressing situation of the coming winter calls for urgent action to aid British output as quickly as possible. This may be a gargantuan task, but it is Liz Truss and the Conservative’s golden opportunity to secure political success in the future.

Comments