What makes a film beautiful? Truth, lies and a world of pure imagination

In the age of social media, the question of ‘what makes a film beautiful?’ has become more scrutinised than ever before. Still images from films are taken and plastered all over the internet, with accounts such as @oneperfectshot (which I highly recommend following) curating a modern pantheon of cinematic excellence. The trouble is that to pinpoint exactly what makes a particular film ‘beautiful’ is no easy feat. Art is subjective. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. All of this seems to suggest that to accurately describe the exact source of a film’s ‘beauty’ is all-but impossible.

In attempting to answer this question from a technical standpoint, one would likely first consider cinematography. While early films would solely rely on camera placement, cinematography has evolved to a point at which a multitude of factors, such as colour, lighting, composition and focus, must be considered when structuring every shot. Only when all of these are combined can a specific shot stand out as beautiful, poignant and memorable. Ultimately, cinematography is the language of the cinema: it is how the cinematographer, director, actors and crew communicate the meaning of the scene to an audience.

Ultimately, cinematography is the language of the cinema

Yet there is no single way to do this. For instance, Roger Deakins, cinematographer on such films as Blade Runner 2049, Prisoners, and No Country for Old Men makes sure to avoid anamorphic lenses, holding a distinct preference for bold and striking colour palates with natural and practical lighting. The latter point is shared by many cinematographers, including Rachel Morrison, who was nominated for her first academy award for her work on Mudbound. In fact, Morrison goes even further, taking inspiration from her docu-filmmaking days to create a rugged aesthetic for her films. However, on the opposite end of the spectrum are Robert Richardson, a cinematographer boasting three consecutive Oscar wins, and Robert Elswit, frequent collaborator of Paul Thomas Anderson. Both of these fiercely revered cinematographers tend to utilise dramatic, top-down ‘Hollywood lighting’ to tell their stories, diverging away from realism and transporting us into a fantasy.

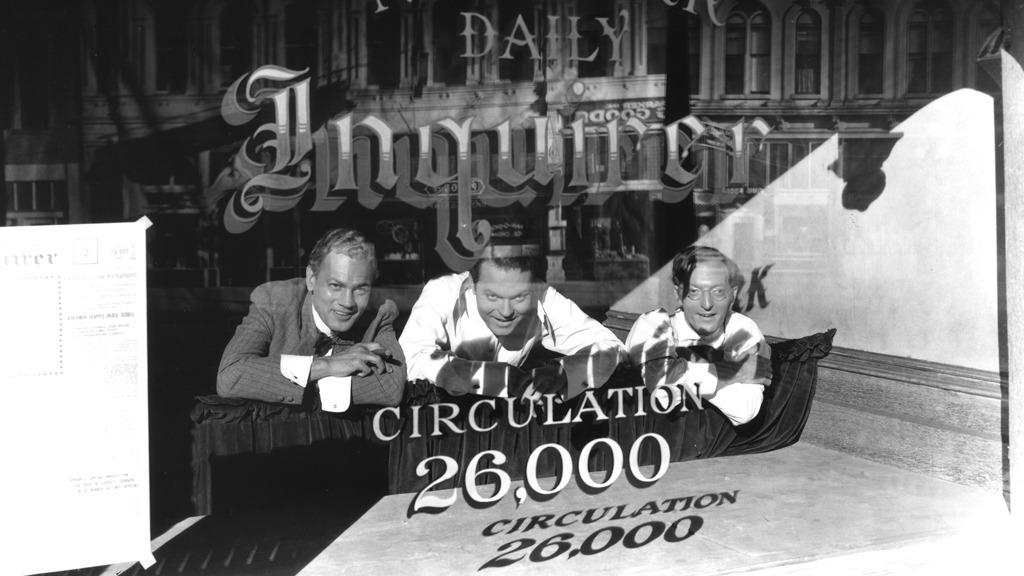

As demonstrated by these vastly distinct, yet equally fascinating, styles, beauty in film has always transcended exact science. In a 1960 interview promoting Citizen Kane, Orson Welles believed that it was the purpose of any filmmaker to ‘do anything with a camera that the eye could do, or that the imagination could do’. Indeed, Citizen Kane overcame a number of limitations present in the industry at that time, pioneering the use of low-angled shots and tracking shots after Welles encouraged cinematographer Gregg Toland to continue experimenting as he had done on previous endeavours.

Preceding Orson Welles was Dziga Vertov who, in 1929, released his little-known masterpiece Man with a Movie Camera, which was recently voted the greatest documentary in history in a Sight & Sound poll. The film pioneered a number of cinematic techniques, such as dissolves, multiple exposures, slow motion and other illusions. In this film, it is not the actors who are the stars of the show, but the camera itself. Man with a Movie Camera was a celebration of everything that cinema is and everything that cinema could achieve.

Man with a Movie Camera was a celebration of everything that cinema is and everything that cinema could achieve

In creating this film, Vertov goes a step further than Welles. His belief was that the camera was not only a tool to realise the imagination, but to overcome the limitations of human vision, dictating that the camera had the power to make ‘the invisible visible, the unclear clear, the hidden manifest, the disguised overt’. In saying as much, Vertov implies the existence of an untapped world beyond our collective imagination, only accessible to the naked eye through the lens of the filmmaker’s camera and the expression of the filmmaker’s imagination. As such, Vertov seems to suggest that the beauty of film comes from the journey that one is able to take the audience on, ultimately concluding with the revelation of ultimate truth.

Yet while Vertov’s perception of cinematic beauty is rooted in truth, depicting the camera as the ultimate weapon of veracity, George Méliès would have argued that the beauty of cinema came in the form of deception. Méliès often emphasised the filmmaker’s ability to fool the audience in order to lure them into a world of pure fiction. His film A Trip to the Moon incorporated a slew of gorgeous painted backdrops, special effects and costumes to create a beautiful lunar landscape, the likes of which had never been seen on film before, in order to transport his audience into worlds they never thought possible.

Suffice to say that the art of cinematography has become more than the placement of a camera. However, despite the development of distinct modern techniques, clear visual communication remains the most important aspect of cinematography. Communication is defined as the ‘exchanging of information by speaking, writing, or using some other medium’. This suggests that cinematographers must consider the suitability of a specific cinematic technique in conveying the information required from the scene to the audience. Indeed, cinematography thrives when the filmmakers are able to prey on tropes that have often guided the instinct of the audience, subverting expectations and crafting a compelling narrative.

Clear visual communication remains the most important aspect of cinematography

The common thread throughout the work of Welles, Vertov, Méliès and all those that have come after, is that film is a vessel for such artists to demonstrate their own visions, delivering a narrative to evoke emotion and highlight subtleties often overlooked. While all filmmakers aim to share their stories with the world, they often utilise their cameras in distinct manners. Diverse stories are able to show us beauty unbeknownst to us, hidden in plain sight but beyond our own collective imagination. Experiencing a film for the first time as a member of an audience, an experience that has been seldom possible throughout the last eighteen months, is a rare opportunity to feel part of a unique community.

Films are the stories that we tell ourselves, but more importantly, films are the stories that we share. So, what makes a film beautiful? The long and the short of it is this: we can all be filmmakers. Anybody who picks up a camera with an undeniable urge to tell a story is a filmmaker. Emotion can be equally evoked through the use of a smartphone camera as it would be through the latest RED digital camera. Your story is equally worth telling as the latest tentpole blockbuster, and there is a certain beauty in that possibility.

Comments