The UK’s proposed drugs policy update: should we be treating addicts as patients instead of criminals?

TW: drug usage, mention of needles

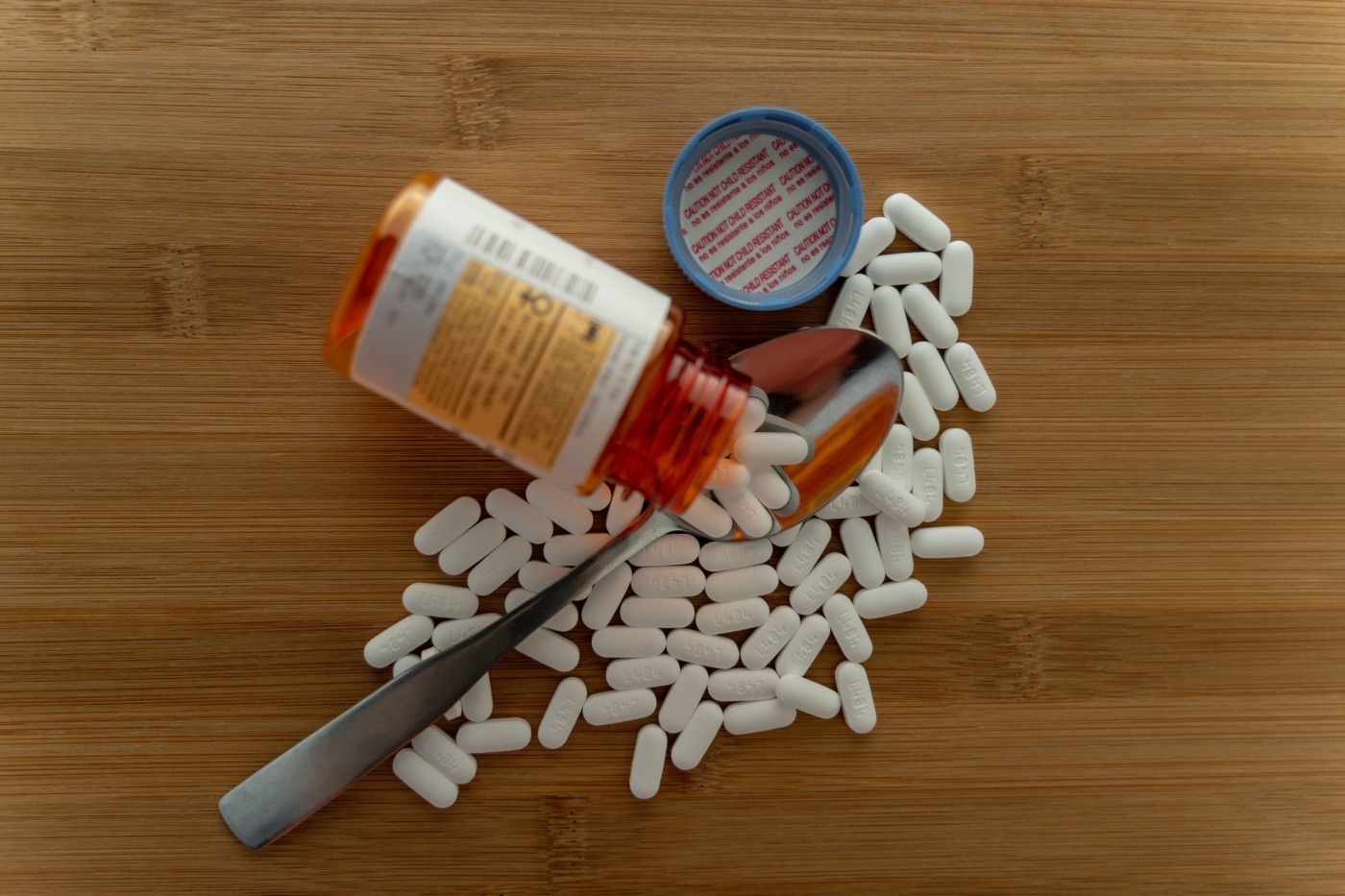

Early this July, the second part of an independent review into the UK’s drug policy was released. This newest document concludes a year-long analysis commissioned by the Home Office and led by former government health advisor Dame Carol Black. Black has previously said that she believes that addicts in this country are treated differently from sufferers of other illnesses and that misusers should be managed as patients, not criminals.

Before the report had even been released, Black’s recommendations had been welcomed by lawmakers. Chair of the Conservative Drug Policy Reform Group, Crispin Blunt MP, stated: “If drug misusers’ issues were dealt with as a health problem, rather than as a criminal justice problem, we’re likelier to have a much healthier and better society as a consequence.”

The Misuse of Drugs Act, which saw its 50th anniversary this year, forms the foundation of the UK’s current drug policy. The law categorises drugs into different classes, each associated with a different criminal sentence. The bill was implemented in 1971 when, at the time, annual deaths attributed to drugs in the UK were under 100. In 2019, England and Wales saw this figure rise to 4,393 – the highest it had reached in 25 years.

At the forefront of Black’s recommendations is getting addicts into treatment rather than through the criminal justice system

However, Blunt – as well as a group of over 50 MPs and peers who have called for the Misuse of Drugs Act to be replaced – do not represent the views of most in Parliament. The Minister for Crime and Policing, Kit Malthouse, has refuted these ideas – saying: “We have no plans to legalise drugs. Legalisation would send the wrong message to the vast majority of people who do not take drugs.”

Black’s report declares that the UK’s treatment of drugs and drug misusers is “not fit for purpose” and that drug use acts as a substantial barrier towards Boris Johnson’s ‘levelling up’ agenda. The review is heavily critical of successive Conservative governments’ budget cuts that have left services inadequately funded. Black’s team also notes that drug-related deaths occur disproportionately in deprived areas of the country, particularly in the North of England.

Overall, the report makes 32 recommendations for the government to better deal with the drug epidemic that the country is facing. At the forefront of Black’s recommendations is getting addicts into treatment rather than through the criminal justice system. Additionally, Black stresses the importance of providing greater support in other areas of addicts’ lives – such as housing, combating unemployment, and improving mental health services.

Public Health England estimates that by implementing Black’s recommendations, the government could save £4 for every £1 spent

In response to Black’s report, the government has announced that they will be creating a multi-departmental unit in order to better tackle drug abuse in the country. “The government faces an unavoidable choice: invest in tackling the problem or keep paying for the consequences,” Black has commented.

The report calculated that dealing with illicit drug use costs over £19 billion or £58,000 per user annually. However, Public Health England estimates that by implementing Black’s recommendations, the government could save £4 for every £1 spent. Black stated, “Failure to invest will inevitably lead to increased future pressures on the criminal justice system, health services, employment services and the welfare system.”

In addition to increased spending, Black urged the government to establish a central Drugs Unit which would be responsible for analysing the actions of various government departments and holding them to account.

The report also criticised the use of one of the most common metrics of success in drug treatment services: the number of people who are discharged without returning within six months. Not only does this ignore the long-term struggles faced by addicts, but is also often tied to local authorities’ funding. Black has recommended the government recognise that “addiction is a chronic health condition, and like diabetes …, it will require long term follow up” to avoid issues of relapse. She warned that the system must not let sufferers “fall between the cracks”.

Labour MP Grahame Morris has suggested that the UK should look to other countries, such as Portugal, for evidence for this approach’s success. Before 2001, Portugal suffered one of the worst rates of overdose deaths and HIV infections (caused by needle sharing among drug users) in Europe. In response to this, the Portuguese government established a committee of doctors, psychiatrists, judges, and other experts to devise a solution.

Portugal changed the classification of personal drug use from a crime to a misdemeanour. According to Dr João Goulão, one of the experts behind the changes, decriminalising drugs “(decreased) stigma and (promoted) the approach of drug users to the health and social responses that they needed.” By 2009, it was evident that both drug-related deaths and HIV infections were decreasing.

If someone dies because we’ve allowed it, who’s responsible?

– Steve Turner, Police and Crime Commissioner for Cleveland

Proponents of repealing the Misuse of Drugs Act point to Portugal as evidence for the success of decriminalisation. Morris said, “It would be wonderful to think we could live in a drug-free Utopia but it isn’t reality.” Advocates of the changes argue that by treating addicts as outpatients instead of criminals – and providing them with the resources and support they need – we can reduce deaths and help sufferers change their lives for the better.

However, critics say that this system will not work in the UK as it did in Portugal. The Police and Crime Commissioner for Cleveland, Steve Turner, has argued, “If we legalise cannabis, then people will try harder drugs, like cocaine. If we legalise cocaine, then people will go on to something else.” He added: “If someone dies because we’ve allowed it, who’s responsible?”

Although, as Crispin Blunt points out, this was the so-called ‘British-system’ before the Misuse of Drugs Act of 1971. Opiate addicts (which represented nearly half of all drug poisonings in 2019) could be prescribed safe quantities of medical-grade heroin or morphine by their doctor, providing them with a safe way of escaping their addiction without the fear of being criminally charged.

Blunt argues that the stigma attached to drugs has made it difficult to develop medicines from cannabis or psychedelics

One campaigner, Pat Hudson, whose son Kevin died of a heroin overdose commented: “The stigma of illegality prevents young people seeking help.” Hudson also noted, “Drug policies are killing young people rather than the drugs themselves.”

Additionally, Blunt argues that the stigma attached to drugs has made it difficult to develop medicines from cannabis or psychedelics to treat other conditions. In the UK there have been several cases of people having to enter into legal fights for cannabis-based medication to minimise symptoms of conditions such as epilepsy.

Despite the recent report, the government shows no indication that it will change tack away from what Blunt calls the “policy of total madness.” While Blunt and Morris represent a small but impassioned faction in the government, they are unlikely to substantially influence UK policy within the Commons in the foreseeable future.

Conservative MP Charles Walker explained: “I’m not sure there’s a huge appetite amongst politicians and I’m not sure there’s a huge appetite amongst the public to do much more on drugs.” At the moment, it seems that the current government’s focus is concentrated on things other than reforming drug policy, and there is little reason to believe that this will change at any time in the near future.

Comments