The killer’s gaze in ‘Manhunter’ and ‘Silence of the Lambs’

Michael Mann’s psychological-thriller Manhunter (1986) and Jonathan Demme’s psychological-horror movie Silence of the Lambs (1991) share a serial killer (Hannibal Lecter), and each has a dogged FBI profiler as a protagonist, but the comparisons stop there. Mann’s film deftly eschews both traditional horror tropes and Hitchockian suspense clichés, instead soaking itself in neon and technology, diving into the disturbed mental state of its lead.

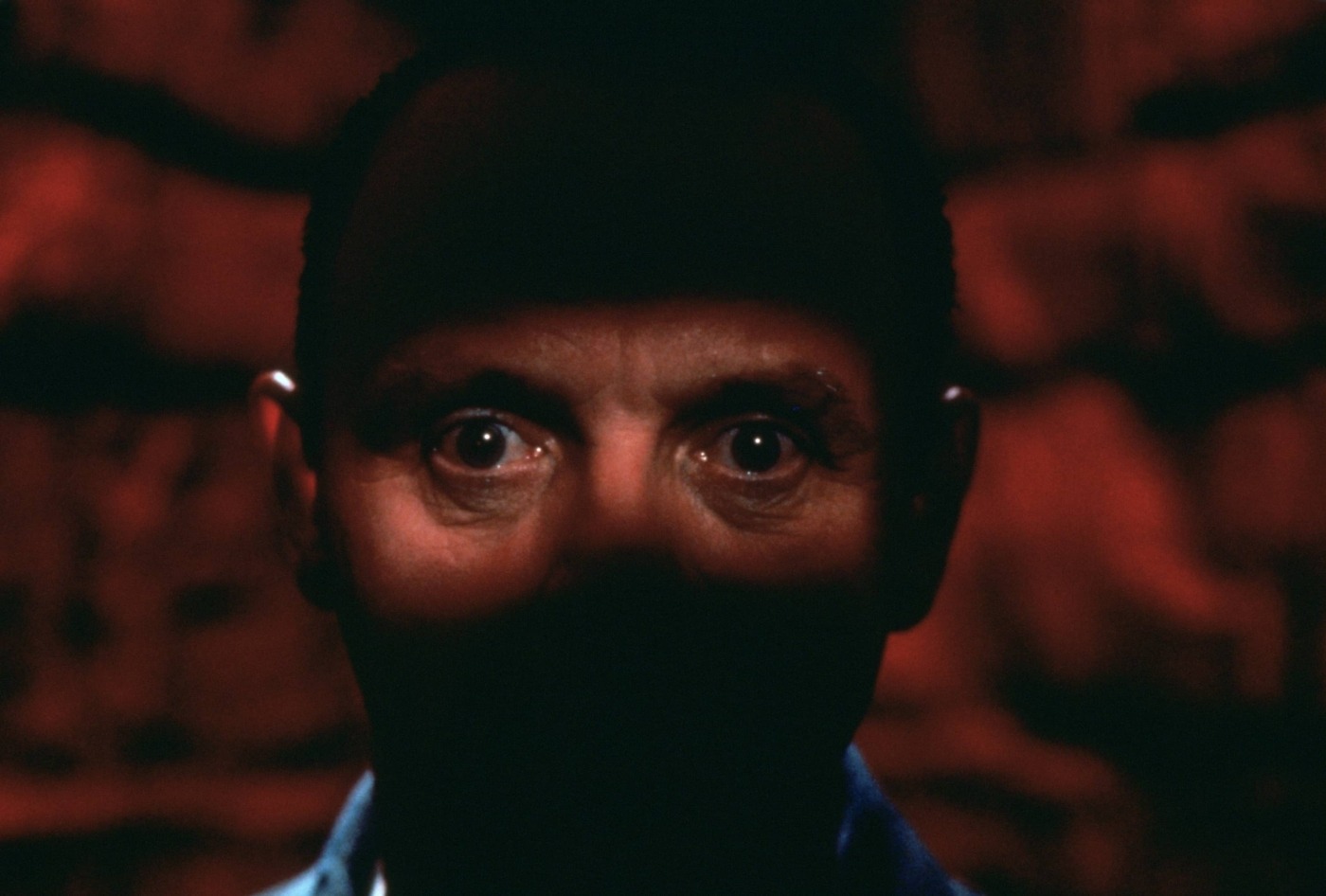

Conversely, Demme’s horror film knowingly indulges in Transylvanian horror tropes. It’s a film of dingy brick-walled basements, howling kidnapped captives and a maniacal lesser antagonist who speaks, breathes and salivates like Count Dracula on steroids. Crucially, a key difference between Mann’s alternative disturbing thriller and Demme’s enjoyably pulpy southern gothic horror classic is in how each uses the camera to conjure up the gaze of their respective killers.

We feel sickened and scared by the killer’s gaze, but in fact we are a privileged audience

Manhunter begins in the POV of Francis Dolarhyde, its serial killer antagonist. We follow all that Dolarhyde sees as he ascends the staircase of a family home, enters the parent’s bedroom and shines a light on the two lives that he will soon claim. Only when the mother wakes and meets his gaze are we given respite from the horror of this introductory vision, as we cut to the film’s titles. Was this opening POV a blessing or a curse? We feel sickened and scared by the killer’s gaze, but in fact we are a privileged audience. For the remainder of the film’s two hours, FBI profiler Will Graham (William Petersen) will do all in his power to achieve the exact viewpoint that the audience has already been granted.

We follow Will as he visits and revisits Dolarhyde’s crime scene. Mann’s placement of the camera in the first visit ensures that we can understand that Will is still separate from Dolarhyde’s vision. With the exception of a few brief moments, Will Graham is always kept in the frame, making him a passive observed figure rather than a controlling observer. Will’s job is to think as the killer thinks, move as the killer moves and crucially, see as the killer sees. When Will is on the scene he arrives at night (just like the killer), shines a torch (just like the killer) and follows the killer’s exact movements, and yet he can’t fully access the killer’s vision. To catch his man, Graham knows that he must see exactly what the killer saw. Mann’s camera understands this fully.

In a later crime scene visit, we get a shot that appears at first to be a POV, before Will is brought into the frame. We then get more and more of Will’s POV; we feel him getting closer and closer to achieving the killer’s vision. He achieves a fleeting glimpse of Dolarhyde’s precise vision later in the story, but Graham achieves complete synchronicity with the killer only when he watches the victim’s home movies. This sequence is filmed by Mann as Graham’s POV of a flickering TV screen.

Mann … implicates the very act of watching movies as a gateway to obsession and violence

The profiler correctly deduces that he is seeing just what the killer has seen, that Dolarhyde has been in possession of these home movies and that he is their developer. The recorded image, poured over and absorbed by the killer, is scrutinised by Graham until he realises that he has finally achieved the killer’s vision, all on video. Here, Mann not only uses camera placement to demonstrate Graham and Dolarhyde’s visual unity but implicates the very act of watching movies as a gateway to obsession and violence. The viewer is therefore led to identify with both the killer and the cop.

In Silence of the Lambs, seeing and being seen is just as crucial. Here, we feel the male gaze on our skin as Agent Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster) is stared at, objectified and penetrated by the eyes of almost every man she encounters, ranging from terrifying killers, to fellow agents to a lecherous psychiatrist. The looks that Clarice endures are varied but always unwelcome: sexual, predatory, sceptical, questioning, dominating.

We see as Clarice sees until the very end of the film when we enter the point of view of the movie’s killer: Buffalo Bill. This famous, harrowing ending sees Clarice trapped in a pitch-black basement. She can’t see the killer, but Buffalo Bill’s night-vision goggles allow him to see her. This is Jonathan Demme’s best directorial flourish in the entire film, a perfect rug-pull moment. After we become accustomed to Clarice’s guarded vision and ability to stare back, we now see a defenceless Clarice being coveted, visually dominated and possessed.

We see Bill’s hands move as if to stroke her face and we follow him as he silently stalks her. By allowing us to rest uncomfortably in the killer’s gaze, Demme ends his film with the logical extension of every little uncomfortable stare that Clarice has had to endure: the gaze of a psychopathic killer in complete control. What destroys Bill is the same action that ends the introductory POV in Manhunter: the prey meets the killer’s gaze. Clarice sees Bill, and in so doing removes his power advantage. What was voyeuristic and one-sided is now a dialogue. The killer dies.

Demme’s film is about conflict and determination, Mann’s is about a disturbing longing for unity with a murderer

The ending to Silence of the Lambs therefore reveals Demme’s more literal approach to the source material. Clarice wins by meeting the killer’s gaze and denying him his power. The camera captures this moment perfectly, breaking away from Bill’s gaze as soon as Clarice meets it. In Manhunter, Dolarhyde’s POV is lost when his prey sees him, but she is still doomed. The killer in Mann’s film is instead defeated when his gaze becomes one with the protagonist’s. Only when the obsessive vision is synchronous can Graham know who Dolarhyde is. Demme’s film is about conflict and determination, Mann’s is about a disturbing longing for unity with a murderer. All of this is conveyed superbly through where the two great directors chose to place their camera.

All cinema is noise and vision. Great directors take advantage of both elements at all times.

Comments