Love, death and duty: why Powell and Pressburger matter

The Red Shoes. Black Narcissus. A Matter of Life and Death. Perhaps you’ve heard of these films before, either through an elderly relative, a charity shop DVD spine or a mid-afternoon screening on ITV4 on some long-forgotten summer weekend. What a cruel fate. These films should never suffer the indignity of being relegated to semi-obscurity. Everyone should know them, and everyone should watch them. The timeless cascades of visual poetry that Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger (known collectively as The Archers) brought to British cinema deserve that much.

Why should you want to watch their films? Why do they matter? The answer is simple. If you’ve ever felt an overwhelming tension between an unquenchable desire and an unavoidable duty, then you cannot truly visualise your feelings until you have seen a Powell-Pressburger production.

Powell and Pressburger’s films are saturated with contradictions and impossible desires

Powell and Pressburger’s films are saturated with contradictions and impossible desires, the push and pull between love, death, friendship and service. The tension and strain between these central components of human existence recurs time and again in their most celebrated stories. For example, Black Narcissus sees Deborah Kerr as Sister Superior Clodagh, tasked with governing an uneasy order of nuns occupying an Indian mountain palace once used by the local royalty to engage in carnal pleasures.

As the high altitude, inherent palatial eroticism and the irresistible charms of David Farrar’s local agent Mr Dean exert their steady influence over the small, fraying group of nuns, the holy order dissolves into sensual chaos. Jack Cardiff’s luscious cinematography heightens the vivid atmosphere of the picture, luring you into an intoxicating world where Sister Clodagh is faced with a truly impossible task. This pristine, pure, virginal order of nuns doesn’t belong here and cannot stand. Their senses cannot resist their environment and their fall from duty into desire is inevitable. It’s not quite Paddington 2.

A Matter of Life and Death is a very different story, a completely tonally distinct film but one that shares the same key themes of love, death and service. David Niven stars as RAF pilot Peter Carter. He’s a doomed man. His Lancaster Bomber has been struck by Nazi artillery and he’s been left without a useable parachute. After one last radio transmission in which Peter finds the time to fall in love with the voice of American radio operator June, he jumps into the unknowable abyss of death.

Here, Powell and Pressburger’s fantastical elements kick in. Peter survives. This is due entirely to an error made by the angel tasked with bringing him to heaven (he couldn’t see Peter’s falling body through the thick English fog). The film then sees Peter’s case picked over by a heavenly jury. His friend and intellectual companion Dr Frank Reeves must make the case that Peter’s love for June is a strong enough reason to let the man live. His inevitable duty to the bureaucracy of angels is defeated by the irrational force of love. Peter’s wartime service makes death almost a guarantee, but love wins.

His inevitable duty to the bureaucracy of angels is defeated by the irrational force of love

War crops up again in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. This Technicolor historical epic follows the life of Clive Wynne-Candy, a British army official who falls passionately in love with Edith Hunter (Deborah Kerr), an Englishwoman who becomes betrothed to a German soldier with the rather wonderful name of Theo Kretschmar-Schuldorff. The tussle between love and service consumes Clive’s life.

Hopelessly in love with Edith but restrained by his close friendship with Theo, Clive keeps his feelings to himself. It’s what an honourable British serviceman should do. Women who resemble Edith appear again and again in Clive’s life. He fights in a war with his best friend serving on the other side. Clive is a garrulous, warm, romantic man, but he chooses to live quietly, pursuing the women that remind him of a love that he has lost forever.

We watch Clive age, see his friendship with Theo tested by the humiliation of military defeat and then rekindled by Theo’s utter rejection of Nazism. In an iconic exchange, Theo challenges Clive’s obsession with honourable service and codes of military conduct, telling his friend that he must change his understanding of war or “there will be no methods but Nazi methods”. Duty, friendship and love (both platonic and romantic) are imbued in the very celluloid of this movie. The central performances by Roger Livesey, Anton Walbrook and Deborah Kerr are three of the best that you’ll see in any film. They form a love triangle without tropes, suffused with genuine warmth and compassion.

Duty, friendship and love (both platonic and romantic) are imbued in the very celluloid of this movie

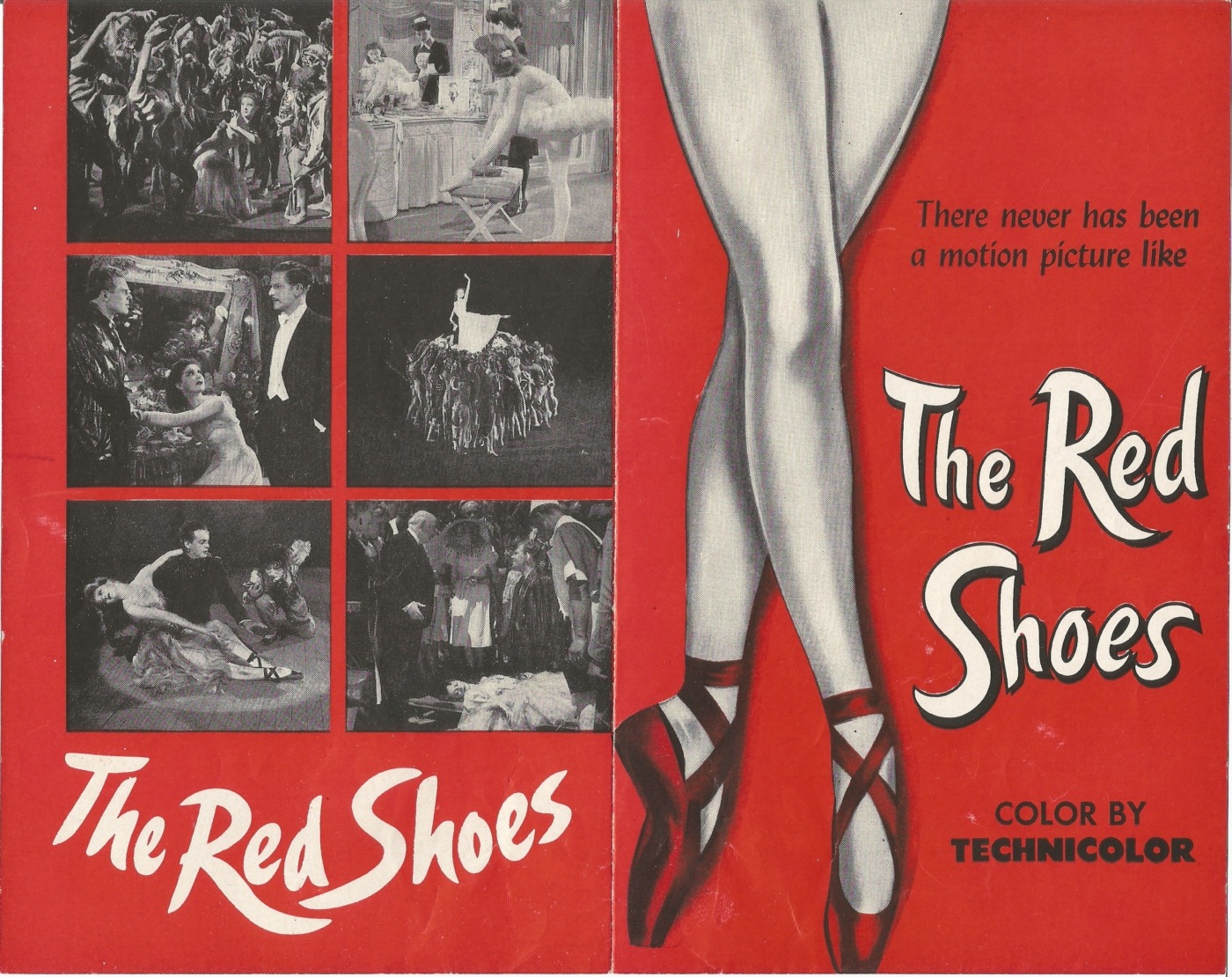

The glorious, mesmerising culmination of these recurring thematic obsessions is the Archers’ ultimate triumph: The Red Shoes. With the duo’s frequent collaborator Jack Cardiff creating images of jaw-dropping pictorial splendour, and a rock-solid cast including ballerina Moira Shearer, domineering impresario Anton Walbrook, amiable conductor Esmond Knight and earnest lovestruck composer Marius Goring, Powell and Pressburger created a ravishing dreamlike cinematic poem of ambition, tension and inevitability that stands as an enduring landmark of British cinema.

An adaptation of the Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale, the film follows the story of Vicky Page, a ballerina who becomes a star thanks to the attention and devotion of Boris Lermontov, a mysterious and obsessive chief of a ballet company. After falling in love with composer Julian Craster, Vicky finds herself torn between her irrepressible urge to dance and the love and affection of her husband. Duty, love and obsession boil over into a spellbinding final act, where the eponymous shoes decide Vicky’s destiny.

There’s far more that warrants mention when discussing Powell and Pressburger, but by focusing on their thematic preoccupations, I hope to demonstrate that great cinema never loses relevancy, no matter its age. Powell and Pressburger’s films aren’t just great. They’re immortal.

Comments