‘The History Makers’: why Random House’s decision to pull Richard Cohen book is historic in itself

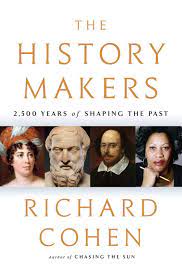

US publisher Random House has reportedly decided not to publish The History Makers by British author Richard Cohen after he failed to include enough Black historians, academics, and writers. While still set to be published in the UK, the current fate of the book abroad is uncertain; Cohen and Kathy Robbins, his wife and top US literary agent, are currently searching for another publisher.

The book is described by publishers Weidenfeld & Nicolson, who have decided to still publish the book in the UK, as “an epic exploration of who writes about the past and how the biases of certain storytellers continue to influence our ideas about history today”. The text explores over 2,500 years of history writing through the works of figures such as Tacitus, Shakespeare, and Voltaire.

It is only in a rewrite of the book that individuals such as the 16th-century Berber Leo Africanus, abolitionist Frederick Douglass, sociologist W.E.B Du Bois, author Toni Morrison, and historian and journalist CLR James were included. Cohen was asked to add in Black historical figures after criticism of the original draft being too white. Cohen has attributed the text needing to be rewritten for American audiences due to “the publisher’s sensitivities.” Yet, the book has still been pulled from publication.

To publish another book that views Black historical figures as an afterthought, and reinforces a white dominance in history, would be tone deaf

I can understand that the rewrite meant extra time and effort spent by Cohen, who spent almost a decade researching and writing the book. But I’m still unsympathetic to the book being pulled. Cohen’s seemingly poor attitude to having to do further work highlights exactly the issue with the book. By attributing the rewrite to his publisher’s wants, he fails to recognise that his research should have been more encompassing in the first place and the importance of documenting Black people and other marginalised groups in history.

Through framing the rewrite as being ‘about another 18,000 words’ Cohen conveys that Black people and their role within history are an afterthought and an additional burden to look into – one he would not have thought about unless prompted by external figures. He would have not included these important historical figures; he also views their inclusion as a ‘sensitivity’ to political correctness and the current contextual climate, rather than a vital part of the history of the world.

Cohen’s seemingly poor attitude to having to do further work highlights exactly the issue with the book

It is perhaps for this reason that Random House pulled the book. It could also be down to the fact the book’s publication has coincided with race being central to conversation in US society right now. To publish another book that views Black historical figures as an afterthought, and reinforces a white dominance in history, would be tone deaf. Either way, neither of these are sensitivities, but acknowledgment of the historical erasure of Black individuals from history.

Furthermore, it is particularly telling that the British publisher decided to continue the book’s publication. The Black British history in The History Makers is supposedly sparse. The text does not even directly deal with the Windrush generation, which is often the starting point for limited teaching about race in the UK. Through still publishing the book, there is a reinforcement of the narrative that racial tensions and racial history are all American things. It continues the British historical cannon as predominantly white.

Black British historians have criticised Cohen’s book. David Olusoga, who wrote Black and British: A Forgotten History and Hakim Adi, a professor at the University of Chichester, have both voiced their concerns. Adi said: “That’s how it’s been – as if Africa and the African American had been forgotten… It’s denigrating to the history of the world, and to black people in particular.”

These two Black historians themselves have arguably been ignored by Cohen in his account of history writing. Cohen concludes the book with TV historians such as Simon Schama and David Starkey, who are both white, but not a contemporary Black British historian.

History doesn’t always have to have black figures at its centre. But in a book that identifies people as “history makers” – the people central to historical narratives in terms of past events and the recording of history – it should be essential that these individuals extend beyond the white and western world.

In a book that is described to be looking at whether history can ever be ‘objective’, the author appears unaware of his own biases in telling the tale of historical writing. However, Random House is less oblivious, and appears to be pulling a book hypocritical in nature to its own investigation and narrative. The publisher has recognised that contemporary history needs to do better than those of the past that omit marginalised voices, and have taken a notable stance in shaping the historiographical world too.

Comments