The brilliance of contemporary Kurosawa

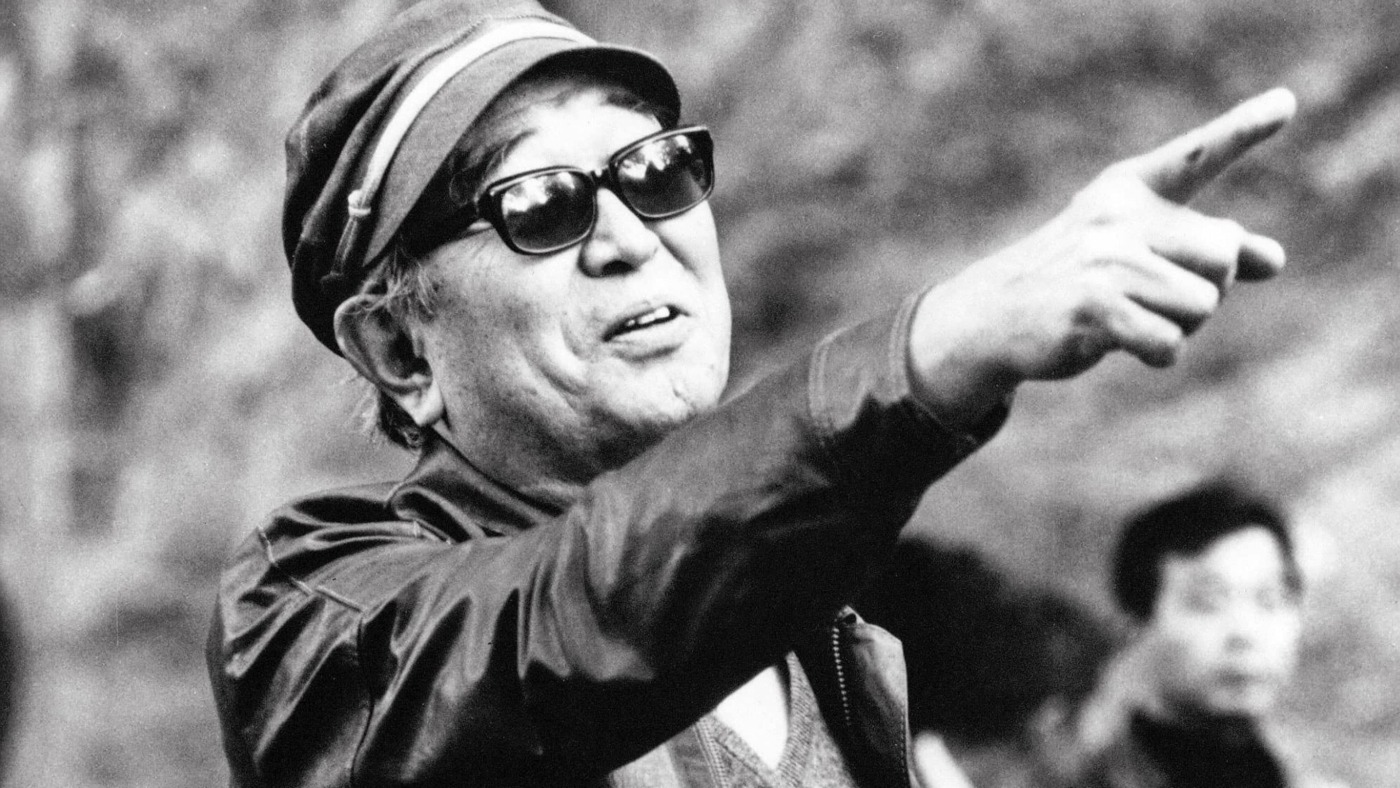

Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai and Rashomon are often considered to be two of the greatest films of all time. I’ve seen both, and appreciate their status in the canon of great films, but have found myself to be an outsider when it comes to the popular adulation that both films continue to receive. This is a feeling not uncommon to any serial viewer of cinematic classics. Appreciation and admiration do not always mean visceral enjoyment, thrills and excitement. In the case of Kurosawa’s two most celebrated films, I find myself to be a respectful non-conformist. In my opinion, Kurosawa’s greatest films are not set in the Japan of centuries past but in the recovering Japan of the post-war years.

Three films in particular showcase Kurosawa’s pessimism for contemporary Japan, his scathing contempt for corruption, his faith in the righteousness of the individual and his masterful skill for composing scenes of extraordinary cold beauty. They are High and Low, The Bad Sleep Well and Ikiru.

High and Low is a crime thriller, following the story of a kidnap. Toshiro Mifune plays Kingo Gondo, a successful businessman who lives in a shining, palatial house on a hill, overseeing the city of Yokohama. Gondo’s elevated social status is literally reflected in his choice of home, clueing us into the class politics that underlie the film’s story. After Gondo’s chauffeur’s son is kidnapped in a case of mistaken identity (the kidnappers intended to snatch Gondo’s son), a hefty ransom is demanded. Paying it would mean that Gondo will lose his position in the company, his wealth, his stability and his home. Gondo’s mansion renders him vulnerable. It can be seen by all in the city, meaning that anyone can look in. Its large glass windows deny Gondo any privacy, turning him from a king in his castle to a helpless creature under a microscope.

Despite its length and status as a 58-year-old foreign language film, High and Low is a punchy, absorbing crime thriller. With its gorgeous TohoScope aspect ratio, intense performances, artistic visual compositions and resonant themes dealing with class, envy and capitalism, High and Low is an accessible, accomplished speeding bullet of a film. It was the first movie to sell me on Kurosawa’s reputation as one of the great directors.

High and Low is an accessible, accomplished speeding bullet of a film

The second film was The Bad Sleep Well. Another riveting crime thriller, this excoriating expression of contempt at post-war corporate and state corruption is a far less conventional film than High and Low. Where the story of Kingo Gondo relies on what may now seem like the commonplace tropes of a kidnapping story, The Bad Sleep Well stands alone as a crime thriller, revenge story, political parable and loose adaptation of Hamlet. The story follows Koichi Nishi (played once again by Kurosawa regular Toshiro Mifune), as a mysterious loner waging a private war against the corrupt Public Development Corporation.

Marrying the daughter of Corporation Vice President Iwabuchi, Nishi patiently orchestrates the demolition of a gang of corrupt corporate crooks, all of whom were linked to the death of a man called Furuya five years ago. Why is Nishi pursuing the destruction of these criminals? Who is taunting Iwabuchi with reminders of Furuya’s death? How can any of this end well? With spectacular locations including a bombed out factory and an active volcano, Kurosawa captures a bleak image of Japan struggling in the aftermath of an apocalyptic war. The film is a personal favourite of director Francis Ford Coppola, a fact that brings the symmetry between the immaculately photographed weddings that open both The Godfather and The Bad Sleep Well into clear focus.

No discussion of The Bad Sleep Well can go without mentioning its startling ending. With a nihilistic pessimism more closely associated with 70s and 80s American thrillers like Chinatown and Cutter’s Way, Kurosawa’s story ends abruptly with a heart-breaking conclusion, suggesting that the corruption goes all the way to the very top. It was a brave film to release in 1960, and it still looks incredible today. Marrying Kurosawa’s expert eye for framing and spectacular visuals with a vitriolic political anger and despair, The Bad Sleep Well is my favourite of his films.

Lastly, in a break from his usual output of crime thrillers and action films, Kurosawa opted for heart-breaking drama with his film Ikiru. Following the last months of a lonely Tokyo bureaucrat dying of stomach cancer, Ikiru could draw tears from a statue. Takashi Shimura’s performance as Kanji Watanabe is unbearably close to the bone, alternating between hope, desperation, love and deep sadness.

Watanabe first reacts to the news of his medical death sentence with a haunting emptiness. He then resolves to live by drinking and spending as much money as he can. After this leaves him even more empty, he begins spending time with a vibrant young colleague. Their conversations and time together make him realise that he has the power to help others before he dies. Using his position as a city bureaucrat, he works tirelessly to clean up a dangerous pool of stagnant water and replace it with a children’s playground.

Ikiru could draw tears from a statue

The intimacy of this film is astounding. Scenes depicting Watanabe curling up in bed and crying, singing a mournful romantic ballad at a noisy bar and gently rocking on a swing in his new playground creation are some of the most truly affecting in all cinema. We identify with Watanabe to the point where he feels like a grandfather. We feel anger at the people around him for not embracing this decent man and realising his loneliness. Most of all, we feel respect and compassion for Watanabe and his valiant struggle to bring some good to the world. This is an incredibly unconventional film for Kurosawa (it feels more like an Ozu film at times) but it could well be his greatest.

Kurosawa’s name is synonymous with the samurai action film, but it needn’t be. For me, his strongest works are set in a time much more recognisable to all of us.

Comments