Nord Stream and Navalny: what you need to know

Nord Stream 2, the Russian project to further its influence in Europe by increasing EU dependence on Russian energy, once again has its future in doubt after the Russian imprisonment of Alexei Navalny. But who is Alexei Navalny, and what does he have to do with a gas pipeline?

The foremost opposition figure in Russia since 2015, Navalny’s anti-corruption investigations and grassroots political activities have been a continuous annoyance to Putin. From coming second in the 2013 Moscow mayoral elections, encouraging protests in 2012, 2018, and 2019 (and 2021), and investigating widespread corruption amongst the Russian elite, his activities have caught the ire of Russia’s powerful oligarchs. These efforts have recently culminated in a 2-hour documentary released on YouTube detailing the extensive corruption and nepotism involved in the construction of a dacha for Putin – dubbed Putin’s Palace – at an estimated cost of ₽100 billion (just under £1 billion).

This ire has not been kept quiet. The numerous attacks and constant harassment – including multiple raids on his offices, assaults of allies and aides, and multiple imprisonments on trumped up charges – eventually came to a head in a poisoning last August, eventually revealed by the investigative journalism site Bellingcat to be a state-sponsored assassination attempt. The same nerve agent used in the Salisbury poisonings, Novichok, was used. Its use, seemingly a modus operandi of the Russian security services, allows Russia legal plausible deniability while also making clear that the attack did indeed come from them – an important aspect in maintaining influence in the post-Soviet sphere.

After five months of treatment in Berlin, Navalny, under threat of arrest, returned to Russia. His flight, scheduled to land at Vnukovo airport, where media and crowds were waiting to greet him, was diverted mid-flight to Sheremetyevo airport – presumably to be able to arrest Navalny without crowds and media watching. As expected, upon landing, Navalny was arrested.

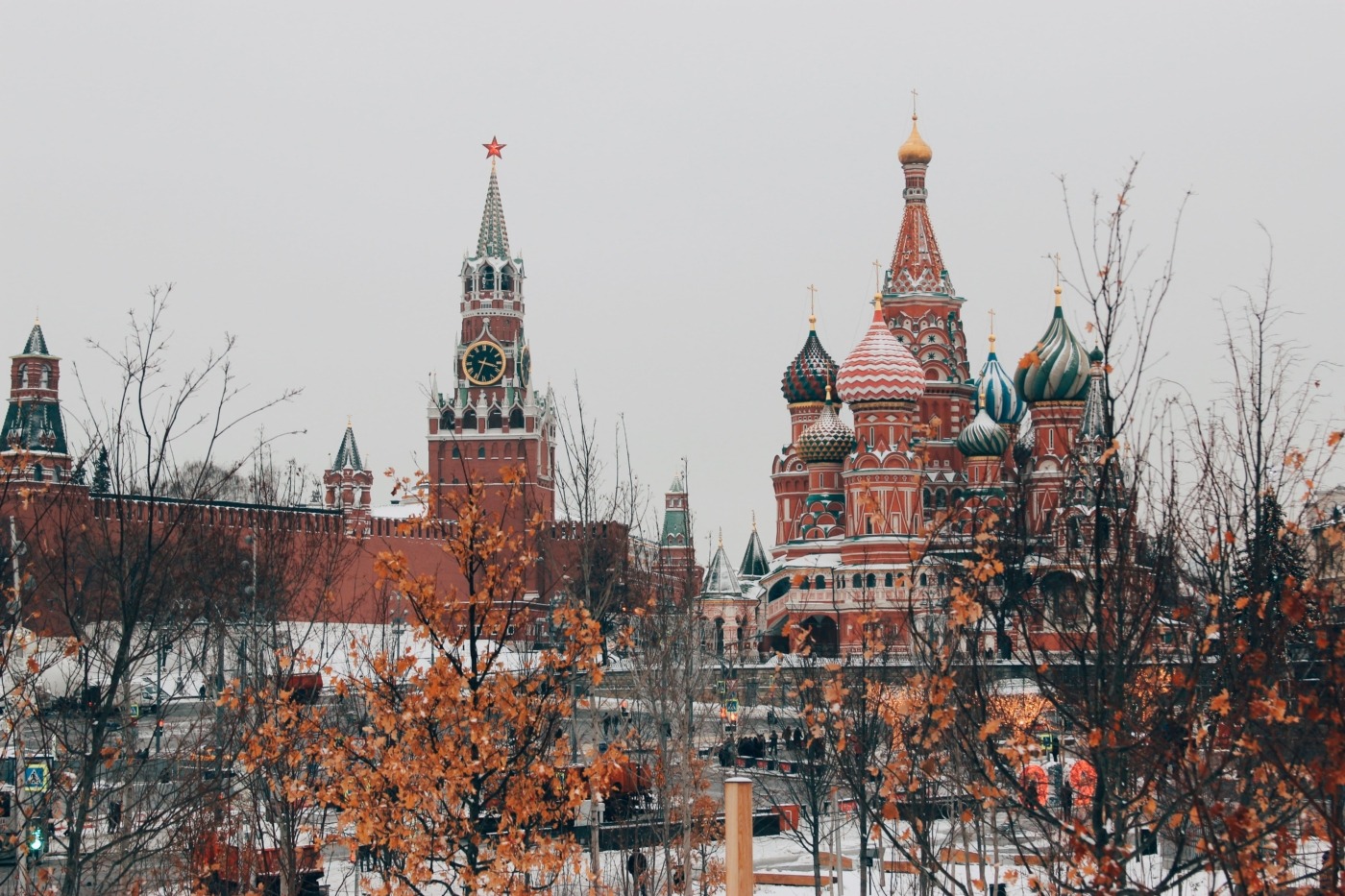

From St Petersburg to Vladivostok, Russians braved the freezing cold and a heavy police presence to express dissatisfaction with the regime

Navalny and his Anti-Corruption Foundation called for protests. Encouraged by Navalny and his team’s wide presence on social media, and high levels of support amongst younger Russians, tens of thousands marched. From St Petersburg to Vladivostok, Russians braved the freezing cold – reaching up to -52C in Yakutsk – and a heavy police presence to express dissatisfaction with the regime. In response, more than 3,000 were detained, with Moscow jail space in such short supply that some of those held were kept on prison buses. The next weekend, the authorities had prepared, shutting off streets and closing metro stations to prevent crowds congregating in one place – more than 5,000 were detained.

Concurrent to these protests, the security services launched a full crackdown on Navalny’s allies and supporters. His brother, spokeswoman, one of his lawyers, and numerous allies and aides have either been detained, placed under house arrest, or subject to questioning and house searches. And on February second, Navalny was finally sentenced to three and a half years in prison.

Unfortunately for the protestors, the Russian Government by now is adept at handling exactly these kinds of demonstrations. Large protests in 2011, 2012, 2013, 2018, and 2019, and the studying of the colour revolutions of Ukraine, Georgia, and Kyrgyzstan, the 2014 Euromaidan Revolution, the 2018 Armenian Revolution, and the 2020 Belarus protests have all led to the Russian state apparatus being skilled in protest management. Indeed, the fact that all but one of those foreign examples is termed ‘revolution’, and not ‘protest’ demonstrates why the Russian Government takes this incredibly seriously – all were similar style protests against similar styles of corrupt, nepotist, patronage-orientated regime. Pressure on social media, targeted internet disruptions, splitting crowds, and – for Eastern Europe – relatively limited police brutality all serve to show that the Russian Government is leaving nothing to chance.

While sanctions are now likely, Russia is used to targeted sanctions against individuals

Higher up on Putin’s list of concerns is the effect that his domestic handling of dissidents has on the world stage. Ever since the death of Stalin, Soviet and Russian governments have tried – often in vain – to keep critics quiet while avoiding condemnation from the West. The latest treatment of Navalny is no different. Even before his sentencing, there were condemnations from the US, the UK, and the EU. Much of Eastern Europe – including Poland, Romania, and the Baltic States – had called for sanctions. The EU Parliament voted overwhelmingly in a non-binding resolution to sanction Russia and stop Nord Stream 2. His sentencing has only intensified such criticism and resolve. While sanctions are now likely, Russia is used to targeted sanctions against individuals. The larger concern for Russia will be the new spotlight on Nord Stream 2, the gas pipeline that aims to pump more Russian natural gas into the EU.

The pipeline would increase EU dependence on Russia for its energy needs

The pipeline, which once complete should take Russian gas exports to Europe from roughly 200 billion cubic meters to 255 billion cubic meters, has long been a geopolitical objective of the Russian Federation. It would increase EU dependence on Russia for its energy needs, which already imports about 45% of its natural gas from Russia – upwards of 75% for many Eastern European countries. This dependence translates into political clout – it can raise prices to pressure the EU (the energy companies are all controlled by associates of Putin), and if needed to, it could turn the taps off to deplete Europe of much of its energy, forcing rationing and potentially sending much of Europe into darkness. This political clout can then be used to deter sanctions, and give Russia more of a free hand in the former Soviet Union. This is why the US, NATO, and most of Europe (with the notable exception of Germany) is opposed to the pipeline. Already under criticism prior to Navalny’s sentencing, France has once again called on Germany to scrap it. However, while international pressure rises, Germany is unlikely to cancel the project. It is more than 90% complete, much of German commerce supports it, and cancelling would likely lead to higher German energy prices and a slew of legal complaints. With regards to Germany, realpolitik will win out.

The future of the pipeline is thus in American hands. The US has come close to killing it before. If the Biden Administration were to impose sanctions such that companies working on the project could no longer do business with the US, most would pull out. There is rare bipartisan support for such a move, and especially now with Navalny’s sentencing, further sanctions are likely. However, the pipeline is, at time of writing, 94% complete. Its future will now be determined by the winners of a race between the slow pipe laying ships, and the potentially slower US bureaucracy to firstly, decide, and secondly, act.

Comments