What life is like as a Paralympian and a Warwick History student

For Kare Adenegan, Paralympian and first-year Warwick History student, one of the challenges she faces in her sporting career, beyond juggling academics and athletic success, is the door she has to get through to get to the Westwood athletics track. We’re the first to pile in, and getting through a set of non-automatic doors in a wheelchair is difficult enough, but requires expert manoeuvring when toting a two-metre-long racing chair. The foyer fills up with her teammates as we talk, slowly evolving into a comical game of Tetris as everyone squeezes in so as not to venture out any sooner than absolutely necessary into the bitter cold. It’s a tight fit, and Adenegan tells me that “December training tends to be quieter” because nobody really wants to train in the cold and the rain.

Having dabbled in other parasports, Adenegan was inspired to take up wheelchair racing after the London Paralympics. Within four years she would be representing GB at Rio. At just 15, she earned her first Paralympic silver medal in the T34 100m, coming second to her teammate and wheelchair racing legend Hannah Cockcroft MBE. Though considerably younger and less experienced, it was not the first time they had raced against one another – Adenegan beat her for the first time in 2015 at a small domestic meet, and would go on to win twice against her in 2018, first at the London Anniversary Games and then at the European Championships. At the latter, she broke Cockroft’s seven-year gold streak. It was at the former that she set a new world record for the 100m, being the first athlete to achieve a sub-17 second finish.

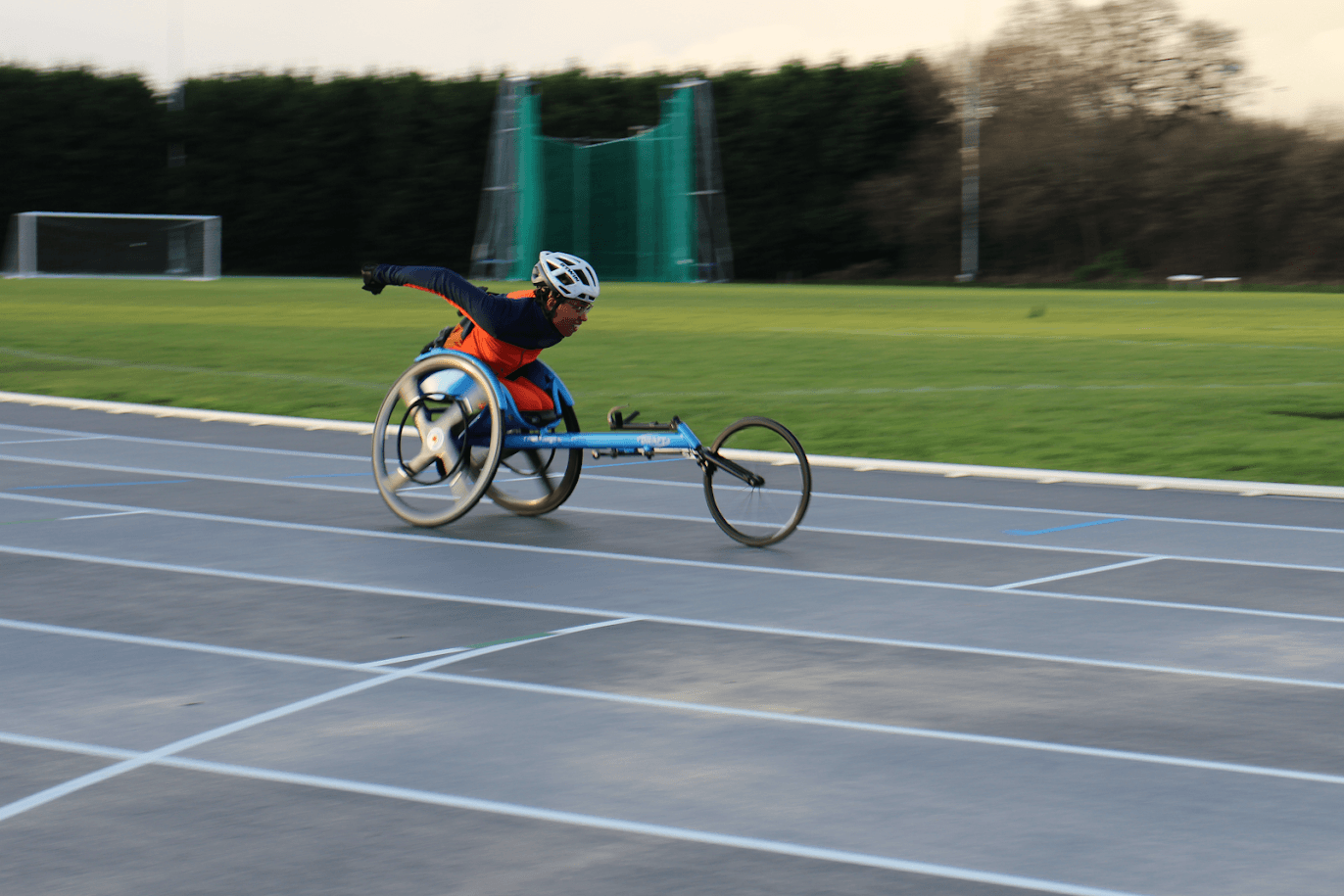

It wasn’t hard to appreciate Adenegan’s skill

With another set of double doors tackled, I found myself on the side of the track, sat amongst a collection of empty wheelchairs, watching the training session. It wasn’t hard to appreciate Adenegan’s skill. Simply getting into the chair looked difficult enough – though hard to tell from afar, a racing wheelchair consists of what essentially is a platform on which to rest your knees with a seat above it. “It’s a bit of a tight fit,” she laughs as she concertinas herself into the chair, essentially sitting on her feet. One of her teammates, Sophie, explains to me the growing number of discarded trainers on the side of the track – eventually, and especially in the bitter cold of this particular training session, you stop being able to feel your feet. Shoes just become an aerodynamic hindrance.

For something that looks so uncomfortable, Adenegan manages to make going around the track look effortless. She tells me Sunday sessions is endurance training, and that’s not an understatement by any means. Even with the third or fourth lap, there’s no let-up in the pace. I’m exhausted just watching. It’s truly amazing that there’s such little recognition of the talent these athletes have. “It always seems to take a Paralympic year for people to be like, ‘oh, wow, we’ve got a Paralympian!’ and even though we’re competing throughout the years it’s only really at the Paralympics that we get that coverage and that people are actually interested.”

While most Freshers spend first term adjusting to the barrage of lectures, seminars, and essay deadlines, Adenegan spent it gearing up for the World Athletics Championships in Dubai. “It was quite strange – it was my first term but I was also getting ready for the World Championships. (Tutors) have been really good; thankfully one of the weeks I missed was reading week, but I came back and I was quite stressed because I was a bit behind with things.” She’s a Warwick Sports Scholar, a scheme run by the University to support sporting talent. It supplements three track sessions a week with gym and physio. “It did feel a lot like it was literally uni, lectures, train, do a bit of reading, train, then do more reading. It’s been a bit intense, but it’s been something I’ve had to do throughout my whole career. I’ve always had school or A Levels or GCSEs.” Competing against athletes who can dedicate themselves solely to training puts her at a slight disadvantage, she admits, but “having the academic side is quite good because it gives me something else to focus on. I don’t think I could just sit at home and train. And, to be honest, I think pushing around campus is like another workout!”

When I enquire about the price of a chair – let alone a sole pair of wheels – James and Sophie reply with ballpark figures that make me wince

Wheelchair racing clubs are few and far between; Coventry Godiva Harriers serve athletes, amateur to professional, from across the Midlands and from as far afield as Lincoln. Though in theory, most tracks are suitable for training wheelchair athletes, it’s a lack of coaches that proves the real problem. Adenegan’s coach, Job King, has been training wheelchair athletes at the track since 2011. Also in attendance is James, who tells me he became involved with the club after meeting Adenegan in a bike shop a year or so before – he jokes that he has become the club’s honorary mechanic, adjusting Sophie’s wonky wheel as Adenegan warms up. “I bought my spare wheels,” she tells him, “Just in case.” When I enquire about the price of a chair – let alone a sole pair of wheels – James and Sophie reply with ballpark figures that make me wince. They have spare chairs for those starting out, but those who are looking to get stuck in are looking at thousands of pounds for the essential equipment. It’s a huge initial outlay when the able-bodied equivalent really requires nothing more than a pair of shoes. And as Adenegan points out, it’s not just a matter of the athlete’s performance in competitions – the texture of the track, a slightly loose wheel, or weather conditions can all make or break a race. “If there’s a headwind, you haven’t got a chance. A tailwind’s great though.”

She tells me that visibility is key in parasports – not only sponsorships for funding equipment, but also to inspire others to take up the sport. But what’s crucial is the attitude people take towards para-athletes, and that they are treated with the same regard and respect. “We need the support, but we don’t need patronising. They’re almost like ‘oh well done, you’re doing sport!’ They’re not respecting the fact we’re training really, really hard. There’s still work that needs to be done – I don’t mind people calling me inspirational, but we need people to recognise that we’re doing sport. Not everyone can just be a Paralympian, the same as not everyone can be an Olympian.” Her talents were recognised with the BBC Young Sports Personality of the Year in 2018, the first wheelchair racer to hold the title. “It was really big for me. It’s a good way of showcasing parasport. There have been a few, but we need more Paralympians getting the main award, or at least being up for it so there’s a greater audience.”

While most students are thinking about exams, she’ll be focusing on the upcoming Tokyo games

The next few years look incredibly bright for Adenegan – even before she graduates, she faces both the Paralympics and the Commonwealth Games. While most students are thinking about exams, she’ll be focusing on the upcoming Tokyo games. “I’m just keeping focused on medalling and Paralympic medals are just massive. I want to get on the podium and that keeps me motivated.”

With all this lined up over the next two years, graduation seems a long way off. Her plans? “I think after my degree, I’ll take some time out just to focus on sport. At least I know I’ll have that security of the degree. I’ll focus on sport and just see what happens after that.”

Comments