After the Fall: 30 years since the end of the Berlin Wall

“In Berlin, the prevailing winds are from the west. Consequently a traveller coming in by plane has plenty of time to observe the city from above,” writes Peter Schneider in the first lines of The Wall Jumper.

“Seen from the air, the city seems perfectly homogeneous. Nothing suggests to the stranger that he is nearing a region where two political continents collide.” The overture to Schneider’s celebrated 1982 novella neatly captures the singular conflict that divided Berlin, Germany and indeed all of Europe for much of the twentieth century: between West and East, Communism and capitalism, American and Soviet spheres of influence.

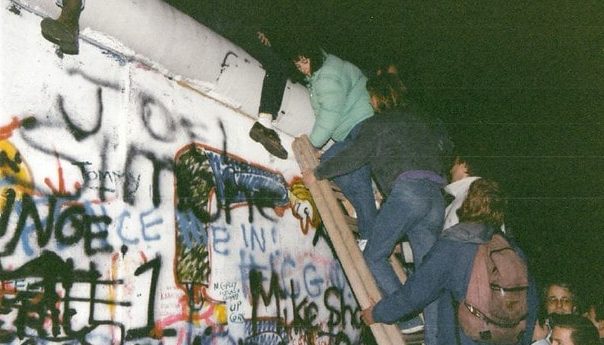

Europe was simultaneously one great continent stretching from Porto to Prague and yet interminably divided down the middle, at the juncture between East Germany (the GDR) and West Germany (the FRG). The Berlin Wall was the most visible symbol of the boundary between the two, but of course the border sliced all the way through Germany, like a scar on the body of a wounded nation. Many lives were lost in attempts to escape the GDR by crossing the Wall; others were killed in failed uprisings against the Soviet government.

The Berlin Wall was the most visible symbol of the boundary between East and West but of course the border sliced all the way through Germany, like a scar on the body of a wounded nation

Still others dared not even express their sympathy, for fear of reprisals from the Stasi, the secret police, or the Volksarmee, the East German military. When the Wall finally ceased to exist on 9 November 1989, in the event that Germans know as the Mauerfall, the destiny of Europe was altered forever practically overnight. Indeed, in the early 1990s the historian Francis Fukuyama went so far as to declare “the end of history” with the demise of the Communist system. Thirty years later after the fall of the Wall, however, it has become increasingly clear that the optimism that sprang from the ruins may turn out to be in vain. Europe is again bitterly divided, but by the anxieties of the twenty-first century, not those of the twentieth. History has not yet ended.

Though the Mauerfall today seems an inevitable product of circumstance, in the 1980s few Germans dared to dream that it could even be a political possibility. “Nobody in my family, or amongst my friends, teachers and peers, ever imagined that Germany would be reunified in the ‘80s. We were sure that it would never happen,” says Elisabeth Herrmann, head of German Studies at Warwick, who was 22 when the Wall came down. Jan Palmowski, also in the German department, agrees: “What also struck me, in hindsight, was that we simply did not see the collapse of the Wall coming.”

“Nobody in my family, or amongst my friends, teachers and peers, ever imagined that Germany would be reunified in the ‘80s. We were sure that it would never happen,” says Elisabeth Herrmann

Now a professor of modern history, Jan remembers entering the GDR with an American friend when he was a first-year university student in April 1989. “It was just inconceivable that things would change, even though we knew of course they were changing in other socialist countries,” he recollects. Seven months later, the Iron Curtain was gone forever. But for those born and raised in West Germany like Elisabeth and Jan, the stark contrast between the two sides of the border still linger in the memory. “We spoke the same language and shared the same culture, but there was so much we did not understand,” says Jan, who would travel to East Berlin every year as a teenager.

Jan and his friends had to exchange their West German marks for the East German equivalent, but any leftover money from the GDR would be useless back home. So they were forced to spend all of it: at the theatre, in the bookstores or at the finest restaurants. “We lived like kings by East German standards, and that did not exactly endear us to the East Germans looking at our expensive clothes, observing the waste we produced,” recalls Jan.

For Elisabeth, the barrier between East and West was as much a mental as a physical one. “It was a wall within our heads. We had no idea what was going on in the GDR: it was a world on another planet,” she says. “It was really strange, and it’s hard to convey to younger generations just how strict that border was.” Authentic information from the East was difficult to come by and was often filtered through the lens of the West’s propaganda machine, which made a concerted effort to discredit the GDR. She adds: “At the time, I was not aware of how much propaganda there was on the FRG side. Communism was a dirty word. What is very important in that context was the Cold War. Germany was where the two superpowers met and there was a lot of fear about a Third World War, especially as American nuclear weapons were stationed in the country.”

For those born and raised in West Germany like Elisabeth and Jan, the stark contrast between the two sides of the border still linger in the memory

When the Mauerfall occurred, most West Germans looked forward to a new beginning, but some feared a repeat of the uprising of 17 June 1953. (That revolt was infamously crushed by the Soviet authorities; indeed the Berlin Wall was constructed in 1961 as a response to this and other sporadic rebellions.) “There was a lot of fear in the air at the possibility of Soviet intervention. For the people in Berlin, yes of course, there was a lot of hope. When the gates opened, then there was hope,” says Elisabeth. “I thought, ‘OK, that’s the end of the Cold War. Wow! That’s the most exciting moment in my life.’ For me, the Cold War was not something very pleasant to live with.”

By contrast, for East Germans, the Mauerfall became an aching source of regret. The country they cherished was no longer recognisable after it was effectively taken over by the West. Nora Michaelis, a German tutor at Warwick, explains: “For the Western people, nothing really changed; but for the Eastern people, everything changed. Many Eastern people were very quickly disillusioned because they lost their home country, their jobs, their factories, their childcare, their institutions, everything they had grown up with.” According to Nora, the gulf between the Western and Eastern experiences of German reunification is only now being fully acknowledged in the public conversation about the Mauerfall. “Only in the last 5-10 years we’ve started talking about this difference in perception and what this has meant in terms of the evolution of Germany,” she adds. “They didn’t even think it was arrogant in the West to take control of the GDR and nowadays people are starting to reflect that maybe it was arrogant.”

Some East Germans have responded by wishing to return to the old Communist ways of life, a notion known as Ostalgie, which was popularised by the film Goodbye Lenin!. “Ostalgie is something that could only come about because East Germans felt their home country was taken away from them,” says Nora. “What Ostalgie is, and what it is often criticised for, is that it only emphasises the positive aspects of the GDR, and it perhaps also romanticises it. People feel better about the past now than they did when they were actually in the past.”

Elisabeth, for her part, is sceptical about such rose-tinted views of East Germany. She explains: “The risk with Ostalgia is that people forget that the GDR was a totalitarian state. Of course, you tend to forget how totalitarian it was when it’s over.”

The social, cultural and economic divides between East and West Germany have continued to persist long after the fall of the Wall. Wenzel Lorenz considers his hometown of Dresden an archetypal East German city and has seen the disparities between East and West first-hand. He explains: “Doctors in the East for example earn about 25% less than the equivalent salary in the West. There’s basically no reason for that.” The East/West divide is an even bigger issue now than in the early ‘90s, because at that time there were low expectations for the East’s ability to catch up economically with the West. “People said: ‘You can’t expect everything to be good right away,’ but now 30 years later there is still a pay gap, there are still inequalities in everyday life,” says Wenzel, 22, who is studying for a Warwick master’s in continental philosophy. Most of the infrastructure had been state-owned in the GDR days, but after reunification the West German government were eager to privatise as much as they could. “They completely ruined what was left of the East German economy,” he adds.

The social, cultural and economic divides between East and West Germany have continued to persist long after the fall of the Wall

Wenzel points out the cultural conflict between East and West Germans, which may not necessarily be a figment of the imagination. He recalls: “When I was young, I always thought it was just something grown-ups talked about, but now I have friends who are from East Germany and have gone to study in West Germany, and they complain all the time about how arrogant West Germans are. It’s not everyone though.”

The date of the Mauerfall, 9 November, carries a significance in German history that stretches far beyond the legacies of the Berlin Wall. The first German democracy, the Weimar Republic, was founded on this day in 1918 in the wake of the First World War. But the prosperity that came with it was brought to an end exactly two decades later when Nazi troops unleashed the first in a series of anti-Semitic pogroms. Jews today still carry with them the trauma of 9 November 1938, which is better known to them as Kristallnacht or the Night of Broken Glass. For Wenzel, this fateful date is imbued with so much political and historical meaning that it is never only about the Berlin Wall. “You can tell someone the story of twentieth-century Germany just by looking at 9 November,” he says. “I think it should be a national holiday, if it makes people more sensitive to the complexity of our past, because what I like about that date is that it shows you both the good and bad sides of German history.”

The fall of the Iron Curtain had implications for the long-term trajectory of Europe, as the reunified Germany came to dominate the EU agenda. Not only did Germany have the willingness and capacity to force Southern European countries to pass austerity measures, but it could also unilaterally allow large numbers of refugees to enter the EU, according to political commentator Benjamin Studebaker. “Austerity and the refugee crisis precipitated widespread radicalisation of the politics of many European states, the effects of which are still unfolding – and include Brexit,” says Benjamin, a PhD student at the University of Cambridge. At the same time, German politics is being changed by the right-wing populist group Alternative für Deutschland (AfD). Originally an anti-Euro movement, the party has developed into a robust far-right force in German politics and has especially sought to capitalise on Eastern areas’ continued economic impoverishment.

The fall of the Iron Curtain had implications for the long-term trajectory of Europe, as the reunified Germany came to dominate the EU agenda

“In the years after the fall of the Wall, many opportunities that we would have had to communicate more with people in the East about what they wanted were not taken,” says Nora. “Now they are getting their revenge by voting for the AfD, because we gave them the feeling of perhaps not caring about what they felt.” Although most AfD voters do hail from the East, there are pockets of support in the West, which suggests that class differences may be more important than regional inequalities in explaining the party’s success. “So this is why people say it’s not just an Eastern problem, it’s about people across the country feeling left behind,”she adds. Complicating matters is the fact that the German left has traditionally been associated with the former GDR government, crippling the chance of a major leftist realignment. “This has ensured that German politics would stay well to the right of many other European states,” says Benjamin.

Some remain optimistic that Europe can draw the right lessons from Germany’s decades of division, at a time of unprecedented anxiety for the EU. For younger German-speaking generations in particular, the fall of the Wall is a symbol of how old wounds can be healed if there is the political will to do so. “The fall of the Wall was a European moment as well as a German moment, and this connection brings out a feeling of responsibility among Germans to be Europeans,” says Wenzel. “There are strong personal and historical reasons for Germany to want to continue the European project.”

Eric Decker, a second-year economics student from Austria, is adamant that the unity engendered by the collapse of the Wall should serve as a model for peaceful coexistence among all Europeans. He believes the reunification process is just another stage in the journey towards a united Europe, which began with the Treaty of Versailles that ended the First World War. “This feeling of togetherness should also be the yardstick for navigating the choppy waters in the present, in order to put the goals we have in common before the conflicts that threaten to tear us apart,” Eric concludes.

“That is what we can learn from the past to progress towards a prosperous and harmonious future.”

Comments