Why we lie about reading the greats

If you’ve ever pretended to recognise the opening line of “Well, Prince, Genoa and Lucca are now no more than private estates of the Bonaparte family…” then congratulations – you’re officially part of the 31% of Brits who, according to a Sky Arts survey, have recently admitted to lying about reading such classic literature from cover to cover. Whether you’ve managed to make it through all 1225 pages of War and Peace or not, it is undeniable that there is a strongly-held attitude in society that reading the ‘greats’ makes you cultured. But why exactly do we feel the need to lie about this?

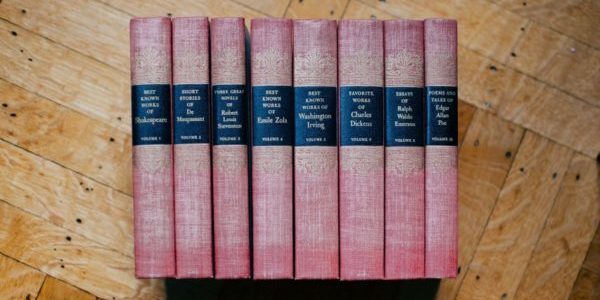

Society teaches that to be cultured, you must be well-read. Not just in the literal term of having read many books, but rather well-read by being well-versed in titles from a list of fiction that feels as if it could have been pulled from the 19th century Oxford English Literature course. Titles such as Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island and Homer’s Odyssey make up the list of books that Brits most often lie about reading, seemingly as if under pressure from their GCSE English teacher.

The real question is, who are we lying to? Perhaps the lies we tell about having dissected the symbolism behind Orwell’s ‘BIG BROTHER’ statements are not really there to impress other people, but rather exist to hide any embarrassment that we might feel at admitting that we are not as cultured as we would like to seem.

In not wanting to appear unintelligent, lying about literature perhaps allows them to disguise any inadequacy they might feel

From a young age, it is enforced on us that the more challenging the novels we read are, the more intelligent we must be. Growing up on the whimsical Harry Potter novels and the neon covers of Jacqueline Wilson, we always understood that there was a next level of literature beyond these – one that would be potentially less enjoyable but certainly more impressive. Internalising such a belief is one that appears to last until adulthood for many, with us preferring to lie rather than admit that we never got around to ploughing through the entirety of Ulysses.

Our need to appear cultured is something that is pressing for many, but by stark contrast seems to be non-existent for some. When asking my flatmates, most said that they would admit to never having even touched anything on the list of greats. However, when asking the older generations of my family the idea of lying in order to ‘disguise their ignorance’ surfaced. For those growing up in an age when leaving school at 14 was an option, appearing well-educated seems to be more of a priority. In not wanting to appear unintelligent, lying about literature perhaps allows them to disguise any inadequacy they might feel compared to those who opted for further education beyond the minimum.

Society might remain ingrained with this idea of being ‘cultured’ and your image as an educated member of society may be, albeit falsely, upheld when you pretend you’ve read all of Anna Karenina

This generational divide is interesting when questioning why some people lie out of a need to appear refined and well-educated. For people my own age, who had no say in staying within the education system until we were at least 18, it is perhaps far easier to laugh off the way that we never even managed to finish Of Mice and Men in Year 10 – without feeling embarrassed about any social stigma that might come with that.

However, for those who do choose to lie, regardless of age, there is always the fear that we will be caught out in an incredibly humiliating way. The horrifying idea of a Tinder date with a self-described ‘Literature enthusiast’ springs to mind, frantically trying to Sparknotes the plot of Great Expectations in a bathroom cubicle with only one bar of service.

Outside of far-fetched online-dating scenarios, however, it seems unlikely this habit of lying about reading the greats will have real consequences. Society might remain ingrained with this idea of being ‘cultured’ and your image as an educated member of society may be, albeit falsely, upheld when you pretend you’ve read all of Anna Karenina. However, in day to day life, the chances of being questioned on our opinions of the greats are practically non-existent, and so it’s safe to say that there’s no real harm in pretending that we have any.

Comments