“Extremely thought-provoking”: a review of ‘Kunene and the King’

The prospect of reviewing Kunene and the King at the RSC made me slightly nervous for two reasons. Firstly, I couldn’t simply google the plot in preparation, because this is an entirely new play, written for the RSC, so I had no idea of what to expect. All I knew was that the play was written to reflect on 25 years of change following the first post-apartheid democratic elections (to paraphrase the RSC’s marketing material for the production). This leads me to the second reason, which is that I didn’t feel that I knew enough about the apartheid to write on the issue with any degree of certainty. Nonetheless I wanted to find out what the play was about, and, having seen it, I’m very glad that I did.

While Kunene and the King has the wider aim of questioning whether racism has really ended simply because the apartheid has, on a surface level it explores wider themes of terminal illness and alcoholism. The plot follows Jack Morris, a famous actor intending to play King Lear in an upcoming production in Cape Town, who is brought together with nurse Lunga Kunene by his struggle with Stage four liver cancer.

The play was written to reflect on 25 years of change following the first post-apartheid democratic elections

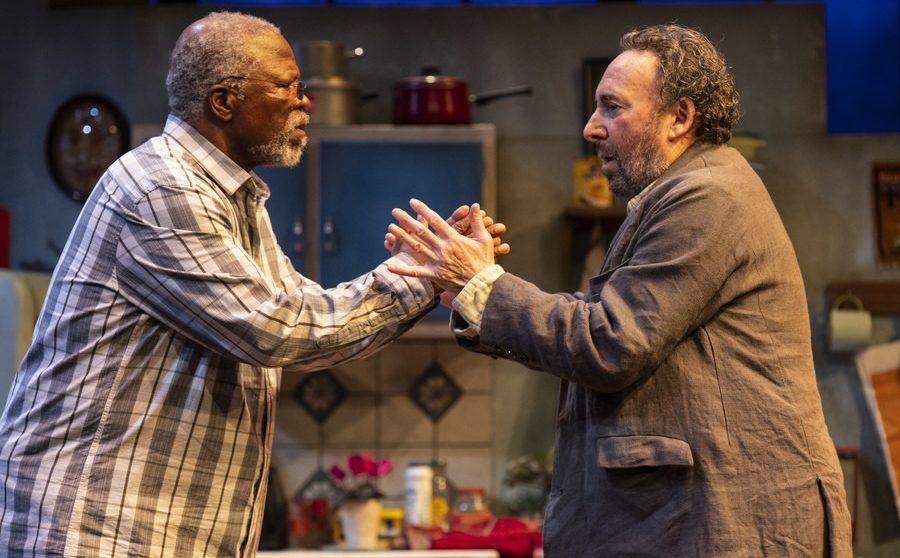

The play was superbly acted – there can be no doubt about that. Staging a two-man play can be difficult as it means that those few actors must carry the whole production; made even more challenging by the difficult themes that this play deals with. However, Antony Sher gives an empathetic performance as a cancer-ridden patient in chronic pain, and the emotion John Kani evokes through his enraged speeches about racism and discrimination can only be described as heart wrenching.

Unfortunately, I was not wholly convinced by certain aspects of the plot. For example, while Morris’ battle with cancer is no doubt emotional, I think that terminal illness was not particularly explored as a theme, and it felt like it was being used more as a plot device. Equally, the play made many references to Shakespeare (through Morris’s preparation for King Lear) which were comedic in the metatheatrical context of seeing the play at the RSC, but which I do feel inherently limits the production from being shown elsewhere – a shame for a play which discusses such widespread and important issues.

The emotion John Kani evokes through his enraged speeches about racism and discrimination can only be described as heart wrenching

It seemed as though the specific choice of Lear was supposed to be a metaphor for some aspect of Morris’ character, but it was not made clear what this was. I do also feel that the play misses a trick in using Shakespeare as a symbol for colonisation. He was, of course, an iconic figure of English culture at the exact time when colonisation was first beginning, and Kunene makes an interesting remark that “Julius Caesar in isiXhosa was the only one of all Shakespeare’s plays allowed to be studied in black schools in those days. Because our teacher told us that the conspirators were like terrorists who tried to overthrow the state and they got their just desserts.” I feel that this would have been an interesting idea to explore, and would have been relatively easy given how much the play discusses Shakespeare.

Despite my reservations about some aspects of the plot, the play overall handled the delicate discussion of racism very well. I particularly appreciated that nothing was 2D – there is no stock villain or hero, and both of the characters are flawed. Kunene at one point asks the very perceptive question: “Why is it that when you talk to me or ask me a question, suddenly I become the spokesperson for all black people. You are you and I am ‘you people, your people’.” Yet only a few lines later asserts: “They should be burnt alive on stakes like you people used to burn witches in the olden days.” It is clear that Kunene still feels incredibly bitter, as he has every right to, but he spends much time solely blaming Morris personally for the apartheid and racism in South-Africa. While he exhibits the racist attitudes that allowed the apartheid to occur, Morris himself was not part of the government that enacted it. Ultimately the play shows the complexity of such issues. Racism is not eradicated just because the apartheid has ended, and we must come together and mutually forgive, just as Kunene and Morris do, in order to move forward.

All-in-all I found the play to be extremely thought-provoking, and it has some very perceptive commentary on issues of institutionalised racism. Yet the play doesn’t feel too heavy, and maintains a comedic air. You won’t walk away completely depressed, but you will be left seriously pondering some of the questions it poses.

Comments