There are no wrong impressions of a book

Is it possible to have a ‘wrong’ impression of a book? Does it matter if my interpretation is different to that which the author intended? What happens if I don’t like a book universally hailed as a ‘classic’? These are the sorts of unhelpful questions readers tend to ask themselves. The answers, for those who are wondering, are as follows: no, no and nothing.

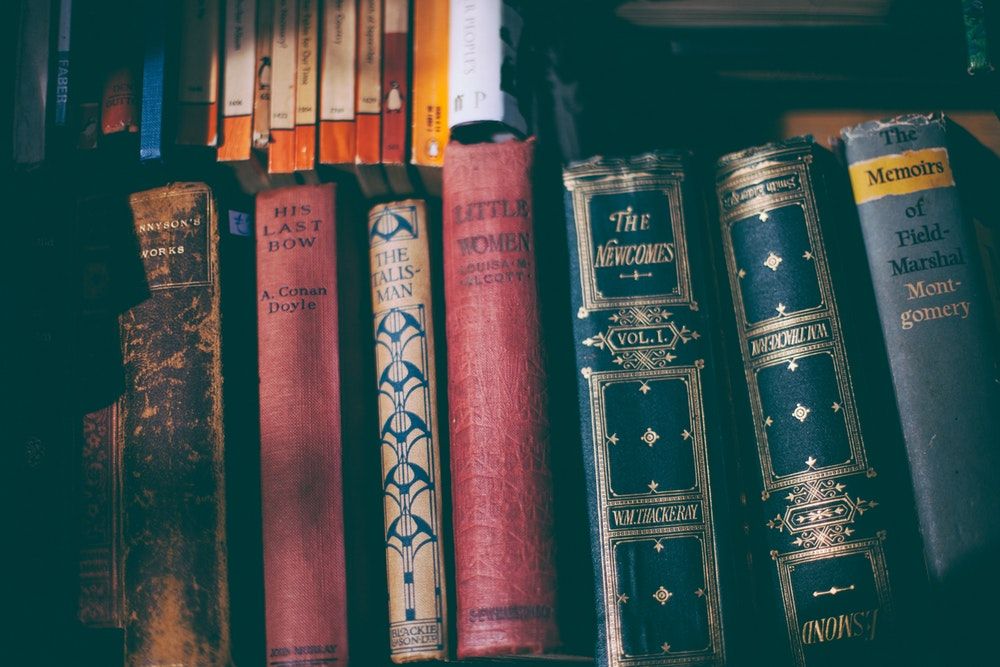

As 21st-century readers, we exist in a literary chain: Margaret Atwood read Virginia Woolf, who read Eliot, who read Milton, who read Shakespeare, who read Chaucer, who read Virgil, and now any English Literature undergraduate gets to read all of them. It’s impossible to replicate the conditions in which any of these literary greats read one another so our understanding of them will inevitably be different. We can’t read Shakespeare in the same way Milton did because we’re not 17th-century anti-monarchists living through the Restoration.

Trying to guess any author’s intentions for their work is almost impossible. Regardless of how many qualifying letters you have after your name, unless Woolf wrote a neat little appendix to Mrs Dalloway declaring “I wrote this book because…”, you’ll never know for certain why she wrote it nor what any of it really meant to her. At any rate, you can’t very well ask her, she died 78 years ago.

We have a shared humanity with every author who’s ever existed, enabling us to look at texts centuries old and claim relatability

So, what do we have left? If we can’t replicate the original conditions of readership and we can’t know the author’s intentions, what hope is there for the 21st-century reader?

“I can relate to this because…” writes one GoodReads reviewer at the beginning of a lengthy review of George Eliot’s Adam Bede. Regardless of the rest of the review, this is a remarkable statement. Eliot was born two hundred years ago and here is a woman in 2017 who can relate to her writing. There is something in literature which transcends time, a spark of humanity that can speak to people, regardless of when or where they were raised. Relatability is a powerful form of empathy, and is why the names Atwood, Woolf, Eliot, Shakespeare, Milton, Chaucer and even Virgil have survived to be remembered and re-read to this day.

We have a shared humanity with every author who’s ever existed, enabling us to look at texts centuries old and claim relatability. Because of this, the reader can act in loco parentis over a text that has been orphaned by its author. Countless academics have had their say on the entire Penguin Paperback Classics canon, it’s up to us, the readers of 2019, to forge our own ideas based on our own experiences.

But what about those contemporary texts? Anna Burns, author of Milkman which won the 2018 Man Booker Prize, has given many interviews with major media outlets giving her thoughts on her creation. To what extent can we freely interpret contemporary literature with the author still living and dictating their literary aims?

Social class, ethnicity, gender, sexuality are all factors which influence our lives and change our view of the world

While author interviews, social media posts and other media interactions can include interesting contextual information, it’s important to remember that they sold the book to you. The book is now in your hands – literally. Your opinion matters. Ask yourself why you can relate to it or not, then find examples in the text and let your ideas flow.

Every individual is unique in terms of their upbringing. Social class, ethnicity, gender, sexuality are all factors which influence our lives and change our view of the world. This means that each one of us has a unique angle from which to interpret any given text. We should celebrate differences of interpretation the same way we celebrate diversity in society – as a joyful expression of human variety.

The only misinterpretation of a novel, then, is one where there is no interpretation at all. Unless you just skim-read A Midsummer Night’s Dream and have no idea what happened in it – we’ve all been there – your impressions, whatever they were , are relevant and valuable.

So no, you didn’t misinterpret the novel. You read it in a unique way only you could. It doesn’t matter if you liked The Canterbury Tales or not, what matters is the “why.” To have an unusual opinion is far better than no opinion at all.

Comments