Rwandan genocide survivor gives testimony to Warwick students

Rwandan genocide survivor Naila Kira shared her personal testimony at the University of Warwick on Thursday 28 February, under the invitation of Warwick History Society (HistSoc).

(Content Warnings: Sexual assault, violence, death, blood)

The talk is part of HistSoc’s speaker series for Holocaust Memorial Day 2019, which bears the theme “Torn From Home”. This year marks the 25th anniversary of the 1994 Rwandan Genocide.

She gave the talk at Zeeman Building and engaged in a Q&A session with students, recounting the discrimination she faced as a Tutsi child, the process of the genocide, and how it has changed her family for life.

Naila is currently a mother of two and a social worker in the UK, who endeavours to raise awareness about genocide, introduce the topic of hate crime into classroom curricula, and “help those [who are] ‘torn from home’ in the UK”.

Rwanda was once a “hilly, very beautiful” country of 12 million people, until up to 1 million were killed in 100 days, during which the Hutu majority government attacked the Tutsi population.

Her family lost an estimate of 58 people, including her father and older brother. They “couldn’t count them all”, and to this day, they are still unsure of how many relatives they lost.

The genocide was not “something that just started in 1994”, according to Naila, who stated: “The crime started long back in 1895.

“I was born and raised in Rwanda, which was full of discrimination, even if it was because you had a long nose, you were tall – just different features.”

“It was uncomfortable to speak or sit,” she shared. “The Tutsi could not sit next to Hutus. You were treated differently in every place.”

Her father, a Tutsi, was very vocal about the discrimination they faced. Eventually, as her and her family gradually moved out of Rwanda before the genocide, her mother and father were caught and tortured.

“My family lived in fear. We didn’t know when [her father] will come back – sometimes he was gone for three days, sometimes beaten, tortured, made to drink disgusting things to remind him of who he is,” she said. “Though he was home, he was torn from his own home.”

The day before the genocide began on 7 April, Hutu President of Burundi Cyprien Ntaryamira was assassinated during the descent of his aircraft into Kigali.

“When the plane had crashed we knew that was it,” Naila recalled. “Babies were killed, women raped, parents made to rape their own children.”

Bodies were thrown into the Kagera River, which flowed into Lake Victoria in Uganda, where Naila and her remaining family were taking refuge.

Trauma doesn’t go away – you learn to live with it

– Naila Kira

Recounting her time there and how she was discriminated and perceived as an outsider, she said that the Ugandans told her to eat fish from the river instead, since “those are the bodies of your own people”.

“We had to go to the river to see if the bodies floating were our family, to bury them properly,” she shared. On 10 April 1994, her father was killed.

“My little sister in the tree saw everything when she was just 10,” she explained. “He was being cut into pieces. In Rwanda you had to pay to be shot – sometimes you pay but you won’t even get shot.

“They were chopping people as if they were chopping meat. He was chopped in a way that a human could not be chopped. He could not die – they left him there.

“But my sister could not scream. She was mute for five years after seeing it happen.”

One of the perpetrators in the murder of Naila’s father was his best friend. During the genocide, Tutsi were coerced into killing their own people by Hutu. Naila elaborated: “It was group hate. Your friends will be influenced to hate you.”

She relayed the story of her grandmother’s death, saying: “She went to church thinking it was a safe place. That was where she was killed. Her body is still there.”

Later, upon seeing the bones of those who had been killed, Naila thought, “Is this my grandma?”, and would “hug all the bones hoping that it was her, so that she can know I was there”.

When the war ended in July, Naila’s family decided to return to Rwanda. Recounting the sight, she described: “There were bodies on the street. You had to step over them. You were stepping in blood.

“That was not home anymore. That was not the place I know. I did not have a house, I did not have a memory.”

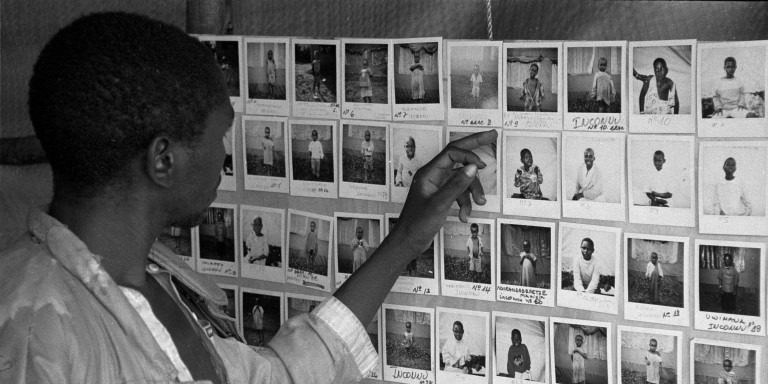

Houses were also raided and many items were stolen during the genocide. “That is how hate can change people,” Naila emphasised. “My children don’t know what I looked like as a baby because I have no photos.

“I will never have them back. I don’t have what made my home precious.”

On how her family dealt with the trauma, she shared: “I had to pretend to be strong. I was not allowed to ask, ‘are you okay?’, ‘are we going to be okay?’, ‘where is Dad?’. I wasn’t able to share anything.

“I had to internalise that – I grew up with so much hate. I hated anything that even resembled a Hutu. I hated home. I wanted to be somewhere else,” she stated, recalling how she tried to run away by telling her family she wanted to continue her pursuit of education in Uganda.

The more we hold hate the more power you are giving to the ones you hate, who will know they killed you twice

– Naila Kira

“Home is still not home. And it will never be,” she said. Although reluctant to recall the atrocities that were committed and feeling the mounting anger as the anniversary approaches, Naila said she was sharing her story “because [she has] to be the voice for those who don’t have one”.

Considering Rwanda now, Naila said: “It has since developed. Everything has changed, we’re trying to make it home. But there is still a part that can never be filled, because there is so much hate.”

When her 13-year-old son visits Rwanda, “there is something that he is expecting that he cannot get from there”. She also said: “This is what genocides do: you may think only victims suffer, but perpetrators will never live freely after – because they know what they have done to us.”

She then shared the story of her aunt, who was raped by 25 men at the age of 17 and eventually gave birth to “a young boy who was conceived with no choice”.

Describing her aunt’s hostility and shame towards her son, who she refuses to call by name, Naila said: “This is what hate does. This boy grew up knowing no one liked him. He did not belong, he looks at his mom and all he sees is hate. No one knows his father.

“Home is your heart as well. And he feels Rwanda has betrayed him.”

On how she has learned to cope with the aftermath of the genocide, Naila said: “Every day survivors survive. Trauma doesn’t go away – you learn to live with it.

“I felt the hate in me, even if I don’t act on it. It takes a heart and humanity to accept others,” she shared, and recounted how she visited her father’s murderer in prison, who showed no regret.

Afterwards, upon reflection, Naila realised: “The more we hold hate the more power you are giving to the ones you hate, who will know they killed you twice.

“If I’m holding hate in my heart, what’s the difference between me and them?”

Comments