The lengths book digitisation can take us

The rise in prominence of e-books is a phenomenon that has undoubtedly served the interests of readers and researchers everywhere. Through the digitisation of books, the cost of obtaining material for research has been significantly reduced, both in terms of time and money. This technology has also relieved libraries from the ever-growing pressure of obtaining more physical copies of academic journals and books, which can be quite difficult to track down, especially for older publications.

On a personal note, I am tremendously indebted to the online portal of Warwick Library’s website – rather than painstakingly waiting until a copy of a textbook becomes available, or spending my entire week’s budget on books, I can simply access the readings required for my course free of charge.

By making online copies available, libraries need not worry whether they have enough copies to accommodate their readers, and are able to reduce risky decisions based on predictions on the potential increase in demand for a particular book, such as at the start of an academic year. In addition, unlike physical copies, e-books are fairly invulnerable to the ravages of time, so libraries can save up as they no longer have to deal with the replacement of books in unpresentable conditions.

Looking at digital page counters cannot give out the same feelings as the experience of having the pages in your hand literally

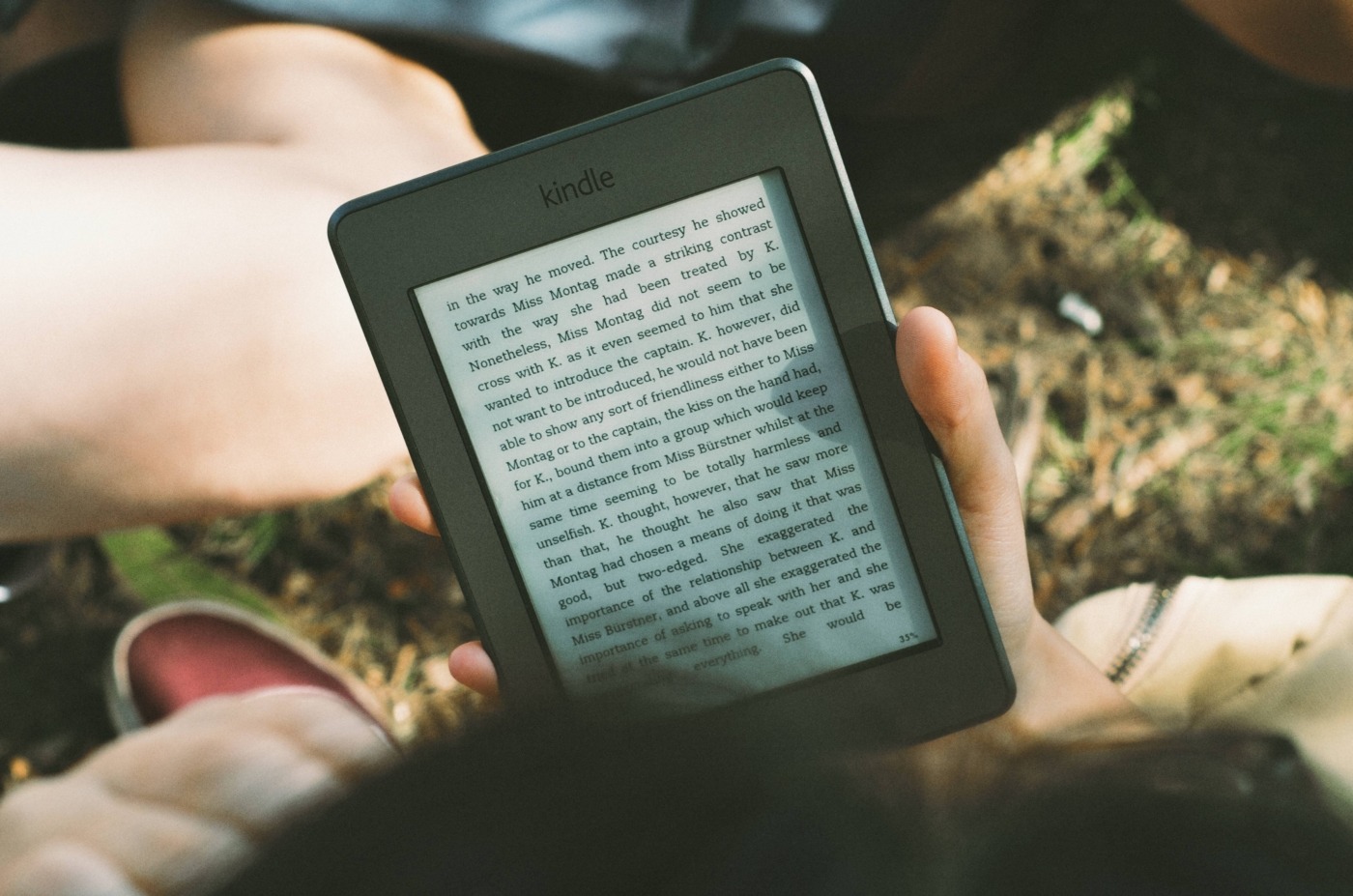

Provided with all of these benefits, why do we still feel a sense of contention when it comes to digitising books? More accurately, why are we uncomfortable with the idea that in the near future, books may be a thing of the past, and all sources of written knowledge and entertainment shifted into the digital sphere?

The limits of digitisation lie in the essence of physical books which cannot be replicated by e-books. E-book sales have been declining in recent years – in 2018, e-book sales dropped by 3.9%, while hardback and paperback sales have risen by 6.2% and 2.2% respectively, reports Observer. Perhaps this is because e-books simply cannot emulate the sensory experiences that come with reading physical books and which make readers enjoy them so much.

For one, physical books give readers a sense of progress and accomplishment as they flip through pages, with pages on the left side of the book accumulating and pages on the right thinning. This aids readers in gauging the build-up towards the climax of a story. The suspense of reaching the last few pages without yet a resolution to the plot line is something that readers eagerly devour, and e-books simply cannot offer the same kind of experience. Looking at digital page counters cannot give out the same feelings as the experience of having the pages in your hand literally.

Additionally, purchasing e-books online takes away the effort of walking into several bookshops in order to find a specific book. Personally, I have relished in sauntering around bookshops looking for the one particular edition of a book to fit my curated bookshelf. The feeling of achievement after finally picking up that one exact copy and coming home to place it in line with the rest of its series would not be available by clicking purchase on Kindle. The purchase of e-books undermines the value of effort – the feeling that you have earned your book – and thus remains undesirable for many readers.

Readers cannot run their fingers through the spines to get a ‘feel’ for a book before purchasing it in the case of e-books

Independent bookshops have been at the forefront of preserving the culture of reading on paper through the use of interesting design elements on both book covers and store design. London’s own Daunt Books, for instance, is known for its high ceilings, emerald walls and the famous arched window in its Marylebone branch. Though it may be uncomfortable to admit, appearances do matter in terms of attracting customers. Walking into a warmly-lit bookshop, being greeted with the familiar smell of books (and perhaps coffee, in the case of Waterstones with its cafes), is something that many readers associate with the whole experience of reading.

Digital books are completely detached from this atmosphere. Readers cannot run their fingers through the spines to get a ‘feel’ for a book before purchasing it in the case of e-books. Yet this is usually what captures a reader’s attention the most. It is no surprise that book covers are increasingly embellished with bevelled text and metallic accents, use bright colours and apply bold typography: examples include The Silk Roads by Peter Frankopan, the Crazy Rich Asians trilogy by Kevin Kwan, and Circe by Madeline Miller, among others. The sensory experiences linked with physical books is certainly their selling point in this digitised era.

E-books would suffice for the purposes of academic and informational reading and understanding, and they should be appreciated for their convenience and ability to democratize reading for everyone. However, for thorough enjoyment of a book, for the feeling of being transported into another world by reading, this author still rests on her belief that physical books are the way to go.

Comments