Graphic novels don’t receive the recognition they deserve

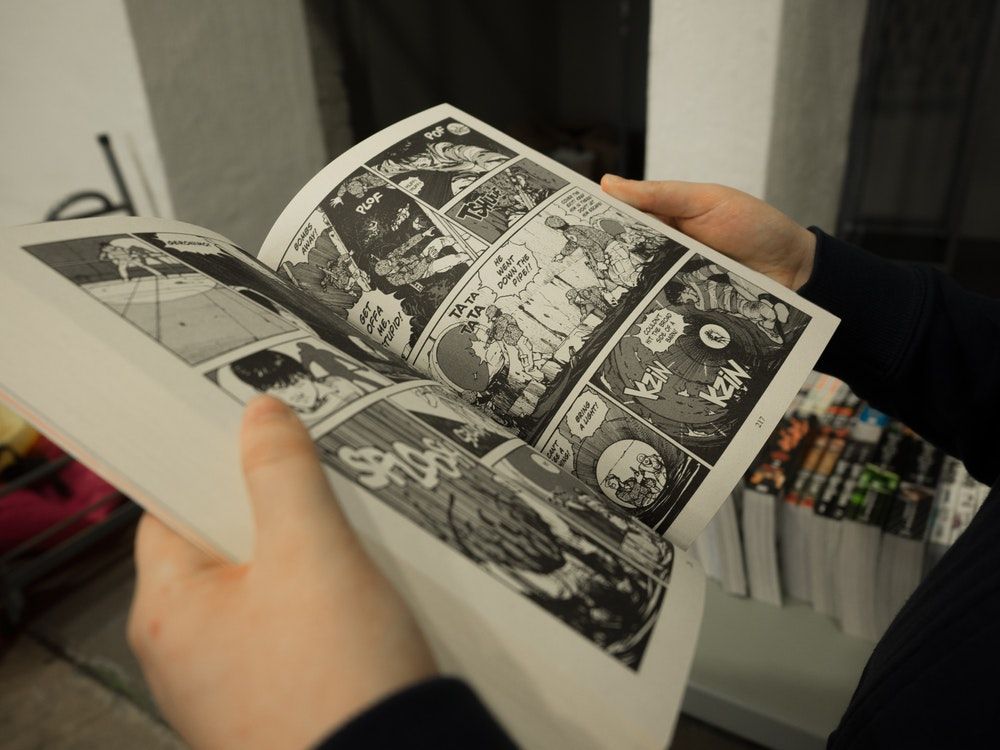

Graphic novels are to literature what hip-hop is to music and abstractionism is to art: they all attract snobbery to the extent that they are precariously contained within their ‘umbrella’ discipline. With the quantity of pictures typically outnumbering the word count, it is unsurprising that the literary status of graphic novels is often called into question. They are frequently deemed less intellectually stimulating and therefore unworthy of the esteem implied by the term ‘literature’. I believe that the hostility directed towards graphic novels is unwarranted and as a genre they deserve recognition as ‘real’ literature.

A quick browse of the Waterstones website reveals a graphic novel adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale available for pre-order. I was initially dubious as to what this visual reinvention could possibly add to an already striking dystopian narrative, but, on reflection, I realised that the literary value of a graphic adaptation does not have to lie solely in innovation.

Recreating the novel in a visual format will inevitably heighten the accessibility of a story that holds so much modern importance

Though the cynic in me is certain that profitability was the true motive behind its publication, the re-release will at the very least aid the distribution of Atwood’s prophetic story. Recreating the novel in a visual format will inevitably heighten the accessibility of a story that holds so much modern importance, raising awareness of the prevalent threat of theocracy. Atwood’s political motive is therefore preserved through its reinvention as a graphic novel, and so the new, graphic format of The Handmaid’s Tale should not be considered as demeaning, but as popularising, which is especially important for a book with such political relevance.

So, this promised, visual edition of The Handmaid’s Tale confirms graphic novels can be politically charged, seemingly aligning their worth with that of traditional novels and drama. Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis prove that graphic novels have a historical value as well. The former captures the terror of Nazism and the atrocities of the Holocaust, becoming the first graphic novel to win a Pulitzer Prize in 1992. This proves that literary accolades are not deemed exclusive for works exceeding a certain word count, elevating graphic novels to the same level of respectability granted to the other works considered for the award. Persepolis documents its author’s experience of the Islamic Revolution, revealing how autobiography is able to transcend traditional literature while sustaining its power.

But perhaps identifying the political and historical worth of graphic novels is missing the point. After all, literature is first and foremost about storytelling, and not all graphic novels are rooted in politics or history. I would argue that the appeal of escapism survives as the primary motive for avid readers, and graphic novels fulfil this expectation, simply popularising paper adventures for a more visually-captivated audience. In this sense, graphic novels serve the same function as ‘traditional’ literature, just with a slightly different execution, incorporating art alongside language. This variation and hybridisation should not be viewed as a cause for condemnation, but for celebration, evidencing the endless creative possibilities offered by literature as an art form.

These possibilities also confirm that as a genre they are capable of displaying as much breadth as drama or the traditional novel

Ultimately, graphic novels satisfy the requirements and expectations of literature. They tell stories and offer entertainment as a means of escapism, with the use of complimenting visuals in addition to language arguably making the reading experience all the more immersive, while also having the potential to serve a political purpose or provide historical insight. As well as proving that graphic novels are able to achieve the same feats as conventional literature, these possibilities also confirm that as a genre they are capable of displaying as much breadth as drama or the traditional novel.

Graphic novels are a relatively underused medium. It is likely that the extent of their expressive power remains untapped. If the success and acclaim of Maus and Persepolis are anything to go by, the genre will likely prove exceptionally fruitful. Literature as a discipline should not be presented as one of exclusivity and tradition, but as one encouraging innovation.

Comments