Bringing poetry into the public sphere

From the ancient Greek epics, to the eddas of the Norse skalds, to the confessional poetry of the second half of the 20th century, poetry has been a constant in the way we tell stories. But, to the vast majority of modern people, poetry is on its way out. Blame it on what you will: a boom in digital storytelling; syllabi that fixate on old poets whose subjects are irrelevant to a modern audience; or simply an art form that has failed to grow with humanity and reached its natural end. But one thing is for sure: poetry, as we know it, is on its way out.

Enter a new generation of poets who are changing the form of poetry to fit with modern life. Our attention spans are getting shorter – so what? Poetry was designed to relay a specific image, a specific feeling or situation, in a condensed space. Instagram poets, slam poets filling Facebook timelines, these groups have found ways of sneaking poetry back into our day to day life. Powerful images that only take a minute to absorb, before we return to the grind. And now, public poets.

The idea was to capitalise on one of the moments when we let ourselves stand still and look around us

Londoners in particular will be familiar with the concept of public space poetry. Back in 1986, Transport for London (TfL) launched a series of posters on the Tube, each displaying a poem. The idea was to capitalise on one of the moments when we let ourselves stand still and look around us: when we’re bored, waiting for a dull commute to end. This is the perfect audience for poetry. A group of people who, maybe on a normal day, wouldn’t consider reading poetry but are now desperately grasping at straws to do something, anything, other than just stare into space and dissociate for a minute.

These poems have also been used to introduce readers to new poets that they’re unlikely to have seen before: either because the poets are modern, or because they’re not on the whitewashed lists of classic poets.

In 2017, TfL launched a fresh set of six poems on the Underground, celebrating contemporary Indian poets, in a bid to represent the diversity of the city.

These initiatives are taking place across the globe. In Boston, a copycat poetry initiative to the one by TfL cropped up in 2014. In Reykjavik, certain public benches have QR codes that you can scan so you can sit and listen to a story while you rest. In Athens, spray painted QR codes led participants on a poetry treasure hunt.

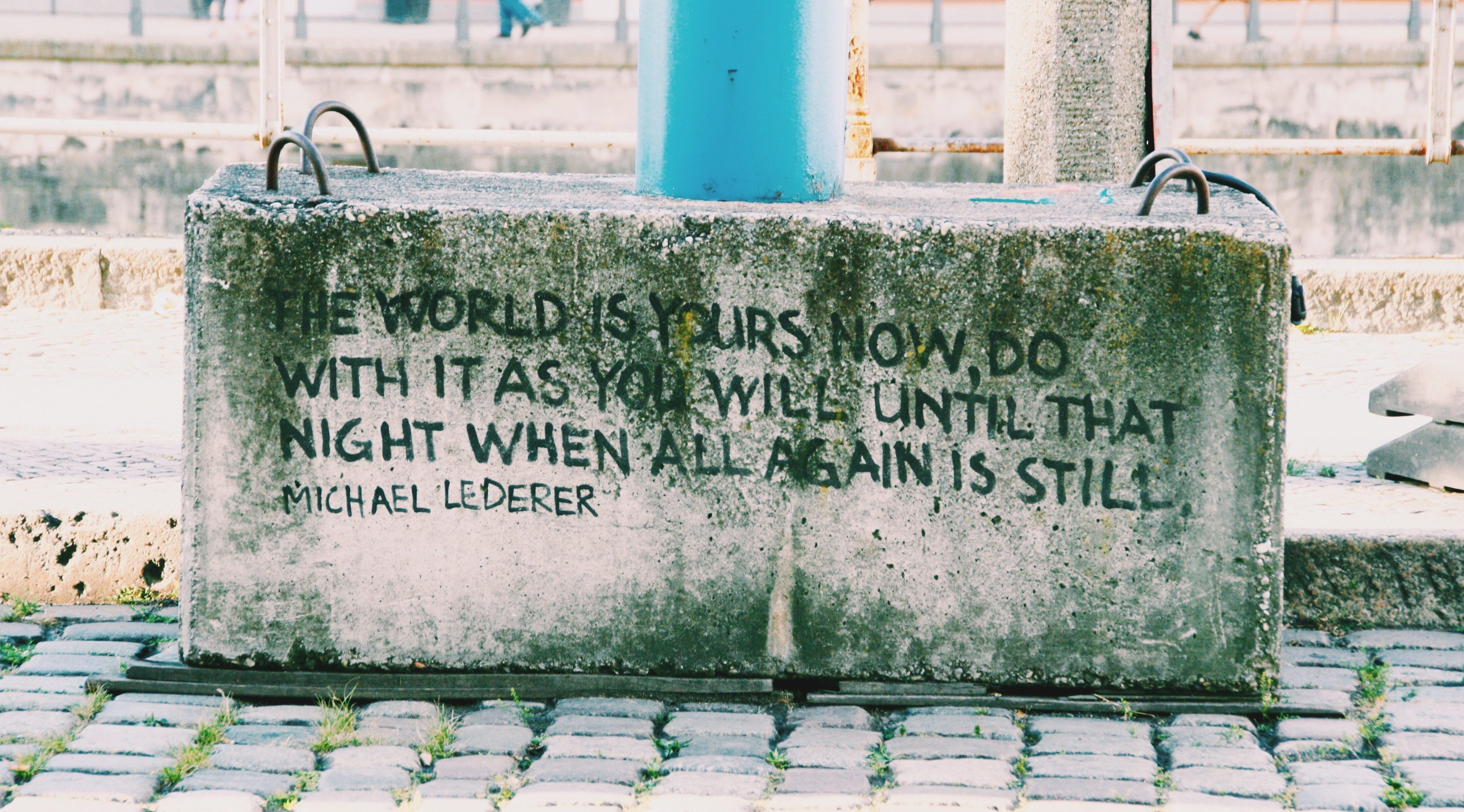

Poetry bombing is a form of presentation where poetry is written directly onto pathways, public spaces, or dropped in vast quantities from the air

Some larger, more politically inclined initiatives have taken a step further. Poetry bombing is a form of presentation where poetry is written directly onto pathways, public spaces, or dropped in vast quantities from the air.

In London’s south bank in 2012, over 100,000 poems were dropped from helicopters, with the poems in question coming from a diverse selection of contemporary poems. The event drew comparisons to a similar event in Warsaw three years earlier, where the ‘bombing’ was more profound: the project was part of a series commemorating cities that had been devastated by aerial bombing in the past. This rain of poems created a calm, almost ethereal effect in memory of a horrific tragedy.

Warwick student Jessica Kashdan-Brown is working on a public poetry project, placing poetry in the locks of the canals of Bath. The idea was born out of a seminar with the Warwick Writing Programme, led by Professor David Morley, which focused on pitching such projects.

On the subject of why these projects are important, Jess says: “Poetry is so often practiced and viewed as a solitary experience, but I feel like these kinds of projects open poetry up to a wide audience in a way that shows them that it doesn’t have to be that way, that poetry can be engaged with on so many levels, not just in an academic, literary one from behind a desk.”

The poems themselves are filled with stories of the rich history of the locks themselves

Like most poetry projects, the canal locks project relies on a modern audience that is uncharacteristically inactive for a moment: those waiting in the locks for them to drain, or people waiting on the side of locks. The poems themselves are filled with stories of the rich history of the locks themselves, histories that are often ignored. Notably, the poems have an environmental edge as well. Instead of using paints that might flake off and disturb the wildlife of the canals, the poems are pressure washed off through stencils, so that the words appear as clean rock and will, with time, disappear. Jessica is currently fundraising for the cost of the stencils on a gogetfunding page.

As Jessica puts it: “The value of this kind of approach to poetry that we’re seeing more of nowadays is, I think, most easily proven by the kind of responses and interactions they get from the communities they’re placed within. There is an incredible sense of large-scale appreciation and involvement that more traditional forms of poetry might not be able to access as easily.”

This kind of audience participation, and widescale public interest, may just be the revolution that poetry needs to last this generation.

Poetry is dead. Long live poetry.

Comments