Warwick scientists discover detailed structure of conjugated polymers

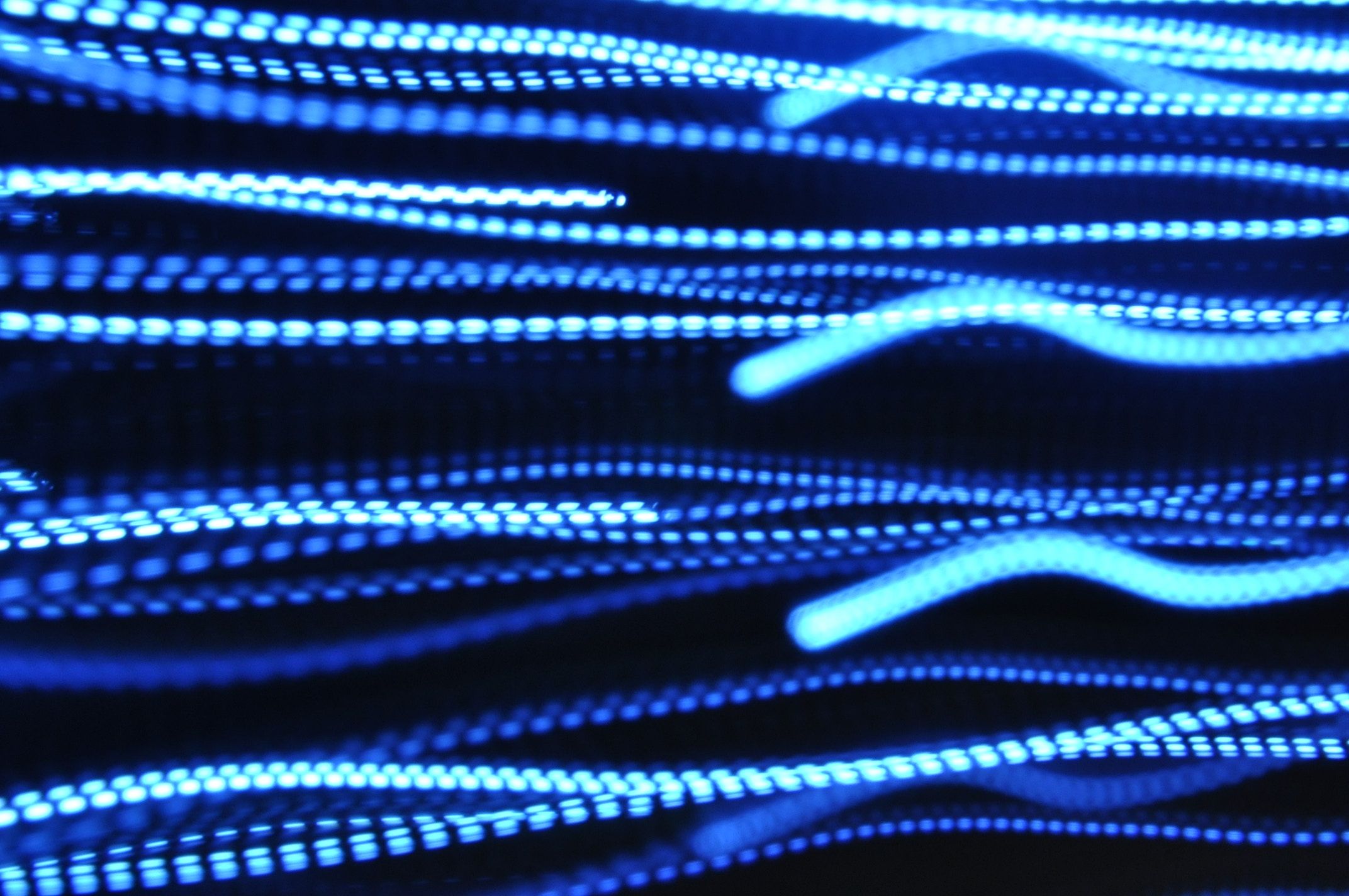

The University of Warwick is no stranger to polymer science, with many research groups at the University focusing on this area. And in a unique breakthrough by researchers at the University, we have been able to see the first ever detailed images of conjugated polymers.

Conjugated polymers are macromolecules recognised by their backbone of alternating single and double bonds. This conjugated system of pi-bonds creates a delocalised system of pi-electrons above and below the plane of the bonds. This arrangement has exciting and highly-sought after properties, as the delocalised electrons allow the polymers to conduct electricity. As a consequence, they can be used as effective molecular wires, and due to their similarities to semiconductors, can be used in applications such as organic solar cells and plastic electronics.

Conjugated polymers are macromolecules recognised by their backbone of alternating single and double bonds

And now, the first ever images of these polymers have been developed by Warwick-based scientists, led by Professor Giovanni Constantini, physicist and lecturer in Warwick’s Department of Chemistry. This discovery is significant as it allows the close structure of these interesting structures to be studied. Due to the need for good overlap of p-orbitals within the polymer structure, the order of the monomers used to create them is very important. Ideally, polymers should be constructed of monomers in the order ABAB etc. with any disruption to this sequence having detrimental consequences to the way the polymers function. This is known as a polymerisation error.

Until now, becoming aware of the precise nature and location of these errors has been difficult, as analytical techniques such as mass spectrometry raised issues of their own. In the case of mass spectrometry, which relies on ionisation techniques to detect and measure the mass to charge ratios of fragmented molecules, shorter polymer chains are disproportionally represented in spectra due to their higher propensity to be ionised.

This discovery is significant as it allows the close structure of these interesting polymers to be studied

In contrast, Costantini and his co-workers’ method for polymer observation is deceptively simple. By depositing the structures onto a surface and imaging them with high-resolution scanning tunnelling microscopy (STM), the researchers were able to detect the near exact positions of the atoms within the polymers. This method allowed them to determine that in an alternating pattern of ‘A’ monomer and a smaller ‘B’ monomer, there were defects in the polymer structure, resulting in an ‘ABBA’ pattern rather than the desired ‘ABAB’ one. In the words of Richard Feynman, “it would be very easy to make an analysis of any complicated chemical substance; all one would have to do would be to look at it and see where the atoms are.”

While difficulties were involved with depositing the intact polymers onto an atomically flat surface, the researchers were undoubtedly happy with the results. Professor Giovanni Constantini said:

“This new capability to image conjugated polymers with sub-monomeric spatial resolution, allows us, for the first time, to sequence a polymeric material by simply looking at it. Some of the first images we produced using this technique were so detailed that when the researchers who synthesised the polymers first saw them, their overjoyed impression reminded me of how new parents react to the first ultrasound scans of their babies.”

Comments