Must we read the classics?

The classics of literature: books which are destined to be studied by an Oxbridge Literature student in their long study hours and stress-fuelled nightmares. Books which are for the most part free or at the very least very cheap on Kindle. Books which will haunt every lover of reading until the day they die and quite possibly a few weeks afterwards for fear of missing out on an essential experience.

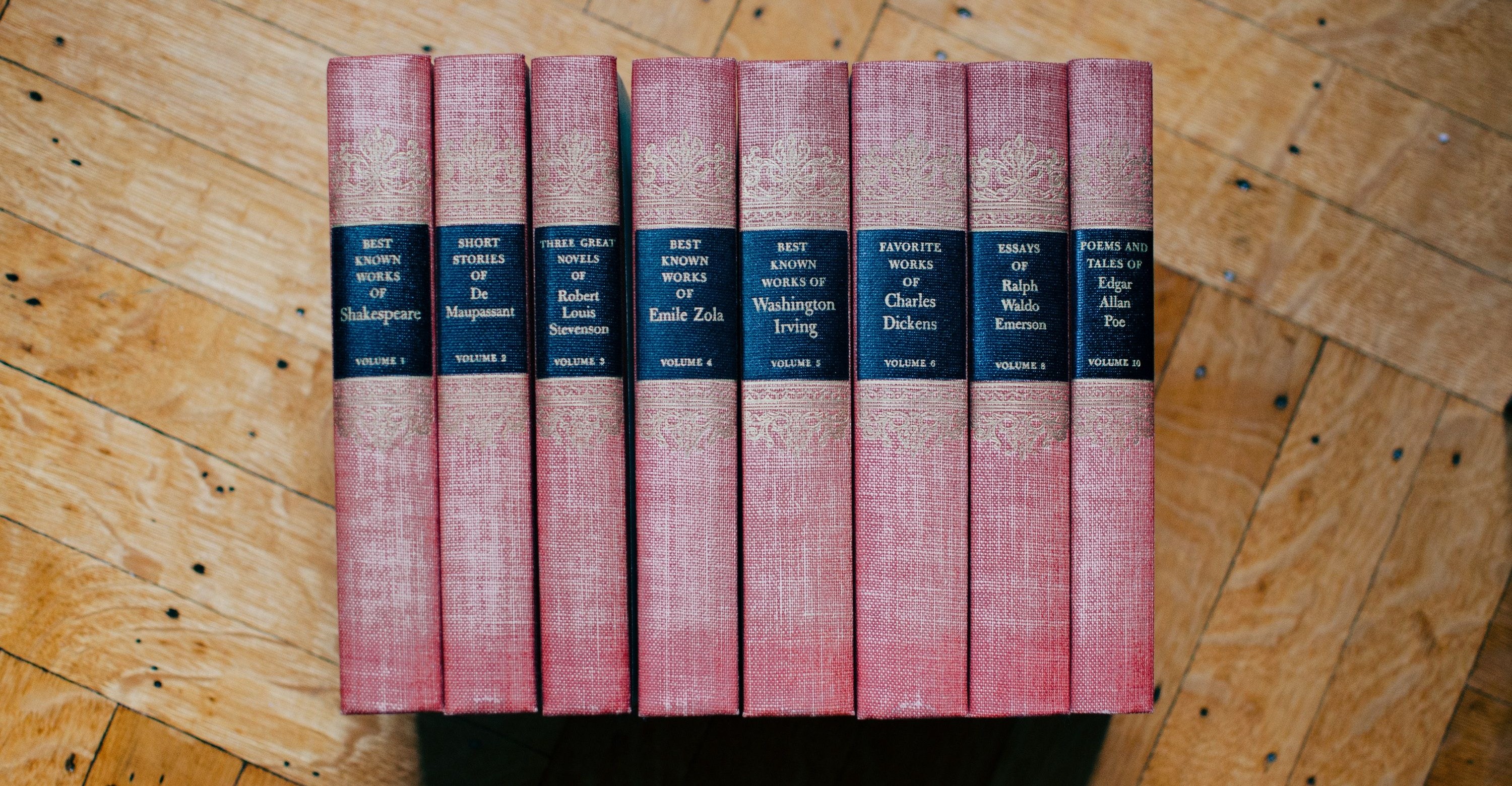

While not every list of the truly crucial books will be the same, there are usually a number of recurring authors and works. Shakespeare, Austen, Herman Melville, Of Mice and Men, Little Women and a variety of esteemed dead writers and their works lead a charge clad in Penguin publishing covers. Together they dictate that yes, they matter the most and you should read them or suffer being among the uneducated and unworthy. But should you heed their advice?

On the one hand there is no harm in reading the classics. They will not kill you unless a hardback copy of War and Peace is dropped on your head from a great height. Many of them are ‘classics’ because they have stood the only test that really matters – time. They worked when they were released, or were ahead of their time, and they still find relevance today with their themes and characters.

Together they dictate that yes, they matter the most and you should read them or suffer being among the uneducated and unworthy

The Great Gatsby was a potent mirror held up to the 1920s but it still works as a potent mirror now. Age has not dulled the beauty of To Kill a Mockingbird or The Count of Monte Cristo. Frankenstein is only more fascinating now for the genres, the interpretations, the sheer horror of all that has followed in its wake, making it a fascinating progenitor for genres the same way The Iliad is for prose itself.

When looking at a list of classics one can at least appreciate that these are, at the very least, good stories. There are lessons to be learned, stories to be dissected and characters to be sympathised with in the majority of the established ‘classics,’ and therefore they will always have value.

But should they be read at all costs? Do they deserve to be at the front of the reading list unconditionally? Yes and no. On the one hand to dismiss them is simply limiting one’s reading list and, because of all the influences they have had on books, TV, film and media, they are more important and should at the very least be understood and appreciated.

But for those teaching the classics it’s important to remember something – they’re not always going to resonate with modern young readers – and that’s okay. You cannot force resonance, you can inform people and let them work from there but the classics aren’t automatically going to work for everyone. Dickens isn’t going to speak to a 21st century audience the way he would a 19th – his characters and worlds may be intriguing but in an academic context, he will only go so far. For a student desperately reading his work for a grade, resentment and difficulty in fully appreciating his work is understandable. A recurring problem in this debate isn’t just that the classics won’t resonate purely because of a student’s reading context. Being taught on something can often remove the pleasure of exploring it on one’s own terms – though the reverse can also apply. Be patient, they may find their way into your heart when grades aren’t so apocalyptically imperative.

They’re not always going to resonate with modern young readers – and that’s okay

There is also the argument that focusing on the same number of texts means less exposure to newer authors and a more diverse array of authors as new racial, gendered and sexual experiences make their way into literature. When it comes to this argument it’s easy to embrace either the new or the old as if there is no choice but to abandon both. The truth is that it’s important to bear in mind what has survived for centuries but also to value the new and the diverse array of what’s coming into fiction now. Rather than valuing one over the other, find balance, invest in the past and the proven, and explore the new and still growing, both will reward the seeker.

As a Warwick Film and Literature student who has just finished his degree without having touched Shakespeare or any of the Classic authors but did go on many study dates with Freud, Marx and Barthes – there is so much out there beyond the same twenty or so pinnacles of Western writing, but I hope to return to the classics on my own terms. Read what you like, and remember that everything you love in the moment came from somewhere in the past, potentially a classic which may be worth your time.

Comments (1)

The problem with them being on the reading list is they easily become works read with reluctance. Of all the works we did in English, the only one I remember not being turned off was The Spirit of Jem by PH Newby.

English put me off Literature.

It took several years of post school life before I held my nose and acquired my first Penguin Classic.

* * *

Eventually I moved onto War and Peace (at the urging of a friend). Sadly I found the account turgid. I do have fond memories of Dostoevsky and Pasternak. I’ve a good collection of Penguin Classics ranging from the Upanishads, The Epic of Gilgamesh and The Rig Veda, taking in Plato, Aristotle and other works from Classical Greece, and through to hard to get works such as Juvaini’s History of The World Conqueror and The Secret History of the Mongols.

The Kindle makes access easy; there is a flip side.

It is said that few new works on the Kindle have literary merit yet these eat into business models of traditional publishers. On the basis that few reader understand good English, should we just not bother teaching it?

I self publish here’s proof