Not another Teen movie: How does the new wave of ‘coming of age’ cinema signal a new direction for the genre?

The ‘teen film’ has significantly developed since its early days. The concept of the ‘teenager’ came into its own during the 1950s, and, with this, arrived a new wave of cinema that was made for and spoke to young adults. These kids, too young to be considered adults but too old to mingle with children, finally had their own social circle and Hollywood began to exploit this exclusive demographic. The Fifties saw films such as, The Wild One, and Rock Around the Clock, which explored rebellion and rock and roll, tokens of the subversive culture of the Teenager.

As decades passed, teen films began to seep into other genres, such as comedy and horror, giving us a revamped wave in the Eighties (which is often noted as the epitomical era of young adult movies). John Hughes delivered some of the greatest examples of teenage subversion thus far, becoming the auteur of teenage angst. He explored the difficult issues that teens faced in the decade, from societal pressures and individuality to sexual relations and the future – a far cry from the nominal rumblings of social resistance in the Fifties (but still very much conservative if one is to look back on them now).

there was no room for identification, advice or comfort in the messages that these films put out

The Nineties did not see much development in the teen film. The movies played on stereotypes and, apart from producing a few iconic comedic moments, made no contribution to the social impact of this sub-genre (which had every chance of having one through its targeted demographic). Yes, young people had films marketed directly at them but that was only because they were a lucrative audience — there was no room for identification, advice or comfort in the messages that these films put out, much less, any concern for the realistic teenage experience.

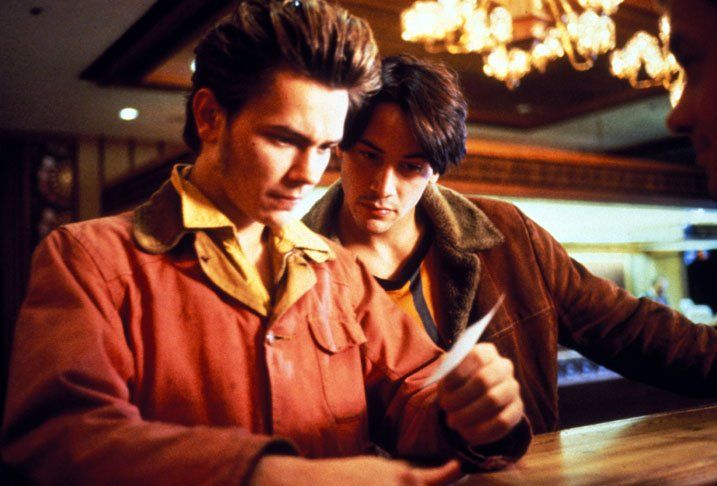

As the late Nineties moved into the 2000s, issues surrounding teenage mental health and sexuality were primarily reserved for the arthouse/indie film — think My Own Private Idaho or Bad Education. Mainstream teen-cinema was still focusing on heterosexual, white, neuro-typical characters; and spaces for mentally ill and queer POC were scarce on the big screen. Although there were characters like Damian from Mean Girls, these were caricatures and joke-machines if anything else. Young, queer kids did not have the onscreen representation they deserved, especially considering the teen movie had had over fifty years of development.

However, the 2000s. specifically, 2010 has seen a significant shift in subject matter. With the rise in popularity of Young Adult novel adaptations, the teen genre has seen more all-inclusive films than ever before. One catalyst for this was the work of author John Green, whose novels depicting hard-hitting topics such as, terminal illness; the journey from adolescence to adulthood and homosexuality have seen recent on-screen success. Books of a similar vein are rapidly being adapted for film. These novels, which have seen significant critical success and have found a solid place in the socio-cultural sphere of ‘the teen,’ are being made available to an even wider audience. The positive effect of this is evident in the recent release of Love, Simon –– an adaptation of the YA novel, Simon vs The Homo Sapiens Agenda. Unlike recent LGBTQ+ hit Call Me By Your Name, Love, Simon bears no resemblance to the brooding and seductive queer romances found in art films. Refreshingly, this new adaptation is said to be utterly average, celebrating the normality of queer teens and depicting the adolescent experience as plainly as any heterosexual teen film would. As Out magazine puts it, “young LGBTQ people can see themselves in everyday life without feeling like a tokenized piece of comic relief.”

this sort of response proves just how important it is to have a non-sexualised LGBTQ+ film aimed at young people

The impact that this film is having on young and old audiences alike is profound, with some saying — on Twitter — Love, Simon has helped them come out to friends and family and some wishing that they had had as positive a representation of queerness as this one when they were a teen. Keiynan Lonsdale, who stars in Love, Simon, has come out during the last few months and Nick Robinson, who plays Simon, has said that his brother was able to come out to him during filming. This sort of response proves just how important it is to have a non-sexualised LGBTQ+ film aimed at young people.

One of the most important features of the teen movie is representation. At an age where it may feel like the world is against you and that you don’t belong, cinema can offer a safe space for an individual to identify with characters that speak to their anxieties and insecurities. For too long, the genre has put the privileged, hetero-teen at the forefront, but it would appear that a cultural shift is starting to occur. If this new wave of teen cinema is one of all-inclusive, realistic representation then please, let it live on.

Comments