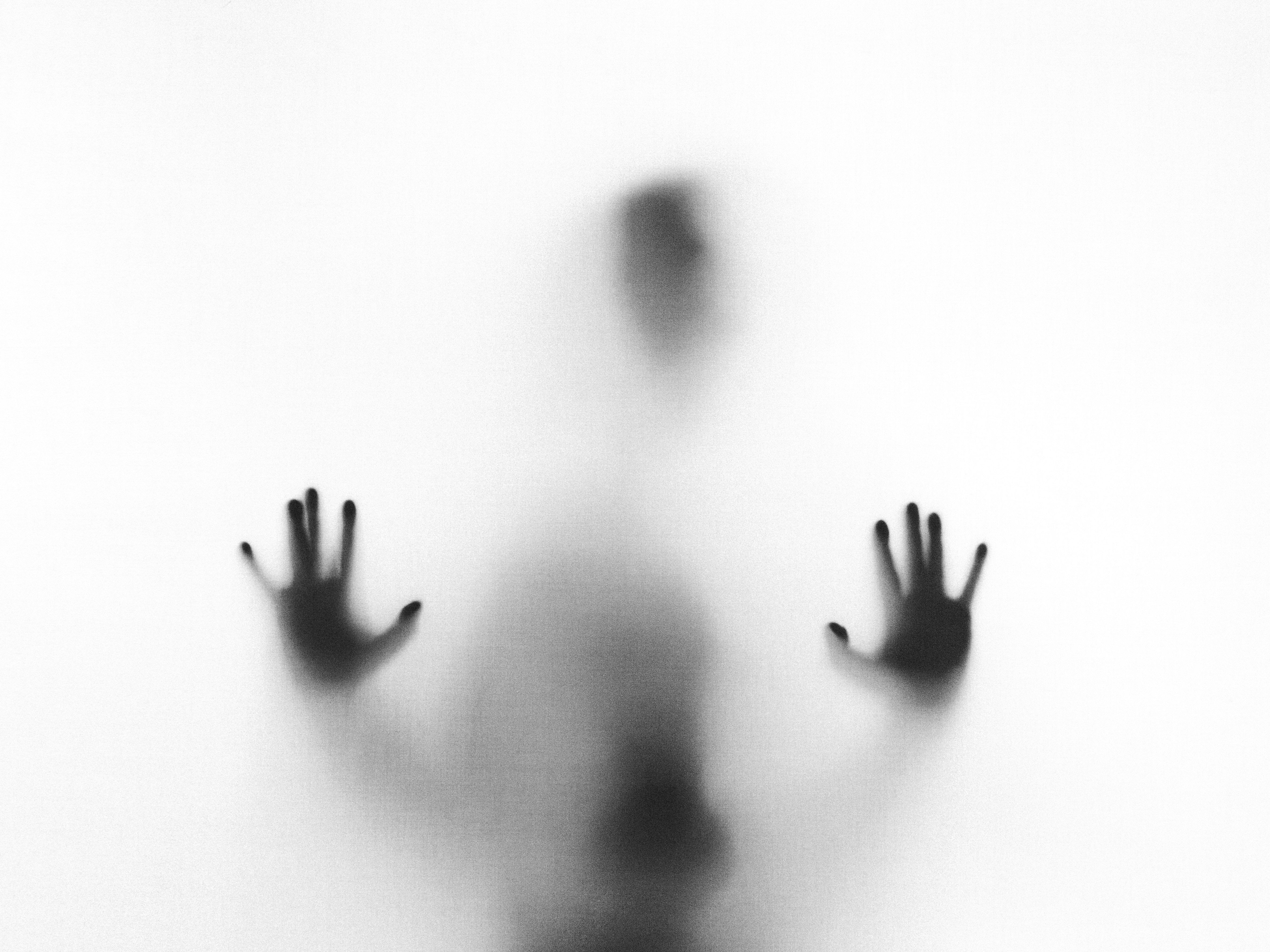

Sawing open the horror movie genre

With the recent release and box office success of Jigsaw, the eighth movie in the Saw franchise, it seems that gore-based horror — a.k.a. ‘torture porn’ — is still alive and well as a genre.

The Saw series, each film of which centres around a group of people who must participate in a ‘game’ of torture to escape traps, belongs to a sub-genre of horror, which also includes the Hostel and Human Centipede films. They focus on extreme gore and shock value and can be seen as descendants of the ‘slasher’ movies of the eighties — but they’re far more visceral.

It seems that gore-based horror — a.k.a. ‘torture porn’ — is still alive and well as a genre.

Many, like the Saw series (including Jigsaw), get consistently bad or mediocre critical reviews, but still make a killing at the box office and gain iconic pop-culture status and a place in the Western cultural consciousness. So why is it that films centred around body horror and sadistic violence have such success, and the power to captivate audiences?

Nick Lawrence, associate English professor at Warwick, sees this type of horror movie as part of an older tradition. “There’s nothing new in the taste for graphic horror – it’s been depicted in the visual, literary and performance art of most societies for millennia, and features especially in the Gothic genre”, he explains.

But the kind of horror Saw offers is certainly harder for some to stomach than gothic fiction. José Arroyo, principal teaching fellow of film studies at Warwick, thinks that “there are ways of being scared that are pleasurable, and there are ways that you just feel tortured.”

So why is it that films centred around body horror and sadistic violence have such success, and the power to captivate audiences?

Jigsaw, for Arroyo, falls into the latter category. “It was unimaginative, just bludgeoning you with things that are obviously horrifying and disgusting”, he says in his podcast Eavesdropping at the Movies. “I just felt bludgeoned by these disgusting murders, one after another after another.”

Is there a distinction, then, between movies that scare and those that “bludgeon” you with body horror? Lawrence argues that the answer lies on the distinction between terror and horror — the former of which “is a function of fearful anticipation” and the latter “the realisation of terror in material form”. According to Lawrence, this realisation “has always had an element of the viscerally or biologically repulsive about it – think of Frankenstein’s monster, composed of dead matter.”

The horrors of the Human Centipede. Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Jigsaw definitely has this element of the biologically repulsive — in fact, it could be argued that this is the main draw of ‘torture porn’ as a genre. The visceral and biological aspect of horror has the power to fascinate and captivate viewers. It’s easy to attribute that to the rush of adrenaline that comes with on-screen shocks, and an accompanying feeling of pushing and transgressing boundaries.

But Lawrence suggests that this reaction has evolved into something different for the contemporary horror viewer. “The body is continually being transformed by medicine and technology”, he says. “In a strange way, the original horror function…has morphed into a weird form of reassurance — that we’re still fragile, responsive, mortal beings.”

Jigsaw definitely has this element of the biologically repulsive — in fact, it could be argued that this is the main draw of ‘torture porn’ as a genre.

So it could be that Saw and the torture movie still endures because they show viewers living in an increasingly post-human world that they are still made up of living flesh, startlingly susceptible to the forces of chainsaws and head-crushing devices.

But perhaps the genre is still relevant in a more chilling way. Arroyo sees Jigsaw in particular as “a Trumpist film”, saying “there’s a fascist element to the whole film; you follow the rules or you die.” The games depicted in Saw depict dire consequences when the characters try to defy the villain Jigsaw’s authority, and suggest that perhaps these victims deserve their punishment.

For good or bad, torture movies endure in cinemas and in the cultural imagination, part of a horror tradition of fascination with the grotesque. Like Frankenstein’s monster, this genre has been given a new life: reflecting both our anxieties of a technological world where humanity is in danger of becoming obsolete, and an increasingly punishing and intolerant political climate. Perhaps among all the gore of the torture flick, society is also slashed open, and the gruesome insides revealed.

Comments