An Actor Repeats: Ian McKellen’s King Lear and the Risks of Revival

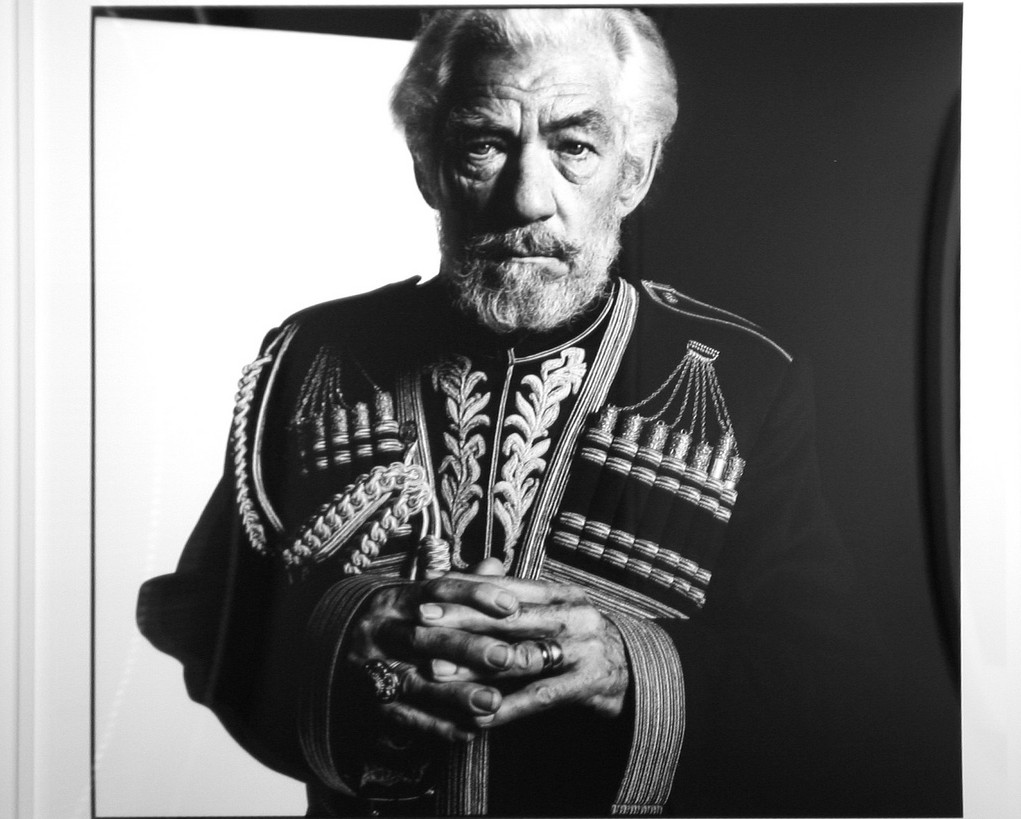

To the modern actor, the notion of repetition is a frightful one indeed. To the Shakespearean actor, however, it is a lifestyle; one that has kept several of history’s greatest players afloat in their advancing years. The subject of artistic repetition was very much on my mind nearly a month ago upon witnessing Ian McKellen’s second King Lear in Chichester, the only Shakespearean role to which he has thus far returned. Given the enormous success of McKellen’s first attempt at the RSC in 2007, it begs an obvious question: why should any actor wish to return to a role that they have already conquered? Does it stem from a desire to relive former glories and capitalize on an already successful interpretation, or to improve upon a performance with which they (and indeed the audience) were plainly unsatisfied?

To the Shakespearean actor, repetition is a lifestyle

The former could be said of many of history’s more celebrated thespians, including Henry Irving (who played Shylock 1000 times over twenty-six years and died in the role), Johnston Forbes-Robertson (who gave his final Hamlet in a 1913 feature film at the age of sixty) and Sarah Siddons (who performed Lady Macbeth for the last time in 1812 after 25 years of continued acclaim). The latter, however, can be said too, as countless actors have redeemed themselves with the aid of a second (or indeed third) chance. Patrick Stewart, for example, gave a disastrous, immature Shylock at Bristol in 1963 (‘I should have been arrested for overacting, if not for racism’), only to be reappraised for his energetic, cruel turn at the RSC in 1978 and finally lauded for his performance in Rupert Goold’s brilliant, Las Vegas-bound Merchant in 2011. Even Sir John Gielgud, whose original 1930 Hamlet was hailed by critic James Agate as ‘the high water mark of English Shakespearian acting in our time’, felt that there was room for improvement, approaching his final performance in 1944 from an entirely new angle and causing Agate to reiterate that ‘this is, and is likely to remain, the best Hamlet of our time’.

However, while many actors have profited from the opportunity of revival, others have succeeded in damaging both their reputations and the memory of their original grandeur. Peter O’Toole and Richard Burton’s 1963 and 1964 Hamlets in London and on Broadway were unfavourably compared to their original performances (Bristol in ’58 and London in ’53 respectively), while Michael Gambon’s second Othello at Scarborough in 1990 caused such controversy that it brought an end to white actors playing the role in blackface.

Other actors have succeeded in damaging both their reputations and the memory of their original grandeur

If Gambon’s failure was one of timing, the same, it pains me to say, could be said of Ian McKellen’s second (and seemingly final) King Lear. In 2007, McKellen gave a fiery, near-operatic performance as the crumbling despot, leaving the audience in no doubt of his ability to control ‘the sacred radiance of the sun’. A near unreachable watermark was set, one with which any actor would struggle. And yet a decade later, seemingly undaunted by the monument of his own creation, McKellen announced that he would return to the role, citing ‘unfinished business’ as his primary motive. Disappointingly, the resultant production by Jonathan Munby was characterised not by the poetic grandeur that Trevor Nunn’s enjoyed but rather a growing sense of bitter anti-climax, riddled with dramatic missteps (the decision to send the ancient Lear into war with khakis and a pistol continues to astound me) and contrived direction (the ‘Reservoir Dogs’ approach to the eye-gouging scene was played childishly at best). It was centred, furthermore, on a performance that in its desperation to distinguish itself from its more tempestuous predecessor, only served to contribute to an overall feeling of lifelessness with which the production was terminally plagued. Herein lies the danger of returning to an already successful role: in the shadow of a definitive performance, a truly appeasing revival is all the more difficult to achieve. Such is the curse of reputation, and McKellen’s is a high one indeed.

Comments