The underrated value of non-fiction

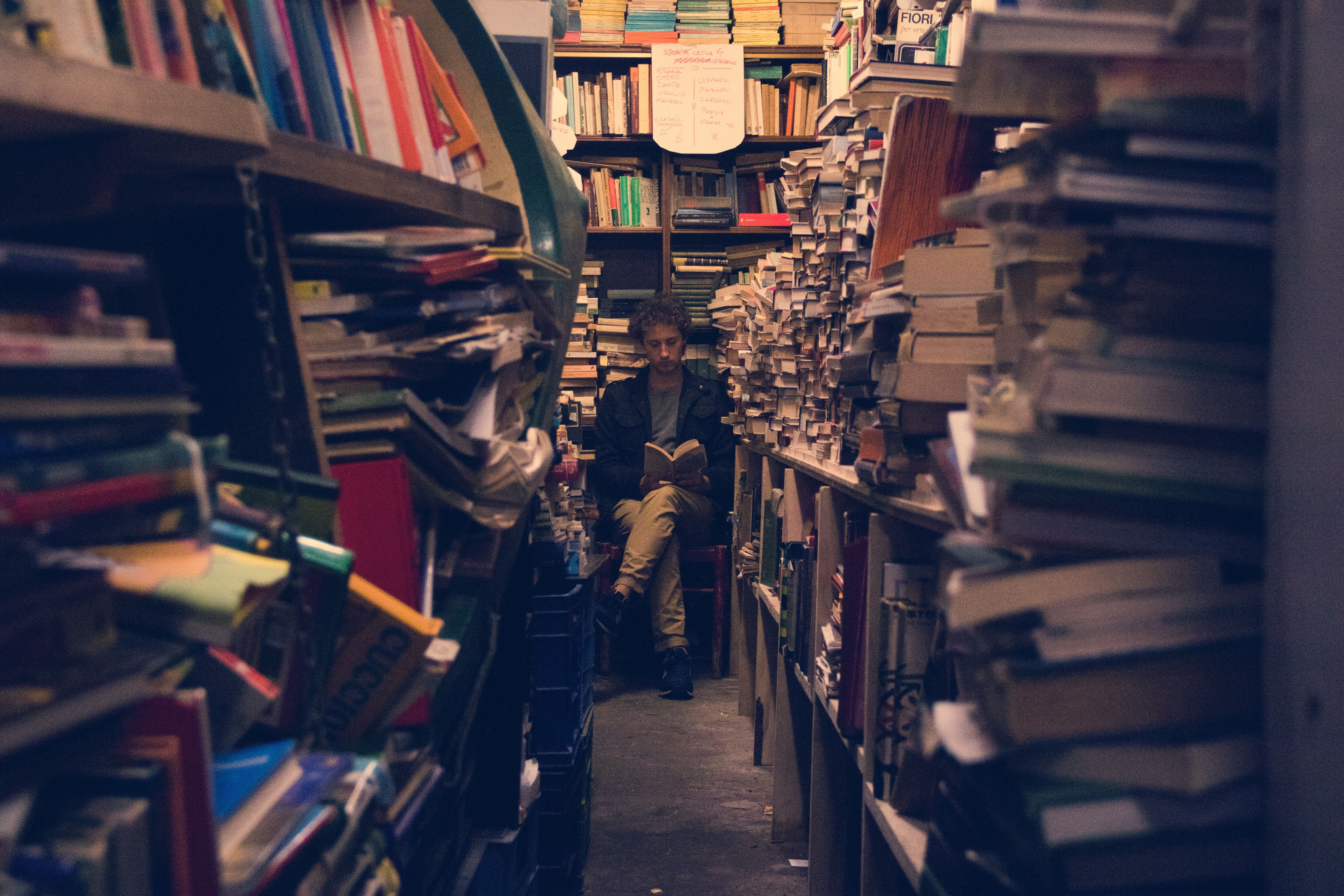

If we walk into any bookshop today, we’re faced with a huge array of reading material to delve into, the shelves encompassing whatever our hearts desire. Having recently moved away from fictional novels and instead beginning an exploration of the genre of non-fiction, I’ve found myself feeling as though the experience of reading non-fiction is more rewarding to me than reading fiction can be. Having largely read fiction during my lifetime, most recently influenced by the infamous ‘wider reading’ of A-Level English literature and now an arts degree, perhaps my feeling is merely a personal reaction to enjoying a different style of writing – but I can’t help feeling there’s some deeper truth to this impression.

By the end of their respective books, the readers of non-fiction feel as though they have gained more than the fiction readers…

They say that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and it definitely holds true for reading. Reading can be an extremely individual experience, so what one person seeks to get out of reading – and what they define as a worthwhile or valuable reading experience – will undoubtedly differ from the next. For some of us, it’s about losing ourselves in elaborate descriptions of fantasy worlds to help us escape our own, whereas for others the pleasure from reading is driven by learning something new from a book and widening their perspective of the world. Nevertheless, it seems that reading non-fiction lends itself to utility in a way that fiction doesn’t. Trawling through numerous bookshops’ websites, I was amazed at the volume of self-development books, books about the mind, body and spirit and the seemingly never-ending subcategories thereof. It seems people really will write a book about almost anything, but which you may not ever stumble upon if you aren’t specifically looking for it.

Most non-fiction books are more obviously written specifically for purpose, one which drives us to seek out that book in the first place, whether it’s learning the practices of a religion, how to be more organised or healthier. If you want to read a novel, you can potentially afford to be less specific in which book you’re looking for – while everyone has genre preferences, it’s possible to walk into a bookshop intending to buy Pride and Prejudice and come out with The Da Vinci Code. Surely, then, it wouldn’t be that ridiculous to suggest that by the end of their respective books, the readers of non-fiction feel as though they have gained more than the fiction readers, because they likely set out to gain that something in the first place? We’re probably all well-acquainted with the feeling of reaching the final words of a gripping novel and being left with an open mouth thinking, “what now?”, but I can’t imagine that this happens all too frequently with non-fiction.

As students it’s easy to feel pressure to be reading things which are intellectually stimulating and useful, and a non-fiction book about a real world topic seems the way to do this

Is it a case of there being certain books which we feel are more valuable to us, or rather that they are merely less guilt-inducing? I often fall victim to this myself, and admittedly it’s probably what influenced my decision to read Orwell’s 1984 this summer as opposed to the beachy chick-lit, which often receives a bit of stick, that I could have chosen. As students it’s easy to feel pressure to be reading things which are intellectually stimulating and useful, and a non-fiction book about a real world topic seems the way to do this. 1984 is fiction, yet its underlying political message appears to render it more valid than, say, Harry Potter, even though both novels follow made-up people in made-up worlds.

I’d invite anyone to try and come up some kind of Venn-diagram or spectrum for deciding what constitutes a worthwhile read, but the subjectivity of how we choose our reading material seems to prove how difficult this is. Essentially, no book is better than the other, and the range of material out there reflects this; after all, there’s a reason why you don’t walk into Waterstones and just see one section.

Comments