Philip K. Dick’s Electric Dreams

With its immense acting and masterfully constructed dystopias, anyone missing Black Mirror will be at ease with this sci-fi masterpiece. Whilst some episodes certainly shine more than others, the ease with which Philip K. Dick’s Electric Dreams creates dystopias and superbly acted characters to go in them is amazing.

Generally the genius of any film or television piece can usually be seen in its first shot. How much we can learn from a mere few seconds can often convey more meaning than some pieces manage in their entirety. ‘The Hood Maker’ encapsulates this truth perfectly. The very first frame creates a sense of absolute peace: the calming sound of beautifully clear water and the uniform symmetry of the underwater plants we see engenders a perfect serenity in us. As the camera pans the scene grows more idyllic; nothing is quite as quintessentially peaceful as a father and son fishing together. The soundtrack (which is immense across the series might I add) is stripped back: it adheres to the John Williams/Jaws school of using simplified music to elicit raw emotion in the viewer – in this case that of utter peace. The beauty of this scene is enchanting. Yet as the camera pans back there is an alien presence: seeing a woman fully dressed yet knee high in water is odd. She is out of place with this serenity, as is her aghast facial expression.

From the very beginning a mood of unease is created in the audience. Even the steam rising from a wok in the next shot serves as a symbol for the pressure and metaphorical heat of a society on the brink of a civil strife that explodes before the viewers eyes in this episode. For me no other television show has ever epitomised as much the aspiration to make every frame a painting.

Electric Dreams then constructs eerie dystopias on both macro and micro scales to perfection

The construction of a dystopia in the series is something truly to marvel at. In ‘The Hood Maker,’ a world predominantly framed with a 70s style provides something familiar for a modern viewer but not at all comforting: there is something alien about this world. A place in which all shots display the world from the people’s level, not some distant aerial zoom shot. In this cityscape, things seem too crowded, there are no roads or infrastructure, and everything is ramshackle. It isn’t some far flung distant land but neither is it any world we would recognise. This perverted familiarity creates a template more unsettling than any other. Add to this an oppressive regime and a divisive split in society and we get a dystopia amazing not only in its connections and lessons to our world but also in and of itself.

The futuristic dystopia of ‘The Impossible Planet’ takes a differing approach, introducing a completely distant universe in which we are encased in a space bound world of metal. It’s an emotionless, empty place, that makes us as viewers ever more sympathetic to the disaffected protagonist Norton. There is certainly something massively disturbing also in the universe of ‘Crazy Diamond,’ a world where with aggressively encroaching coastlines and food mysteriously unable to stay fresh; nature seems to be rejecting mankind. The future dystopia of ‘Human Is’ is not only disturbing for its barren emptiness, but also the stratification of class reflected literally in how close to the surface of the planet and thus breathable air your housing is, creating a material allegory for the injustice of such hierarchy, in a similar style to J D Ballard’s High-Rise. All these dystopias are not only brutally disturbing emotionally for the viewer, but also provide messages that each and every viewer can still connect with.

Though set in reality, ‘The Commuter’ manages to perfectly capture idea of a pristine world hiding its true dark nature in the town of Macon Heights. We feel as engrossed in this utopia as Spall’s character does, and the cinematography allows us to only see the imperfection of this place on his final visit, when the protagonist makes the realisation himself. Suddenly we see that the perfect houses that we had only ever seen from the front have no substance: they are quite literally just that front. Even a seemingly happy scene, an engaged couple celebrating, becomes darker as it plays out verbatim on each of the protagonist’s visits. Electric Dreams then constructs eerie dystopias on both macro and micro scales to perfection.

Each episode is unique, mysterious and multifaceted enough to allow us to derive meaning ourselves

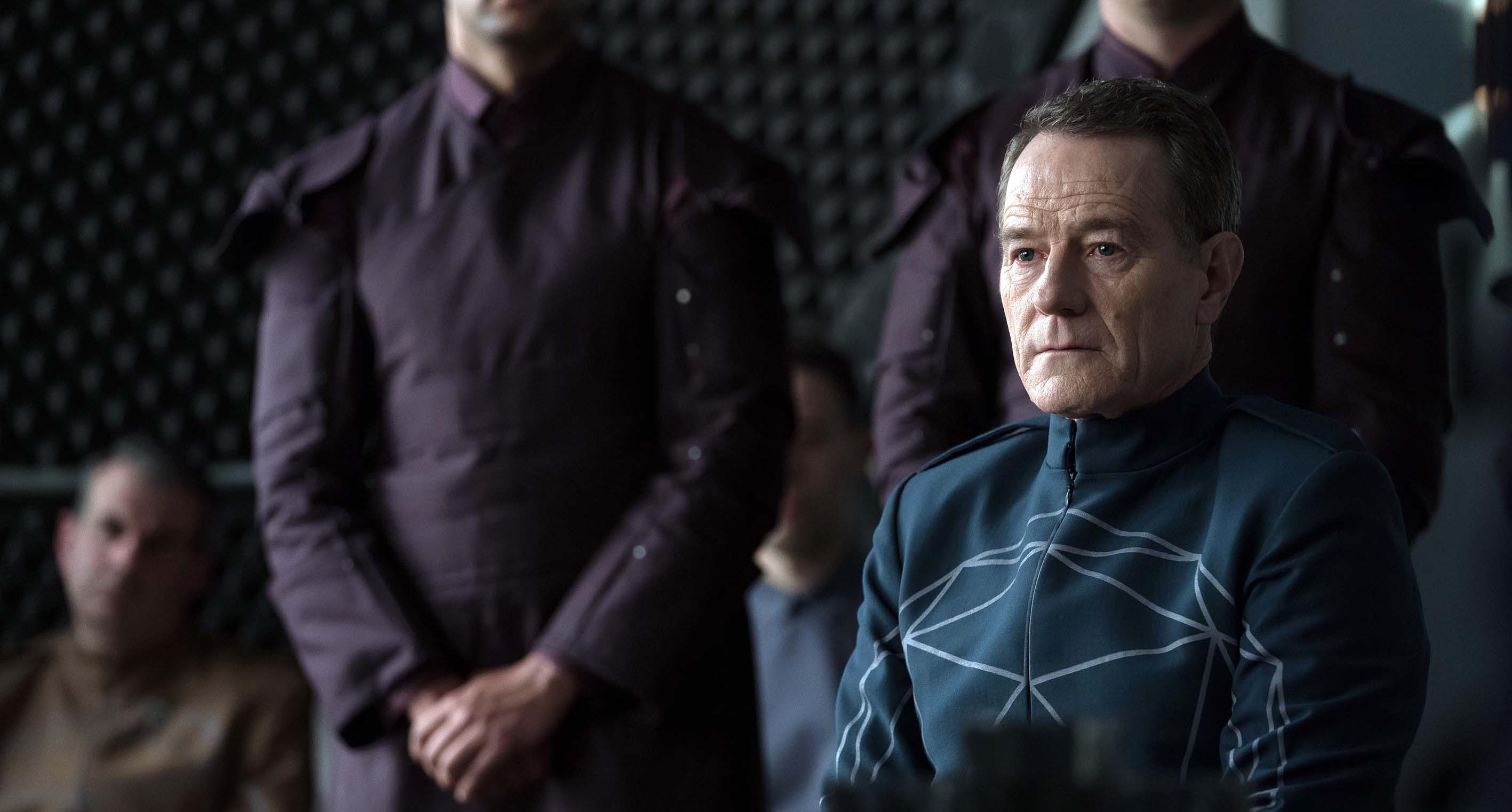

The acting in this show also proves to be utterly immense. Despite writing problems in ‘Crazy Diamond’ and ‘Real Life,’ the masterful acting of Steve Buscemi in the former and Terence Howard in the latter helps make up for this. In ‘Human Is,’ Bryan Cranston expertly depicts a chilling character change: rather than a descent into darkness, he manages to portray someone who returns from a traumatising mission more kind and serene then he was before. Conceptually this is massively disturbing, as it flips the conventional, expected change seen in a soldier returning from war onto its disturbing head. The capacity to display raw distress in its purest form is also remarkable. Timothy Spall displays the pain of a man who realises the terrible human cost of his happiness to such perfection it brought a tear to my eye. Holliday Grainger in ‘The Hood Maker’ so aptly captured the flurry of vivid emotions that would affect a telepath as they read someone’s deepest darkest thoughts that I almost believed her to actually have superpowers. Whilst Richard Madden’s performance and ability to play off her makes the episode even more engaging for the viewer. All in all, with a top class cast, you get what you expect – top class acting.

One might expect me to tell of the lessons each episode teaches viewers in this piece, but the very genius of Electric Dreams comes from the fact that the lessons each person perceive in an episode are unique to them. It doesn’t dictate some monotonous moral message – each episode is unique, mysterious and multifaceted enough to allow us to derive that meaning ourselves. I chose to hope as ‘The Hood Maker’ came to a close that Honour would open the door for Ross, as did I hope that in ‘The Impossible Planet,’ somehow Norton and Irma managed to escape to the beautiful world of Irma’s earth born grandparents and in ‘Human Is’ Cranston’s character had somehow discovered his humanity, but these weren’t absolutes. They reflect more on my romanticism, as each person’s interpretation reflects more on them than on the show itself. In that way, Electric Dreams is even more of a ‘black mirror’ than Black Mirror itself is.

Comments