Who won the 2017 Nobel Prizes?

Arguably one of the most recognised outputs of Sweden, the Nobel Prizes give top authors, scientists and peace promoters the recognition so many deserve in the form of the most prestigious prize on earth. Divided into five categories, the Nobel Prizes were formulated by an industrialist named Alfred Nobel who stated in his 1895 will that his $260 million fortune was to be given out “to those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit on mankind”. Nobel set some guidelines for the awards; the recipient must be alive, the peace prize should be handled by Norway not Sweden, and the award can be shared by a maximum of three people. The latter causes a lot of controversy to this day, particularly within the scientific categories, where collaboration is at the heart of every discovery.

Nobel Prize in Physics 2017

LIGO/VIRGO Collaboration with one half to Rainer Weiss and the other half jointly to Barry C. Barish and Kip S. Thorne for decisive contributions to the LIGO detector and the observation of gravitational waves.

Our knowledge of the Universe is minute compared to its size. Finding new methods which allow us to find out more from earth about what is going on in the Universe is of the upmost importance, and in this case, worthy of a Nobel Prize. First detected on 14th September 2015, but predicted by Albert Einstein some 100 years before as part of his general theory of relativity, gravitational waves can provide scientists with information about events which have happened over a billion years ago.

The waves themselves are ripples in the fabric of space-time, which occur when extreme events, such as the orbiting of massive bodies, happen. The ripples then travel at the speed of light through the universe, providing insight into the bodies from which they originate. The ones that were detected by LIGO (the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory) in the USA were from a collision of two black holes approximately 1.3 billion years ago.

Over 1,000 researchers collaborated on this project, representing 20 countries, but only 3 could be picked to receive the Nobel Prize…

Over 1,000 researchers collaborated on this project, representing 20 countries, but only 3 could be picked to receive the Nobel Prize. One of those, Rainer Weiss, was working on the detection of gravitational waves back in the mid-1970’s, and had developed a laser interferometer to curb the background noise. Along with Kip Thorne, they were then convinced that it was possible to detect them, and 40 years later they defied Einstein’s statement that gravitational waves would never be detected.

This Nobel Prize hits closer to home than most. Researchers from the University of Warwick are currently in La Palma operating the GOTO (Gravitational-wave Optical Transient Observer). Officially opened on 3rd July 2017 in the Roque de los Muchachos Observatory of the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canaries, this ground-breaking telescope can detect the optical signatures of gravitational waves. Being able to associate the waves detected to parts of the electromagnetic spectrum will allow astronomers to discover the source of them and aid this revolutionary insight into the distant Universe.

Image: LIGO Detector, Kanijoman/ Flickr

Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2017

Jacques Dubochet, Joachim Frank and Richard Henderson for developing cryo-electron microscopy for the high-resolution structure determination of biomolecules in solution.

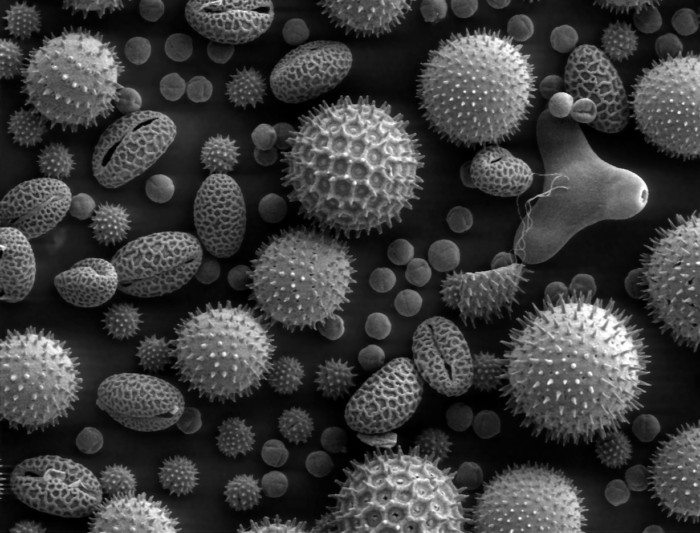

Scaling down from the huge events in the universe being explored in the Nobel Prize in physics, the Nobel Prize in Chemistry is awarded to a method used to observe objects on an atomic scale-electron microscopy. Previous methods to do this proved detrimental to the living organism being observed, damaging it before scientists had a chance to determine anything, but cryo-electron microscopy “simplifies and improves the imaging of biomolecules” moving biochemistry into a new era.

British scientist Richard Henderson was responsible for enabling an electron microscope to “generate a three-dimensional image of a protein at atomic resolution”. Prior to this, the electron microscope was only seen to be useful for imaging dead matter, as its powerful beam can penetrate matter. Joachim Frank managed to develop an image processing method which sharpened the previously fuzzy 2D images to a crystal clear 3D visualisation, making the electron microscope more useful. Jacques Dubochet finished off the trio’s work by introducing water to the mix. After observing the evaporation of liquid water in the electron microscope’s vacuum, Dubochet discovered that by rapidly cooling the sample prior to observation, the water would form a solidified liquid shell around it, allowing it to retain its original shape in observation.

This highlights the importance of collaboration within science, and that information exchanged across boundaries can potentially lead to some of the best ideas.

Collaboration was key for this method to be fine tuned to its optimal ability, which was achieved in 2013. Since then its capacity to produce visual maps of biological systems has proved to be revolutionary in multiple fields. Cryo-electron microscopy has already been used to observe the Zika virus, providing information to aid a vaccine for it, and has been postulated to be key in advancing cancer drug development.

The only Brit in this trio of Nobel laureates, Richard Henderson had a typically English method for his success. “Having a tea break was very important” to his work as it allowed him to have “discussions from across disciplines”. This highlights the importance of collaboration within science, and that information exchanged across boundaries can potentially lead to some of the best ideas.

Image: Electron microscopy image of pollen, Dartmouth College Electron Microscope Facility / Wikimedia Commons

Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2017

Jeffrey C. Hall, Michael Rosbash and Michael W. Young for their discoveries of molecular mechanisms controlling the circadian rhythm.

Most of the time our body runs like clockwork, easily adapting to different times and situations as they arise. The fact that it runs so smoothly is partly down to our internal circadian body clock. For many years scientists have pondered the question as to how the internal clocks of humans, plants and animals work in synchronisation with the Earth’s rotation, and the three recipients of this Nobel Prize have found out exactly that.

Their work involved using fruit flies to obtain and isolate the gene which controls their daily mechanisms. Once found, they were able to show how it encodes proteins overnight to then be distributed throughout the day. Taking this research further they were able to discover additional proteins which are formed and used in conjunction with the others cyclically over a 24 hour period to maintain the daily biological rhythm.

Our body clock helps with the regulation of hormones, behaviour, body temperature, sleep and metabolism…

Their discovery is a huge step into understanding more about the complexity of our species. Our body clock helps with the regulation of hormones, behaviour, body temperature, sleep and metabolism. When there is a change in the daily schedule of the body, such as jet-lag, there is a negative affect on our wellbeing. Misalignment of our internal rhythm and external routine could lead to an increased risk of various diseases.

Work from numerous scientists dating back to the 1970s was used to help with this breakthrough. However, one recipient of this prize has previously caused a stir within the science community. Jeffrey Hall, mainly based at Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts, left science 10 years ago due to a “lack of funding and an increase in institutional corruption”. After a series of rejections for more research money, Hall spoke of his love for his “little flies” and claimed that he and his colleagues could “continue to interact with them productively”. Jeffrey’s inclusion in the line-up again brings to light questions about the way in which scientific research funding is allocated, and this will not be the last time this debate will be had.

Comments