The future of journalism? An interview with Compass News

Matilde was late for our interview; one of her meetings had overrun. This isn’t really a surprise, considering her incredibly busy lifestyle. A typical day, according to her, consists of “talking to students, planning launches, testing the product, investors’ meetings, publishers’ meetings…I’m in the office from 9:30 until 10, including weekends obviously.”

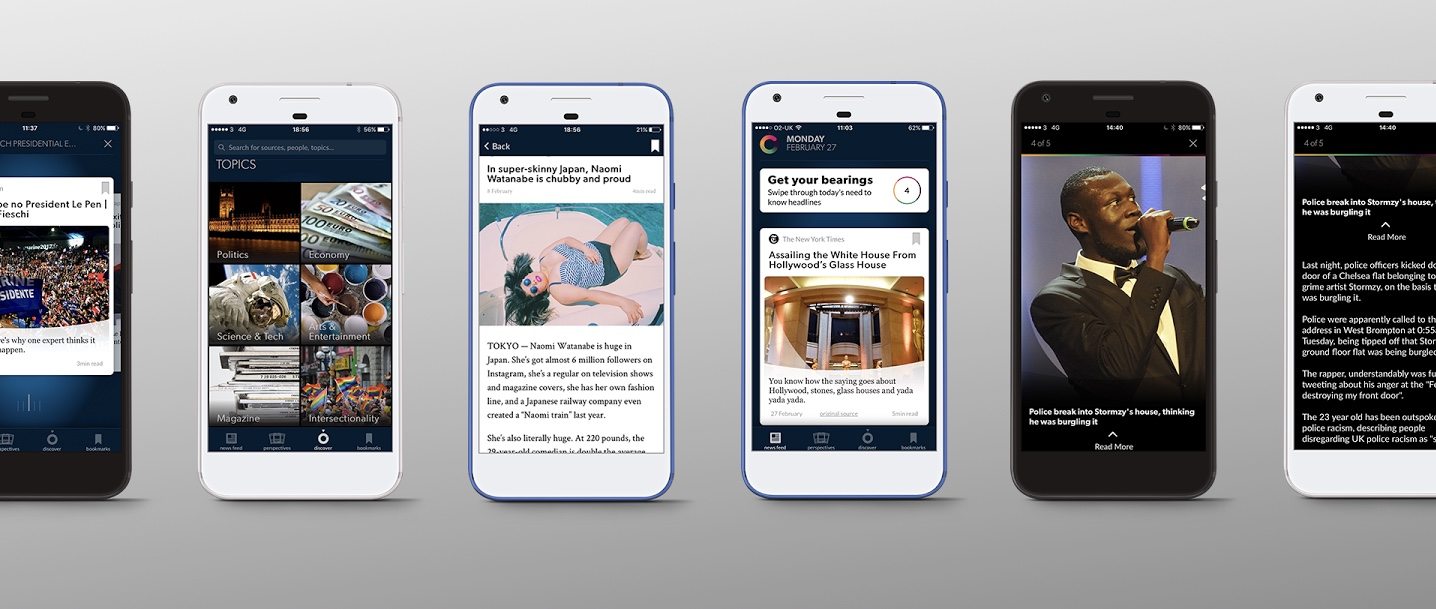

A year and a half ago, Matilde, Mayank, and Felix decided to co-found Compass News, “the Spotify of journalism”. At the time they were merely students—Matilde was doing a Masters at the LSE and Mayank and Felix were studying at Oxford—passionate about journalism and concerned with its future. Now, they have over 6,000 users across five UK Universities, and are soon opening up to other institutions in both Britain and the US. “It’s going incredibly well, strangely enough”, Matilde says modestly.

At the time they were merely students […] passionate about journalism and concerned with its future. Now they have over 6,000 users

The idea for Compass News came as a response to the challenges that journalism currently faces. One is financial: with the fall of print media, publications have been forced to find other ways of producing revenue, and, as Matilde explains to me, ads are far from reliable. “They’re an awful experience for the reader and ad blocks are just a finger tip away.”

“We think the solution is a subscription model”, argues Matilde. “However, the subscription models currently available are too expensive for the general public, especially young people”. It was with this in mind that her and her partners came up with the idea of a bundle subscription that is affordable for students and gives access to a whole range of publications.

Image: Matilde Giglio

Another problem with news today is the echo chamber fostered by social media. Most young people now get their news from Facebook. Matilde explains to me how Facebook is designed to maximise positive engagement, meaning it’ll always show you stuff you’re likely to ‘like’. The result: you will only have your own opinions reflected back at you.

As Matilde’s co-founder Mayank recounted in a talk at Warwick back in March, the tipping point for him were the 2015 general elections. Mayank was certain that Miliband would win, so swamped had he been by articles and opinions that told him what he wanted to hear. How could he imagine that many thought differently? Compass attempts to combat this echo chamber through its ‘Perspectives’ feature, which gives readers a selection of articles demonstrating a range of different opinions on the same topic.

Facebook is designed to maximise positive engagement, meaning it’ll always show you stuff you’re likely to ‘like’.

Matilde acknowledges that finding this range can often prove difficult: “The publishers that we have on board are very much liberal… we do include work from authors who perhaps are not entirely line with the general editorial voice—for example certain authors of the Guardian who aren’t as left-wing. There was a long discussion here in the office on if we wanted to include Breitbart—they sometimes produce interesting political analysis.”

I ask Matilde whether Compass addressees one of the other major problems with media today: the growing phenomenon of fake news. She nods enthusiastically. “I think that the filter bubble and the fake news problems are very much related. One of the reasons for fake news and people’s belief in them is because of the polarised opinions that everyone is already accustomed to seeing on their newsfeed. We become blinded to the other side of the argument and easily swayed by opinions that tell us what we want to hear.”

Matilde and co-founder Mayank. Image: Compass News

“The first thing we do to tackle fake news is give access to trustworthy sources. Unlike Facebook, our content is curated, only a few, selected publishers are available.” Indeed, some of the publishers Compass currently works with are the Financial Times, The Economist, The New York Times, and The Washington Post. “Secondly, we believe that if we instil in young people the habit of reading and seeking great journalism from an early age, they will become more media literate and less likely to fall for a piece of fake news”

But how did two young and inexperienced students manage to secure links with such prestigious publications? “It was actually the most terrifying thing in this entire venture—because publishers are old organisations and they aren’t really keen to experiment. It took us more than one year to get these agreements in place. What convinced them was the fact that we were aiming at a demographic that is not paying for their content as it is.”

If we instil in young people the habit of seeking great journalism from an early age, they will be less likely to fall for a piece of fake news.

Matilde’s passion for engaging students in quality journalism is obvious. “We think that if you have access to the best information, you will make better choices. Or at least more informed choices. We want to give young people the tools to be better informed.”

I mention how among the student population, misinformation is frequently seen as a fault belonging to older generations—generations that we seem to view as blinded by out-dated values and prejudices. According to this mentality, would it not be of even greater importance to give these demographics “the tools to be better informed”?

“Interesting question. Obviously misinformation is not confined to one generation. But I do believe the older demographic already has the tools to be informed. They have more income, and thus are more likely to afford that information.”

The question of accessibility didn’t seem to cross of the mind of the investors with whom Matilde and her partners initially met. Instead, many seemed to believe that the reason young people didn’t subscribe to news outlets was because they simply weren’t interested in current affairs. “We went through 18 meetings where people said you guys are good, the idea is good. However, we don’t think young people are that interested in news.” Even through the faulty sound quality of a Skype call, I could hear the frustration in Matilde’s voice. “Many people think that young people only ever read Buzzfeed or watch videos on Snapchat.”

Matilde and the rest of the Compass team. Image: Matilde Giglio

Not only does Matilde disagree with such pessimistic assumptions, she is also very much opposed to the idea that journalism as a whole is in its death throes. “To be honest, I think this is great moment for journalism.”

Matilde is confident that Compass offers a model for the future of the industry. “If you think of other content providers, with regards to music, videos, films…in the end, what works really well is a bundle subscription that gives you the best content and that allows you to get much more than a single subscription would.”

To be honest, I think this is a great moment for journalism

While Matilde has big hopes for Compass, she does not fail to acknowledge the difficulties of setting up a company. “Everyone thinks that with doing a start-up you lead a super cool, interesting life. Yet the reality is that you simply don’t have time for anything else: you end up friendless, single, and at least two kilograms fatter”, she says, laughing. For Matilde, what redeems this is her passion for Compass and the great relationship she has with the rest of the team. “I am best friends with everyone else in the team. Literally, all of us. There’s an incredible atmosphere in the office.”

Matilde reiterates the importance of passion later, when offering tips for aspiring entrepreneurs. “The most important thing is to do something you really, really, care about. You will be working at this 24/7– even on a personal level, it’s not easy. If you are doing something you care about and think is important not just for you but for others you’re less likely to quit.”

As we prepare to end the call, I ask Matilde how she manages to switch off. “I’m working on it”, she admits with a smile.

Comments