Japan’s Negative Interest Rates: an analysis of the Yen depreciation

BOJ’s monetary easing’s impact on exchange rate and international trade

The latest GDP data (2016 3rd quarter) shows Japanese export contributed 15.84% of its GDP, underlining the importance of gaining trade surplus for economic growth. Although by 2016 it was clear the future of this growth was in jeopardy, Japan’s monetary stimulus was a typical example of the J-curve. The blessings of the Yen depreciation were eventually short-lived.

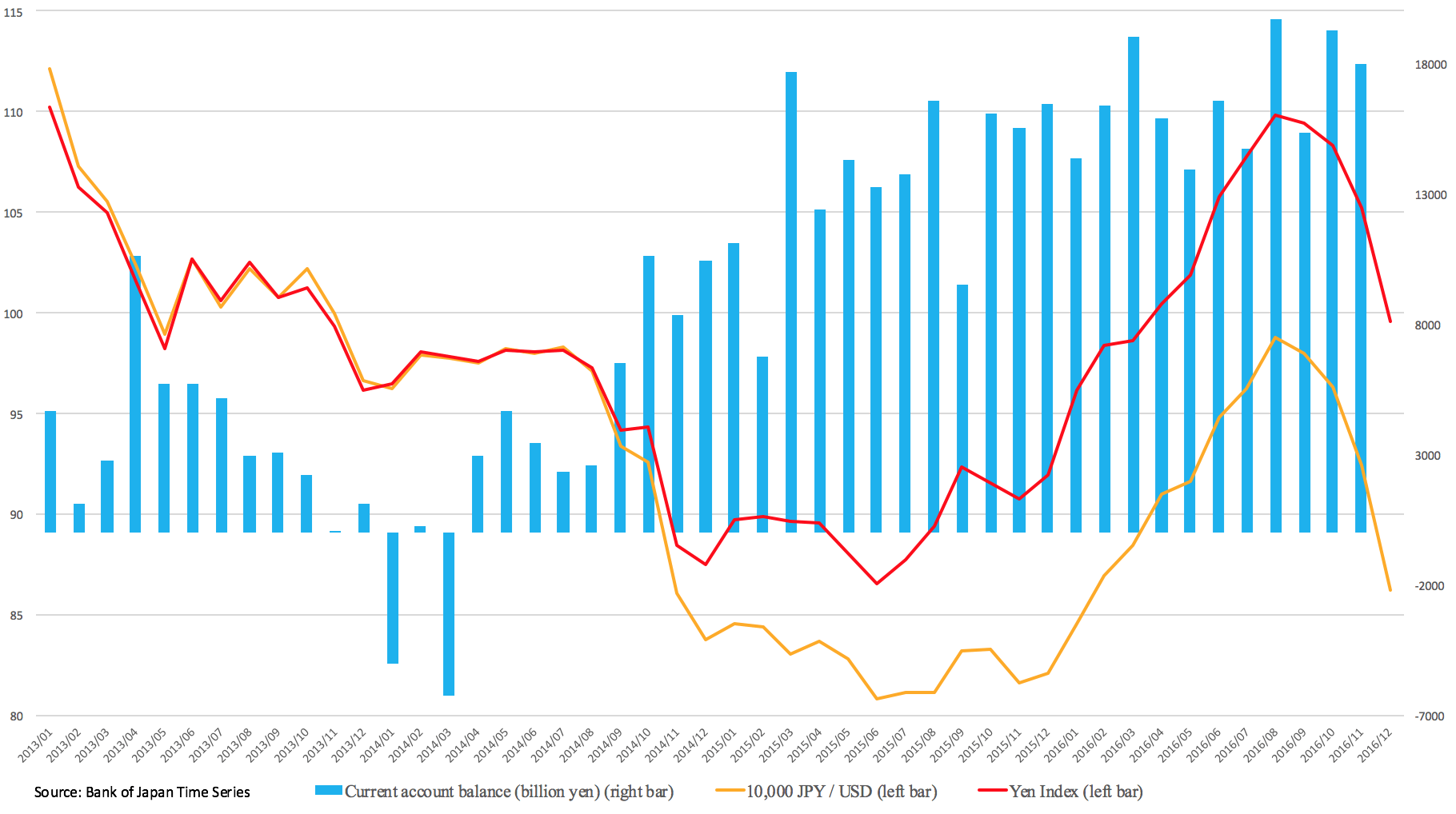

In 2013, Bank of Japan (BOJ) firstly signalled, then started to enlarge its monetary stimulus programme by buying more JGB and thus supplying more fresh cash to the economy, attempting to drive up the inflation and push down Yen’s exchange rate. Yen dropped, as expected, continuously throughout that year. In October 2014, BOJ further pushed Yen by an enlargement of JGB purchasing, making Yen touch a decade low.

Image: Graph by Parley Yang

A Closer Look at Trade

The immediate gain in trade surplus was small as short-term price stickiness prevented exports from obtaining immediate price competitiveness. Starting from 2014, exports fully enjoyed the price competitiveness contributed by cheap Yen. Imports lost the Japanese market as they were relatively expensive, and the desired result of economic growth fueled by a huge raise in net export, was achieved.

Starting from 2014, exports fully enjoyed the price competitiveness contributed by cheap Yen

The momentum of trade surplus continued throughout 2015, yet, the long-term effect of J-Curve suggest that, the rise in net export would increase the demand for Yen and drive up its value. This would eventually dampen price competitiveness of export, and pull back trade surplus. To avoid this, BOJ announced the negative interest rate policy in January 2016, and tried to avoid Yen’s appreciation from its stable low level.

A role for uncertainty

BOJ’s negative interest rate shocked the market, and Yen weakened for a few days. However, the Yen’s trend remained bullish, in part due to global uncertainties. Events such as the Chinese economic downturn inherited from 2015, Brexit and Trump’s victory, motivated Japanese investors to avoid oversea investments. Instead, they purchased back Yen. This caused an extraordinary appreciation of Yen, disregarding the low, or even negative interest rate in Japan. Further monetary stimulus by BOJ in July and September only momentarily paused Yen’s appreciation, and Yen rallied back to its 2013 level against major currencies by September 2016. This trend of appreciation has weekend the momentum of gaining trade surplus, and underlined the possibility of downturn in export. By the end of the year, Yen started to depreciate quickly, because of the Fed’s signal on a more frequent interest rate hike, whilst BOJ keep executing its massive JGB purchase.

the Chinese economic downturn inherited from 2015, Brexit and Trump’s victory, motivated Japanese investors to avoid oversea investments

It seems clear that if Yen continued depreciating throughout 2017, trade surplus should have further gains, thus assisting further economic growth and helping to reach inflationary target.

Image: Graph by Parley Yang

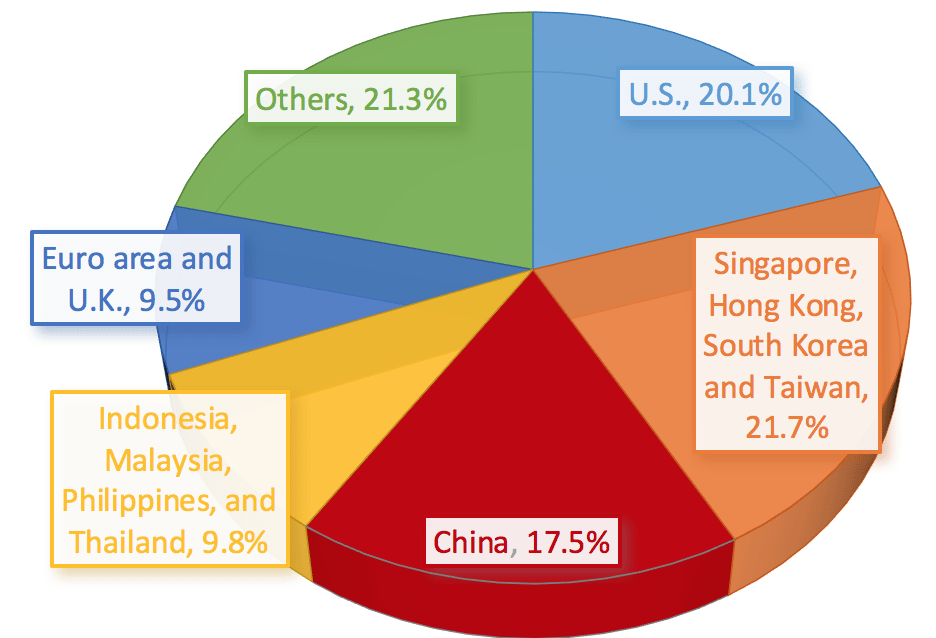

Nonetheless, the situation of Japan’s major trading partners also weighs in on a further trade surplus. With China’s GDP growth being likely to recreate a thirty-year-low spot at 6% by 2018, and the uncertainty surrounding Trump’s plans for trade barriers or negotiations, BOJ monetary policy may not be enough.

Mega banks being affected by the negative interest rate policy

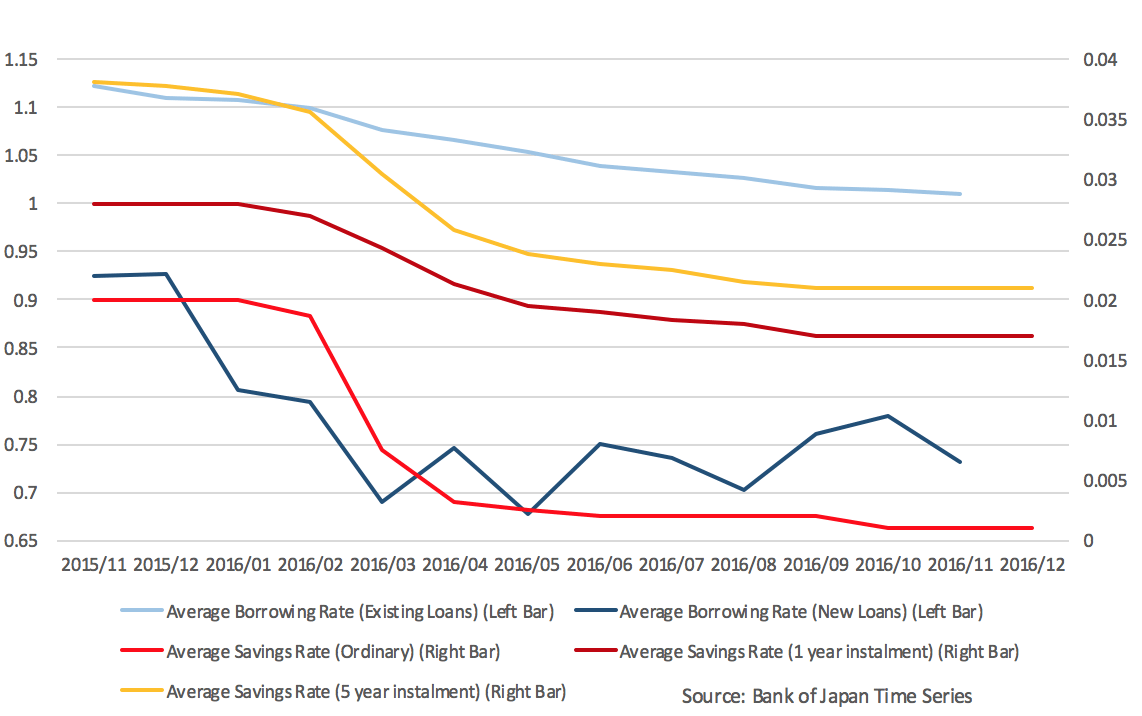

Since the crisis, banks are becoming reluctant to lend and have obtained higher-than-usual reserves. The negative interest rate policy not only lowered market interest rates, but also encouraged banks to rebalance their portfolios, directing investment towards riskier assets and perhaps more lending.

Image: Graph by Parley Yang

The largest bank in Japan, Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group (MUFG) experienced significant changes in its operating environment. A few days after the announcement of negative interest rate, on 8 February 2016, MUFG decreased its interest rates on savings accounts. Two weeks later, it promoted property loans, at a 10 Year fixed mortgage rate of 0.8%-3.15%. The negative interest rate is putting downward pressure on the bank’s interest income, causing uncertainty in engaging new investments in the retail and corporate sectors of MUFG’s operations.

The return of investment in securities had also shrunk, due to the decrease in JGB yield, which lowered incentives for further investment. Banks are thus forced to compensate losses by raising fees and increasing interests on loans. For example, MUFG enhanced risk-return management, by approaching higher marginal gains and a limited range of eligible borrowers.

Banks are thus forced to compensate losses by raising fees and increasing interests on loans

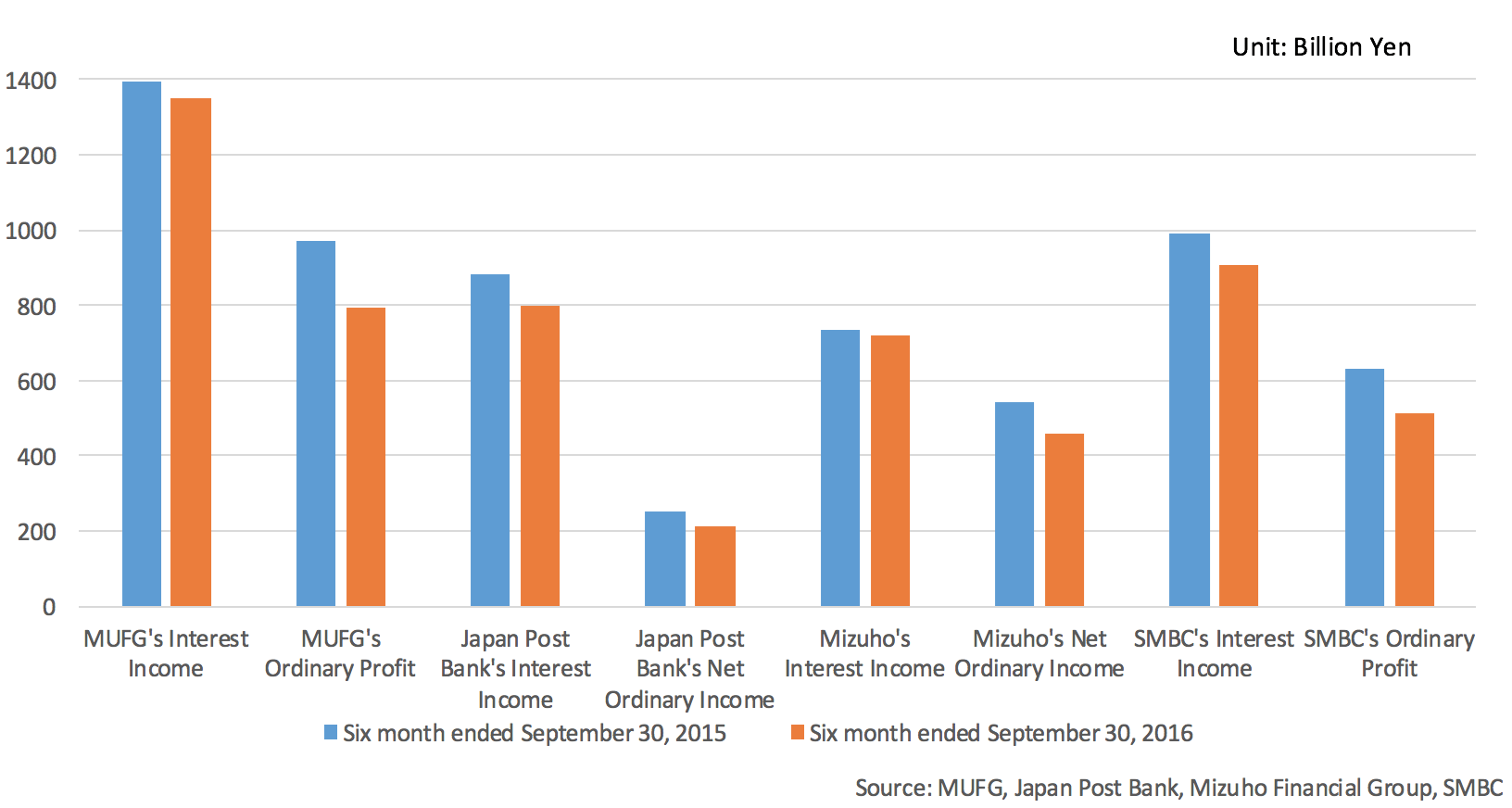

No Japanese major banks avoided a decrease in the ordinary profits and interest income. Still, all of them remain confident in accommodating the new fashion of BOJ’s policy environment.

This piece was adapted from Parley Yang’s research on the Bank of Japan.

Parley is a Mathematics and Economics student at Warwick. Parley carried out research investigating the effects of the Bank of Japan’s monetary policy between 2013 and 2016. His research was composed from a plethora of sources: statements by the BOJ and press conference’s records, data from Japan Cabinet Office or BOJ Time Series, interviews with professors and lecturers here at Warwick, emails with other scholars, and a meeting with Japanese students who study economics-related majors.

Comments