Carrie Fisher: More Than Just a Princess

At the end of a year that brought an onslaught of celebrity deaths, it was Carrie Fisher’s passing on 27th December that dealt me the heaviest blow. Known to thousands as Star Wars’ Princess Leia, Fisher’s hugely influential role in the franchise has dominated popular culture for the past forty years; defying previous gender stereotypes as a princess who could lead a rebellion, fight her own battles, and not be reduced to a love interest. However, whilst Leia served as a feminist icon to many young girls over the past four decades, to reduce tributes to Fisher to her character alone would be a disservice to her monumental impact as a writer, script doctor, and refreshingly outspoken mental health activist.

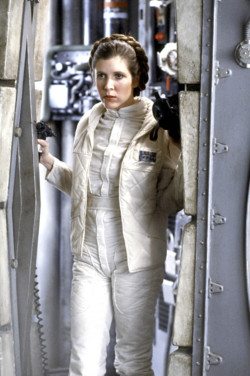

In a world of Disney princesses, Leia subverted stereotypes, rescuing the male characters as often as she is rescued herself.

Undeniably, the influence of Star Wars on popular culture remains unparalleled to this day. Like many children from 1977 onwards, my mother and uncle grew up with Star Wars, and therefore so did my brother and I. We had countless toy lightsaber battles, queued excitedly to ride Star Tours in Disneyland, and bought enough merchandise to make Walt Disney rub his hands with glee from the grave. The overall franchise played a prominent part in my childhood. It was always Fisher’s strong-willed Princess, however, who influenced me the most.

Even with the prequels featuring other female characters such as Padme Amidala, it was Princess Leia I pretended to be as a small child, befriending the toy Ewoks my mother had bought herself when Return of the Jedi came out in 1983. In a world of Disney princesses, Leia subverted stereotypes, rescuing the male characters as often as she is rescued herself.

a badass princess who, when forced to wear an embarrassing costume by a giant space slug, managed to free herself by strangling said space slug to death.

Though Luke Skywalker and Han Solo come to her rescue in A New Hope, Leia is the one who has to help them escape. In Return of the Jedi, Leia leads the mission to save the imprisoned Han from Jabba the Hutt. Of course, the infamous gold bikini Fisher wore as Jabba’s slave remains a subject of controversy with regards to Leia’s role as a feminist icon. While the bikini is rightly seen as degrading and more than a little sexist today, all I saw as a child was a badass princess who, when forced to wear an embarrassing costume by a giant space slug, managed to free herself by strangling said space slug to death.

The character’s return in JJ Abrams’ The Force Awakens saw her title changed from “Princess” to “Ge neral,” in a clear attempt to toughen her, militarise her, and distance her from the typically feminine connotations of the ‘princess’ trope. Nevertheless, something I admired about Leia’s role in the original trilogy was the fact that she could be both. She could be a princess, occasionally wearing pretty dresses and elaborate hairstyles and having a love interest; and she could kick ass with a blaster, lead a rebellion, fight her way out of trouble and take charge of hundreds of people. She wasn’t a strong character just because she could fight “like a man;” she was a skilled political leader, as outspoken and intelligent as Carrie Fisher herself.

neral,” in a clear attempt to toughen her, militarise her, and distance her from the typically feminine connotations of the ‘princess’ trope. Nevertheless, something I admired about Leia’s role in the original trilogy was the fact that she could be both. She could be a princess, occasionally wearing pretty dresses and elaborate hairstyles and having a love interest; and she could kick ass with a blaster, lead a rebellion, fight her way out of trouble and take charge of hundreds of people. She wasn’t a strong character just because she could fight “like a man;” she was a skilled political leader, as outspoken and intelligent as Carrie Fisher herself.

The most importance influence she had on me, however, was the way in which she fought to normalise the discussion of mental illness

As I grew older, I began to admire Fisher for much more than the role which propelled her to stardom. As a writer, she published seven books, and was a ‘script doctor,’ editing and improving scripts for films such as Sister Act, Hook and The Wedding Singer. The most importance influence she had on me, however, was the way in which she fought to normalise the discussion of mental illness, and addressed the double standards of the film industry with an acerbic wit.

In interviews, books, and her one-woman play Wishful Drinking, Fisher talked frankly and at length about her struggles with addiction and bipolar disorder, never sugar-coating her experiences or seeking sympathy. She would repeat in interviews the phrase, “if my life wasn’t funny then it would just be true, and that is unacceptable.” Her raw and honest discussion was always tinged with this self-deprecating humour; as someone who has always stubbornly refused to talk about my own mental health, I was in awe of her paving the way for such open discussion.

[Fisher] had to fend off numerous criticisms of her ageing “badly” for the 2015 sequel, something her male co-stars did not face.

With an honesty rarely present in Hollywood, Fisher called out the film industry’s double standards as often as she could. She frequently referred to her paranoia about having to lose weight from the age of nineteen for Star Wars, and had to fend off numerous criticisms of her ageing “badly” for the 2015 sequel, something her male co-stars did not face. Never failing to find humour in the situations she ridiculed, she disclosed George Lucas’ reasoning for not allowing her to wear “underwear in space,” that it would apparently expand and suffocate her character.

It is only fitting that this tribute should end in her response to this claim, that encapsulates the sparkling wit and cynicism of a cultural icon who will be sorely missed – “no matter how I go, I want it reported that I drowned in moonlight, strangled by my own bra.”

Comments