Are print books really on the decline among children?

Children prefer reading print versions of books, rather than digital versions, according to a recent UK-wide survey The Digital Reading Habits of Children (2016) by charity organisation The BookTrust.

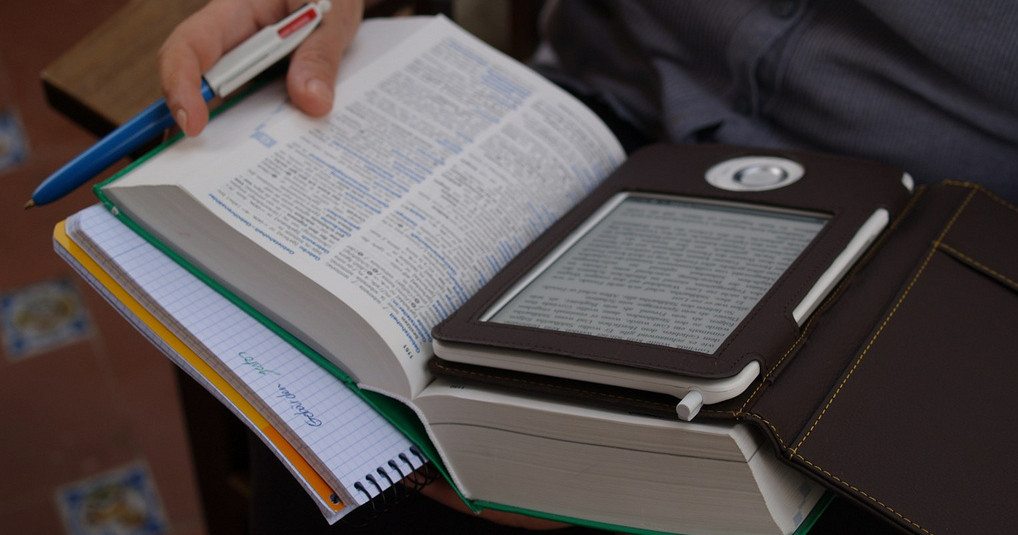

With the ever-increasing presence of internet technology, the widespread adoption of mobile devices and the digitisation of, it seems, any media product that can be digitised, there has been much speculation about the decline of the printed form. In his recent book ‘The Shallows’, Nicholas Carr laments society’s lack of interest in reading printed works, describing books as being in their “cultural twilight”, whilst there are no prizes for guessing the key message of Jeff Gomez’s book ‘Print is Dead’.

Children prefer reading print versions of books, rather than digital versions

With such doom and gloom messages for print publishing industries and endless rhetoric about how ‘the youth of today’ are addicted to the internet, slaves to their mobile devices and incapable of concentrating on anything beyond a 6 second video clip of a cat being outsmarted by a dripping tap, the results of the survey are perhaps surprising.

Of the 1,500 parents of 0-8 year-old children surveyed, 76% stated that their children preferred reading print versions of books, with only 15% reporting a preference for eBooks. The most commonly reported reasons for this preference were primarily experiential, such as enjoying turning the pages, ownership of a physical item and the experience of choosing a book from a library. Even in households where digital technology adoption was high, reported eBook consumption was low and print formats were still the preferred format for reading.

There is endless rhetoric about how ‘the youth of today’ are addicted to the internet, slaves to their mobile devices and incapable of concentrating on anything beyond a 6 second video clip of a cat being outsmarted by a dripping tap

However Diana Gerald, BookTrust Chief Executive, warns that discouraging use of digital books may carry risks, stating that “children will read online sooner or later” and therefore it is better that they are introduced to the medium whilst guided and accompanied rather than being “left to explore alone”. Gerald also stresses that digital books need not have a negative impact on a child’s reading experience, but can be used in “partnership with print books to enhance and encourage children’s reading for pleasure and can encourage further reading”.

It seems though that this advice may fall on deaf ears, as the majority of parents expressed concerns about perceived threats from eBooks, with only 8% expressing no concern at all. 45% expressed a concern that eBooks would increase their child’s screen time, with associated concerns around eye health and general wellbeing.

The majority of parents expressed concerns about perceived threats from eBooks

35% were concerned that their children would lose interest in the printed format altogether, indicating a desire to protect the printed book as a cultural product. Other concerns included the child’s exposure to inappropriate content (31%), excessive advertising (27%) and long-term effects on the child’s attention span and concentration (26%).

With these results, it seems that Carr and Gomez may be a little premature in sounding the death knell for the printed book.

Comments