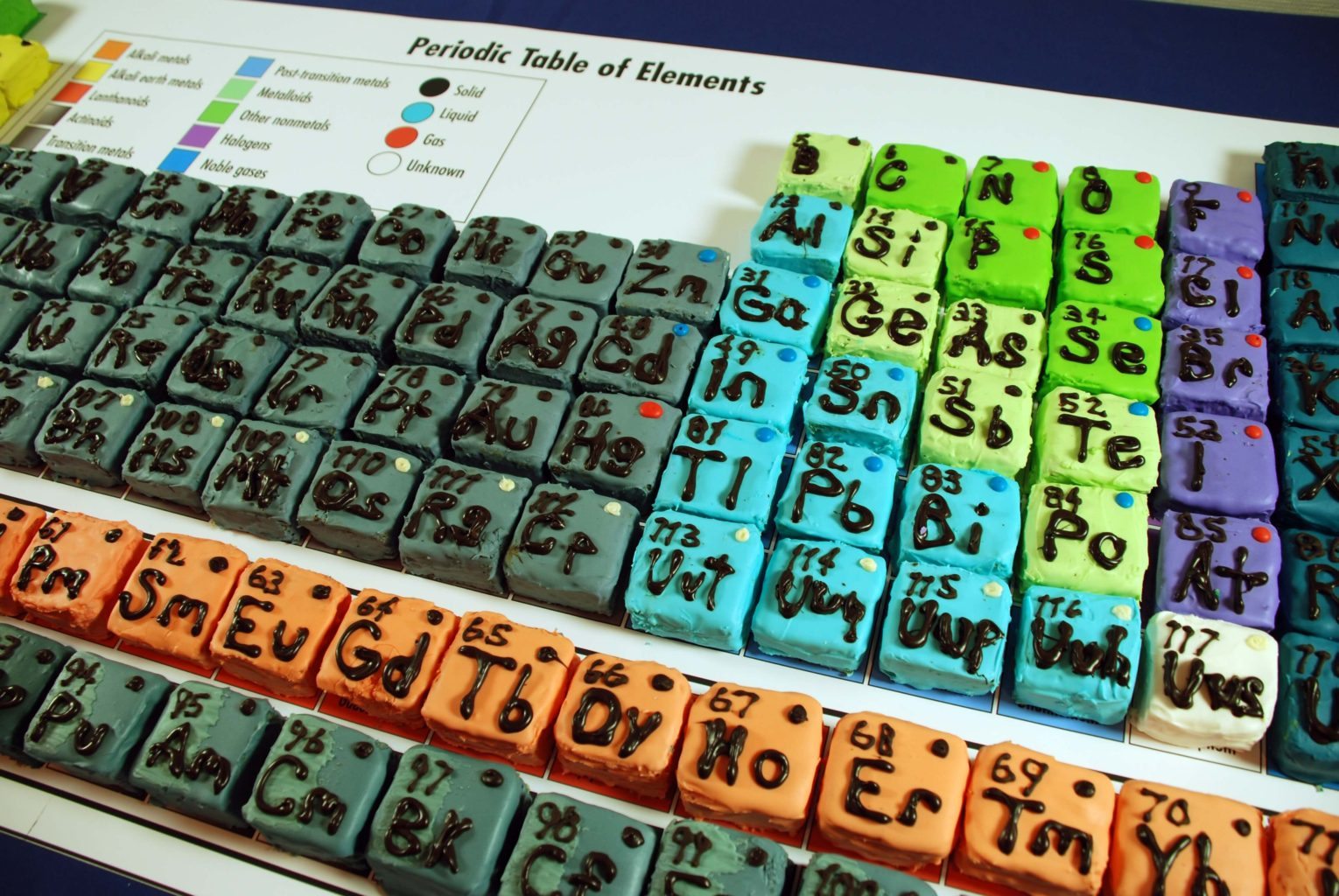

New year, new table

One of the iconic images of science, the periodic table, has changed for ever; as of the start of the year, all previous reproductions of the table became outdated with the confirmation of four new elements.

The addition of the four – elements 113, 115, 117 and 118 – completes the seventh row and comes after years of work from institutions in the US, Russia and Japan. The process of confirmation of such discoveries is a long one, requiring approval from both the Institution of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and the physics counterpart IUPAP.

The new elements fall into the category dubbed ‘superheavy atoms’ and are also entirely synthetic, as they are too unstable to exist naturally on Earth. The method of their creation falls into the realms of physics (sorry, chemists). Heavy elements are bombarded with lighter ones in hopes the two will fuse to create atoms with new atomic numbers. The Japanese team behind element 113, for example, showered a bismuth-209 target with zinc-70.

The discovery of element 113 (formerly ununtrium) is particularly important as it is the first to be claimed by an East Asian team, led by Kosuke Morita at the RIKEN Nishina Center for Accelerator-based Science. As the former president of the institution said, “To scientists, this is of greater value than an Olympic gold medal”. Work on the element had been going on as far back as 2003, but it more convincing evidence that lead to the confirmation came in 2012. The instability of a decay product was the main source for uncertainty regarding its existence.

The elements of the atomic numbers 115 and 117 are the result of the joint efforts of three institutions; two in the US (Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and Oak Ridge National Laboratory) and one in Russia (the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research). Notably the Lawrence Livermore group is headed by a female scientist, Dawn Shaughnessy.

To scientists, this is of greater value than an Olympic gold medal

This also means the dry place-holder names of ununtrium, ununpentium, ununseptium and ununoctium can be done away with. The teams have full naming and symbol rights, within certain IUPAC guidelines: the symbol must be completely unique and the name drawn from mythology, a mineral, a scientist, a place/ country or a property. Nevertheless, the public have put forward their own suggestions – a petition to honour Terry Pratchett by naming element 117 ‘Octarine’ has over 47,000 signatures. Meanwhile Lisa Seller of UCL wants a name to commemorate overlooked female chemist Lisa Meitner who, she says, was the first to spot nuclear fission.

Although it will be a while yet before the elements are named and so properly incorporated into the table, scientists including Morita’s team are already looking to create the next superheavy element, number 119. This would create a new row, as the table can now be considered ‘complete’ as its gaps have been filled. Stability issues mean this is still far off, although some place hope in the proposed ‘island of stability’: elements beyond uranium that show unusual stability. Those belonging to the island could potentially be useful even in chemical reactions, unlike the four new elements. Nonetheless, their confirmation is yet another feat of science and ‘finishes’ what was started almost 200 years ago.

Comments (1)

mbdu7evqqwaqpkj1u37s