Struggling grid cells linked to Alzheimer’s in young adults

New research from the German Centre for Neurodegenerative Diseases has suggested that the genetic element to Alzheimer’s might take affect much earlier in life than previously thought. Alzheimer’s was once thought of as an old person’s disease which picked off the kind and the brilliant, the healthy and the unhealthy indiscriminately.

But this choice of words is behind the times; it is becoming clear that Alzheimer’s does discriminate, and the genes involved are now being tirelessly investigated.

If you knew that your future held an Alzheimer’s diagnosis, would you want to know? The answer, which I imagine would be a cautious “no” for most people, may have to change as a result of the latest research coming out of the German Centre for Neurodegenerative Diseases in Bonn; it has been suggested that the damage to the brain may be caused decades before symptoms first appear.

This could mean that young people will have to start thinking about “old age” diseases whilst still in their primes.

The study, published in the latest edition of Science, saw two groups of people aged 18 to 30, those with and without a high genetic risk of developing Alzheimer’s later in life, attempting to navigate their way around a virtual maze. The two major symptoms of Alzheimer’s are memory loss and spatial disorientation, and in this experiment the researchers, led by Lukas Kunz, attempted to find out whether or not there was a significant difference between the performances of the two groups.

And there was: those at a high-risk were markedly worse at navigating the maze.

Navigational skills derive from the entorhinal cortex, a kind of hub that is also important in memory formation and consolidation. It makes sense, then, that this area of the brain appears to be the first to fall victim to Alzheimer’s. The entorhinal cortex contains grid cells that are specifically involved in spatial navigation.

The brain can construct an internal map of our surroundings, splitting our environment up into equilateral triangles; grid cells fire whenever we move into a new triangle of this quite remarkable mental tiling system.

It has been suggested that deficiencies in the function of grid cells explain the spatial disorientation seen in patients of Alzheimer’s.

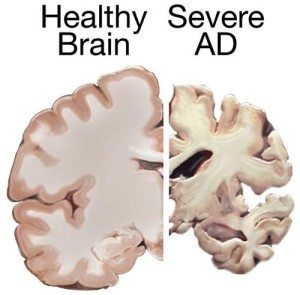

This latest finding, which appears to show that the damage to the brain can occur much earlier than previously believed, may also explain why it has been so difficult to find a cure, or even effective therapies, for the disease.

Our efforts so far may have been too little, far too late.

Comments