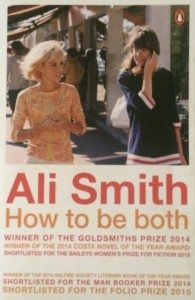

How to be both

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]li Smith’s How to Be Both has turned the heads of every dedicated bookworm out there. This is no surprise considering the fact it was shortlisted for the 2014 Man Booker Prize and won a variety of other awards, including the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction 2015 and the 2014 Goldsmiths Prize.

Smith’s book is all about duality. The form of the novel itself is unique and plays with the idea of interconnectedness. Split into two halves, it tells the story of artist Francesco del Cossa in the 1490s as well as that of a teenage girl called George who is discovering herself as she faces her mother’s death.

Smith’s book is all about duality. The form of the novel itself is unique and plays with the idea of interconnectedness. Split into two halves, it tells the story of artist Francesco del Cossa in the 1490s as well as that of a teenage girl called George who is discovering herself as she faces her mother’s death.

Half of the copies published tell George’s story first and the rest tell del Cossa’s first, creating an element of excitement when you begin reading. What’s more, you absolutely cannot assume that the order you read the stories in won’t impact your reading experience. It is a complete reinvention of the form of the novel itself, seeing as both stories are connected and play with the idea of time within novels. No matter what you read first the two stories click, but perhaps click differently depending on order. The story itself means something else, and we entertain different possibilities depending on which half we come across first.

The story itself means something else, and we entertain different possibilities depending on which half we come across first.

Having ended up with del Cossa’s story first, I feel like I plucked the slightly shorter straw. It was only after starting George’s narrative that I felt hooked, and what I had already read began to make more sense. Although del Cossa’s point of view is beautifully and authentically written with a stream of consciousness feel to it and unconventional sentence structure almost like poetry, it is not easy to get into. There are moments of brilliance when del Cossa wonders exactly what an iPad is, as he interacts with George’s world, but it is after George’s narrative that I reread my first half. It was an easier read, and opened up so many more imaginative possibilities, such as seeing the entire portion of del Cossa’s narrative as a product of George’s imagination considering her school project on him.

Duality is also a major theme. Further transcending the boundaries of time, sexuality and gender is present in both halves if the novel. George is beginning to discover who she really is as she grows and it seems no mistake that she is called George, as well as the fact that del Cossa is born a girl but lives as a man. Genders are blurred in del Cossa’s paintings, which George also notes, and this is another way Smith effectively and subtly plays with duality and layers. It doesn’t boldly assert itself as an issue though, and so doesn’t become a cliche way of dealing with a sensitive topic. George’s mother’s conclusion that it doesn’t matter if the figures in the painting are male or female sums this up perfectly.

Duality is also a major theme. Further transcending the boundaries of time, sexuality and gender is present in both halves if the novel. George is beginning to discover who she really is as she grows and it seems no mistake that she is called George, as well as the fact that del Cossa is born a girl but lives as a man. Genders are blurred in del Cossa’s paintings, which George also notes, and this is another way Smith effectively and subtly plays with duality and layers. It doesn’t boldly assert itself as an issue though, and so doesn’t become a cliche way of dealing with a sensitive topic. George’s mother’s conclusion that it doesn’t matter if the figures in the painting are male or female sums this up perfectly.

Smith treads the line between being so clever that it is difficult to understand, and being… radical in order to reinvent a conventional novel

Smith treads the line between being so clever that it is difficult to understand, and being extraordinarily challenging and radical in order to reinvent a conventional novel and create a different type of reading experience. Definitely worthy of the accolades it has won, How to be Both can be referring to being both female or male (or neither). It can also be referring to being part of the 1490s or the present day considering the fluidity of time, or something else that hides underneath the many layers of the novel. It is, above all else, brilliantly clever, witty and original in both its form and substance.

Image credits: Header (commons.wikimedia.org), Image 1 (Karishma Jobanputra photography), Image 2 (commons.wikimedia.org)

Comments