Tête-à-tête: Do you support or condemn assisted dying?

[one_third]

Zoë Morall is FOR

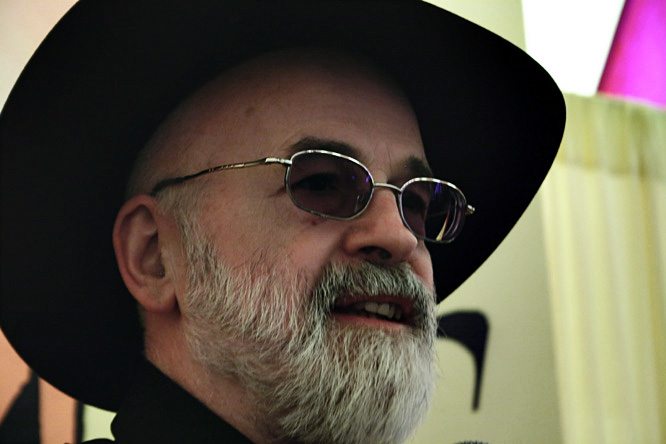

[dropcap]L[/dropcap]ast week, Terry Pratchett died. He became a prominent figure in support of euthanasia in this country. He made a very moving documentary called ‘Choosing to Die’ (which I recommend that everyone watch) in which he spoke to several people with terminal illness, some of whom travelled to Switzerland where they were assisted to die.

I have read many articles, for and against this issue, but nothing was more enlightening than this film. One spouse of a terminally sick man said that she would never allow her pet to endure a painful and degenerative disease, but would put it down as an act of humanity and kindness. I think that this is a useful analogy to make. We value human life above the life of an animal; therefore the thought of putting a beloved dog out of suffering isn’t seen as similar to a human in position of pain. And while I am not trying to say that these two situations are the same, they are not, the principals are. There comes a time when it is kinder to let go and allow someone to be in peace.

If someone is living a life at a standard that they deem unacceptable, what right does any government or individual have to, in effect, force them to continue living? The religious argument is problematic because it leaves no room for human choice, and the feelings of an individual. In stating that all life is worth saving and prolonging, it deprives people of autonomy and control over their own life (one might draw parallels between this argument and religious arguments against abortion).

Furthermore, the world is not entirely religious. Atheism is alive and kicking, and I do not see why religious doctrine should be able to define law. I believe that this country should cater to all its citizens, represent the views of both religious and non-religious people, and offer choice. If one does not agree with euthanasia, then surely one does not have to participate. But to deprive somebody else seems wrong to me.

If we were to follow the Swiss model, no doctor or medical professional would be required to administer a drug. In Switzerland, it is the individual who drinks the fatal draught, and it is done entirely alone. This requires a person to be in a state of mind to make this decision (and a doctor also meets with each individual to ensure that they are sound of mind).

I think this method (shown in Pratchett’s documentary) would help protect against many of the fears expressed by people who think that it is unreasonable to ask a doctor to administer a fatal injection or to cause unwanted deaths because of the selfish choice of family members.

Terry Pratchett very poignantly asked, “who owns your life?” In my opinion, the answer is clear: you do, and no one should be able to force you to do anything, and that includes staying alive against your will.

We must ask ourselves what we would do, if a loved one or ourselves were in a position of suffering. It is very easy to be selfish and not want to let go of people. Some might find euthanasia perverse, or unnatural, but death is always difficult whenever it comes. But out of all the ways one could die, in an accident or suddenly of health issues, is there not something comforting in knowing when and how one will die? Is it not reassuring to know you can leave on your own terms, in a painless way, particularly if you are sick? We cannot conquer death, but we could choose when we cease to exist, and that is quite a privilege.

Assisting someone to die peacefully, painlessly, and with dignity seems like one of the kindest things we can offer. I personally do not want to end my life in pain, humiliation, or distress, and I believe that euthanasia offers another option.

My beliefs are not so rigid that I cannot understand the arguments against euthanasia, and even at times, sympathise and agree with them. However, particularly after watching Pratchett’s documentary, and seeing real people made to feel degraded and weak by their illness, and rationally making a choice to die, I think it is impossible for me to be against it. If we legalise euthanasia, we are taking a step into difficult territory, but I think it is a step that we should take. It will be a real challenge to make regulations, but I believe it is one that we should accept.

What is YOUR opinion on assisted dying?

Tweet to @Boarcomment or like our Facebook page: Boar Comment to comment on the issue

[/one_third] [one_third_last]

Andrew Armstrong is AGAINST

[dropcap]F[/dropcap]ounded in 1998, Dignitas is the preeminent centre for Assisted Dying in Europe, and was visited in 2012 by the author Terry Pratchett, one of its most vocal proponents in the UK. The way Dignitas operates, as described by Pratchett, has left me firmly opposed to assisted dying.

Assisted dying differs as an issue from other matters of life and death because it is not merely an issue of bodily integrity or self-determination. Since people have very little business telling you what to do with your own body, suicide and abortion should remain legal, and like abortion, assisted dying is a matter of bodily integrity and choice. However, the chances of a decision being swayed by other parties are in my opinion much greater with assisted dying than with abortion. This is because a relationship with a family member considering assisted dying is much more established and long lasting than with an unborn child.

One of the main attractions of assisted dying is that the process is done in relative comfort, in the company of your family, at a time of your choosing. This is however much like current hospices, or palliative care, with the difference being that hospices and hospitals don’t actually try to kill you. Presumably the attraction is also to save them the burden of caring for you during a long period of senescence. It is not unreasonable to assume that a sufferer could unfairly internalise a sense of guilt at this and at their condition, nor is it unlikely that they could be manipulated into this state by someone who has something to gain (or lose).

Furthermore, whilst the pain of a degenerative illness is shocking and overwhelming, it’s additionally worrying that Dignitas isn’t exclusively reserved for people suffering from these progressive or terminal conditions. In-house statistics do not make clear how many people there are suffering from depression, but what is clear, according to Pratchett, is that 21% of those who die there do not suffer from clinical ailments but instead have a “weariness of life”. Notwithstanding that 1 in 5 of the population of the UK will have a mental illness at some point, or that almost all will be expected and encouraged to recover fully, this diagnosis seems so meagre as to be highly discomfiting. Even more sinister is the fact that instead of offering a hand up, the clinic provides a final push. Would a decision be different, under more supportive circumstances?

Patients, in making a speculative decision, are forced therefore to deny the possibility of new treatment, or of a more gradual descent than was expected. This is unlikely but not unheard of: a famous example being the exceptional life of Professor Stephen Hawking.

Also, the patients at Dignitas are there with no sense that they have anything left to contribute. Rather than providing dignity, Dignitas perpetuates this myth. Moreover, a parliament which passes an Assisted Dying Bill is admitting that life truly isn’t worth living for some, which given how an individual’s circumstances and attitudes can change is highly contentious, even whilst being in debilitating pain. Parliament rubber-stamping a Bill of this type is sending the message that terminally ill people cannot improve their lives on any level and that people dying in this way is for the good of others, especially since the process is designed to include family members or other people.

It need not be the case that people are robbed of dignity because of the attitudes of others, or feel compelled to end it all in order to cease being a burden. Chronic pain is hideous and grinding, but also hidden and more prevalent than many realise. Since chronic sufferers are vulnerable, their quality of life depends on the support and perception of others enormously, and not enough is done collectively to promote awareness of the range of conditions that are prevalent, or the range of measures that could be put in place in support.

Assisted dying could easily often make a bad situation much worse, and it also legitimises what could be a choice made emotionally and prematurely, rather than rationally. Therefore, before we make assisted dying legitimate and accessible in the UK, let us understand more about the science behind progressive conditions, the types of palliative care that are available, and understand where and how sufferers can still fit into society.

Pratchett himself documented and raised awareness of Alzheimer’s incredibly effectively. His viewpoint is wrong, though. The best way to die is simply after having lived the best life you could, through situations that challenge you to value companionship and compassion, rather than through the sterile eugenics of a trip to Dignitas. I believe that Terry Pratchett’s lasting contribution to the debate is not his advocacy of Dignitas, but the rich life-affirming language and ingenuity of his novels. Life, in all its messy imperfect forms, is to be lived.

[/one_third_last]

Comments