Wakolda

Director: Lucía Puenzo

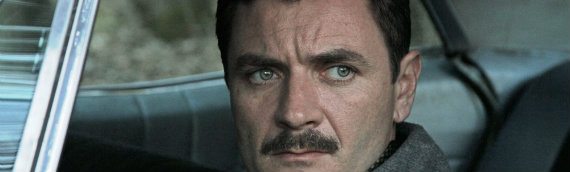

Cast: Àlex Brendemühl, Natalia Oreiro, Florencia Bado

Length: 93 min

Country: Argentina, Spain, Norway, France

For over thirty-five years, Dr Josef Mengele, Auschwitz’s ‘Angel of Death’, evaded capture, living in various parts of South America hidden in plain sight, and taking advantage of the open-door policy within Argentina for Nazi war criminals. Given his infamy and the gravity of his crimes, your first response to this information was probably a simple “how?”. Argentine writer-director Lucía Puenzo’s Wakolda (also known as The German Doctor) explores that very idea, blending fact and fiction to tell the story of the six months when Mengele’s whereabouts were unknown to the authorities. Wakolda proves Mengele achieved that ‘how’ with terrifying ease, and that’s one of the many things that makes this film so affecting. Adapted from her own eponymous novel, Wakolda is Puenzo’s third film, and draws upon themes surrounding coming of age and finding identity also present in her previous features, the critically-acclaimed XXY and The Fish Child (El niño pez). The material here is particularly sensitive, but is handled with the skill and restraint that has come to typify her work.

Set in 1960, against the picturesque backdrop of the Argentinian city of Bariloche (one of many places Mengele is believed to have lived during those ‘missing’ months and the real hiding place of Erich Priebke amongst others), which is home to a well-established community of German expatriates. Mengele (a powerful Àlex Brendemühl) lives alongside them under the assumed name of Helmut Gregor, passing himself off as a former doctor-turned-veterinarian who specialises in cattle genetics.The Mengele presented here isn’t looking over his shoulder at every turn, in fear of his life. Instead, he’s had to evolve, adapting to survive. Clever, calculated, and resourceful, he’s not just good at hiding; he excels at it, making himself indispensible to whoever he comes across. In this case, it’s a 12-year-old girl called Lilith (an impressive debut by Florencia Bado).

Lost in his unfamiliar surroundings, Mengele asks to follow behind the family car as they travel to re-open an old hotel formerly owned by Lilith’s grandparents. Though Enzo is suspicious he ultimately agrees, keen to move his brood and pregnant wife Eva (Natalia Oreiro) along before the weather closes in. Just as Enzo feared, rain comes lashing down and they’re forced to seek refuge en route, giving Mengele time bond with the curious Lilith and finds common ground German-speaking Eva, effortlessly switching between two languages. They’re clearly charmed. Once the storm passes, the family and Mengele travel on, and ultimately and go their separate ways, with Enzo directing him through next part of his journey. Brushed off as a strange an on-the-road encounter, the family continue to settle in at the hotel, but the story is just beginning. One morning, Mengele arrives at the gates, and when he’s invited inside, he asks to become the family’s very first guest. Though wary, the lure of Mengele’s six-month cash advance is enough to get them to agree.

Mengele’s fascination with Lilith is made clear from the start. She’s blonde-haired, blue-eyed. Quite perfect in all respects, save for one thing: she’s much smaller than she should be. Mengele’s keen eye spots this from afar while she’s at play with other local children, and introduces himself by rescuing a bedraggled, but obviously beloved doll from the street when it falls from the car the family are still loading.

Handmade by her dollmaker father Enzo is a curious looking little thing that Lilith prizes because she looks different from the rest of her father’s output. The worse for wear after years of play; Mengele fixes the toy, and wins Lilith’s trust. This doll is the Wakolda of the title, and this signals the start of many threads Puenzo weaves together across the course of the film concerning uniqueness, beauty, and the pursuit of perfection, all filtered through Lilith’s innocent eyes. It’s not a new perspective by any means, but it’s incredibly successful, as proven by The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas, The Book Thief and Sarah’s Key amongst others, and is just as effective, if not more so here.

Initially, despite the inescapable sense of foreboding that lingers in air – Brendemühl looks so like Mengele, his mere presence in any scene is enough to inspire fear – things for the family begin well in Bariloche. It’s the perfect place to play, and the perfect place to hide. Meanwhile, Mengele continues to grow closer to the family. First, he offers prenatal vitamins to Eva as the latter stages of her pregnancy become more difficult. Then he gives giving the financial backing Enzo so desperately desires to see his latest doll sketches brought to life. Pivotally, his offer to treat Lilith with the growth hormones he uses in cattle experiments is soundly refused.

However, once Lilith enrols at the local German-speaking school her mother used to attend, things take a turn. At first, she struggles to fit in because she understands, but can’t fluently speak any German, and then because she’s taunted by her peers for her height. Her only friend is a sweet-natured boy called Otto (Juan I. Martínez). She spends her playtimes in the company of Nora (Elena Roger, famous for her role on Broadway as Eva Peron) a local photographer and archivist working in the school (based on Nora Eldoc, the undercover Mossad agent who tracked Mengele’s movements). Increasingly isolated, Lilith makes a pact with her mother to begin treatment without Enzo’s knowledge. On the day he injects Lilith for the first time, Mengele examines Eva, discovering she’s pregnant with twins.

It’s to Puenzo’s credit that she doesn’t resort to cheap shocks or employ a heavy-handed approach that would render Mengele nothing more than an evil, cackling pantomime villain. The evil shown here has far-reaching roots. It has a face, and a name.

To say anything more would reveal far too much, but if your dread reading that last detail, you’re not alone. The crimes of Mengele are well-documented enough that all Puenzo has to do is nudge at the audience. The people of Bariloche are presented without judgment, but we are invited to do our own judging with the clues Puenzo places throughout. Childhood photographs and otherwise innocuous lines are given weight by their new context. “I like to weigh and measure things that interest me,” Mengele tells Lilith, with the same casual manner a birdwatcher or railway enthusiast might talk about their own hobbies. “You’ll find other twins,” offers a nurse colleague, drafted in from the clinic to help when Eva’s babies are born unexpectedly early during a heavy snowstorm. “Anyone would be honored,” trills Klaus Guillermo Pfening) a young teacher at Lilith’s school, when called upon to help Mengele throughout. It’s not the evil in this story – or indeed, the banality of it to quote Hannah Arendt – that’s the most difficult to process; it’s the sympathy and support for such evil that’s most unnerving.

A broader sense of Mengele’s deeds are given when Lilith narrates excerpts from Mengele’s infamous notebooks, the meticulous pages loom large on the screen, and it’s a relief when they stop turning. The implication of Mengele’s capabilities is enough, and Brendemühl’s performance combines the charm, menace and cool detachment Mengele is renowned for. Part of what makes Wakolda so unsettling is the fact we’re witness to the duality of Mengele’s character throughout. He can give with one hand, and take with the other, all in the name of science, progress, and doing ‘good.’ Charming and kind one moment, he’s fixing toys and chatting amiably, living up to his nickname of ‘Uncle Mengele’ who befriended and gave sweets to the children imprisoned at Auschwitz before experimenting on them. The next, he’s obsessively measuring drawing mysterious liquids from vials ready to inject, unaffected when Lilith starts to experience side effects from the hormones she’s receiving.

The tonal balance of the film might sound like it’s weighted too heavily on dark as opposed to light, but that’s not the case. Everything is balanced; finely tuned and delicate, much like the inner workings of Enzo’s dolls. Though the film’s neat – dare I say surgical? –precision might be off-putting to some, for me it only served to heighten the film’s tension. The parallels drawn between Mengele and Enzo are particularly striking. The similarity between the dollmaker’s plans and the doctor’s notes isn’t coincidental. They’re two men at opposite ends of the same spectrum: detail-oriented, astute, and driven. The difference that separates them is small, but the effect of that difference shows itself tenfold: Enzo has the boundless empathy where Mengele has none at all. With Mengele’s backing, Enzo’s dream of a doll modeled after his cherished daughter’s likeness, with replete moving limbs and a tiny mechanical beating heart loses its whimsical sweetness and becomes distinctly sinister. Enzo’s dolls are no longer unique or special, but they are perfect. The imagery of row upon row dolls in the factory is disturbing enough, but they look even worse when shown as decoration in the background of Mengele’s room at the hotel.

Placed in a position of privilege from the start, we can guess the real identity of Helmut well before he’s revealed as Mengele, and hold a much greater depth of understanding than young Lilith can grasp, so we’re constantly aware of the tick-tick-ticking clock, wondering when Mengele’s time will run out. It’s to Puenzo’s credit that she doesn’t resort to cheap shocks or employ a heavy-handed approach that would render Mengele nothing more than an evil, cackling pantomime villain. The evil shown here has far-reaching roots. It has a face, and a name. It could be living right next door to you without you knowing it. Most terrifying of all, you could know it’s name and it’s face, living with it ever day and choose to do nothing.

That’s how you hide in plain sight.

Image Source: Peccadillo Press

Comments