Memories: A mystery of the mind

Oscar Wilde called memory a diary that we all carry around in our head and Freud likened memory to a palimpsest: an old parchment on which the original text has been erased to make room for a new one.

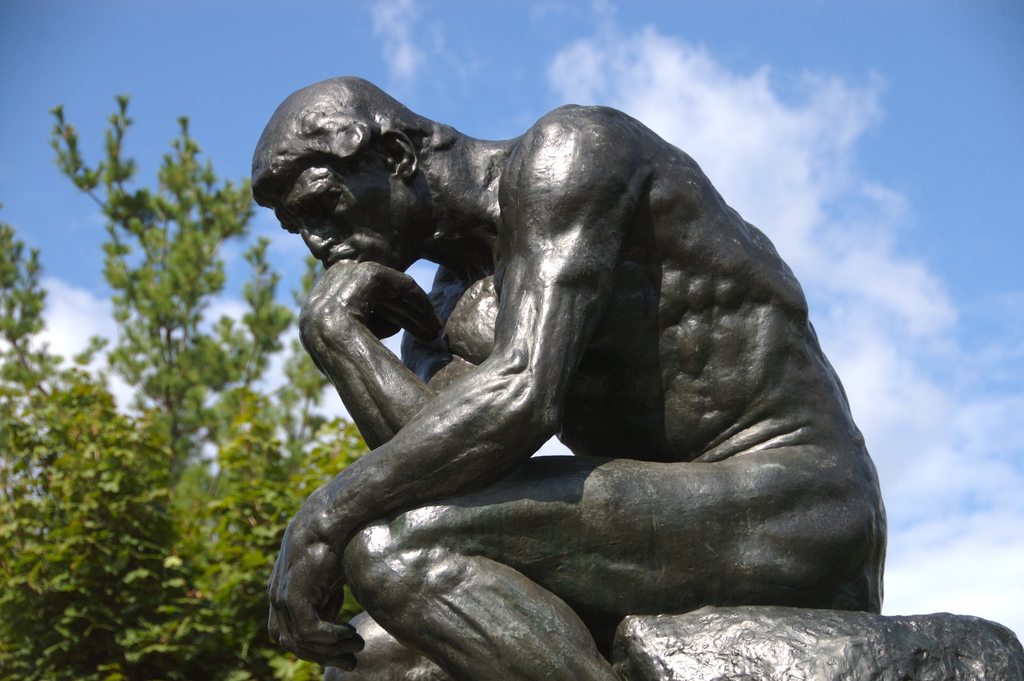

The brain is constantly rearranging its own architecture, and yet the “memory” still remains intact. If this sounds clunky, it is; memory defies easy description. The phrase “I remember” carries an enormous weight, and how this is achieved is perhaps the most intriguing question still unanswered in the life sciences.

Progress in the study of memory was slow up until the end of the 20th century. Until the development of neuroscience supplanted psychology, the study of memory was considered too difficult and mysterious; research funds were directed toward the elucidation of less demanding faculties. Though I am being simplistic, we now know that the site of long term memory storage is the hippocampus, a horse-shoe shaped component in the brain.

The senses of smell and taste are both directly connected to the hippocampus, whereas the remaining senses of sight, hearing and touch are first processed elsewhere, in the thalamus. This explains why smell and taste form longer lasting memories. For a long time, it was thought that the memories were fixed, permanent representations of reality that may simply become frayed or destroyed with age due to neural degeneration. Not so, recent studies suggest.

At the McGill University lab, researcher Karim Nader studied the memory of rats. He began by conditioning them to associate a loud noise with a subsequent electrical shock. He knew that the memory-making process requires the production of new proteins, and so injecting the rats with a chemical that inhibits protein production also prevented them from creating a memory of fear. But Nader took this one stage further, and injected the protein inhibitor after the loud noise had been played, while the rats were in the process of “remembrance”. Remarkably, the rats then lost the entire memory. One inhibition of remembrance was enough to wipe their entire memory of the pain that followed a loud noise.

In another recent experiment, people were asked to study the location of an object on a background picture (e.g. an underwater scene) and to try to place the location of this object in the correct place from memory, but on a different background scene. Most often, people chose the incorrect location. Next, participants were asked to identify where the object was on the original background from a choice of three: a random location, the original location, and the incorrect location on the different background. Participants always chose the incorrect location that they had previously picked as being the correct one.

In the words of the lead researcher, Donna Bridge, “This shows their original memory of the location has changed to reflect the location they recalled on the new background screen. Their memory has updated the information by inserting the new information into the old memory”.

These and other studies are making the tantalising suggestion that memories are not simply photographs, filed away until they are needed. Looked at in another light, it also suggests that not only can the past influence the present, but that the present can also mould the past. The very act of remembrance alters the memory. Without the original stimulus, the memory will become less and less about the literal truth and more and more about your present predicament (casting doubt on the concept of love at first sight). This leads to the unsettling idea that the memories we treasure the most are the ones that have changed the most. The best way to keep a memory intact is to never remember it.

Comments