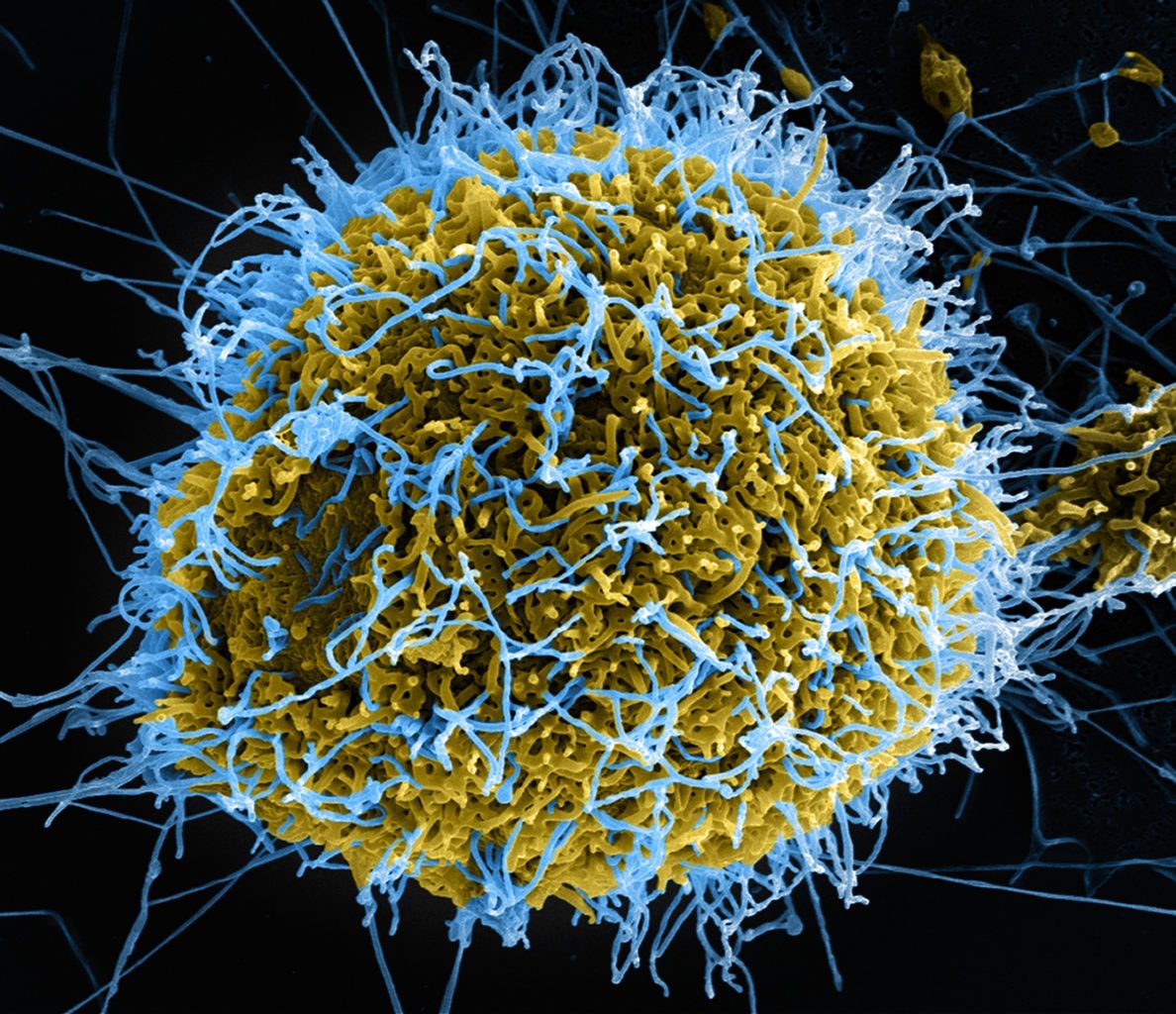

The Ebola outbreak: Can it happen here?

The outbreak of Ebola in West Africa is now the largest in history; Doctors without Borders claim that the situation is “out of control” and there are new fears that resources are running out to treat the vast number of sufferers. However, with a population that has lived through the rapid, international spread of viruses such as HIV and SARS, many are beginning to wonder whether the UK, too, will soon see its share of the deadly virus.

Scientists have suggested several reasons why the outbreak, which began December 2013, has been so explosive. The most popular theory points at a local distrust of hospitals as a primary cause of the spread of Ebola. Local people see patients be admitted into hospital for treatment and come out worse off or dead. Many have formed the assumption that by avoiding hospital, they will be able to avoid illness.

Further distrust of healthcare officials has arisen when officials tried to prevent traditional burial customs. These West African burials involve relatives of the deceased bathing, cleaning and dressing the victim’s body, finally issuing the body with a “love touch” or last kiss. As Ebola is still contagious when the body is dead, any of these practices could cause a further spread of the disease and officials are trying to prevent the traditions when burying the body.

Educating people about the disease has also proved difficult. With literacy rates in Sierra Leone around 35 percent, successfully informing the public on how to prevent the disease has proven tricky and is made much more problematic with the distrust of the healthcare system.

Currently, no vaccine has proven effective against Ebola. Present treatment involves replacing body salts, maintaining both oxygen levels and blood pressure and treating any secondary infections. Even with these treatments, fatality rates can still reach 90 percent, although currently they only reach 40% in Sierra Leone.

How would Ebola be treated in the UK? Derek Gatherer, a researcher at Lancaster University, suggests that a patient who displayed symptoms of Ebola and had recently travelled to any Ebola stricken country, would be swiftly isolated and provided with the appropriate treatment, by healthcare providers wearing appropriate protective clothing. This effectively limits the spread of the virus.

Additionally, the UK has a vast variety of media platforms to educate the population on other prevention methods. Many will remember the “Catch it, Bin it, Kill it” campaign that followed the Swine Flu pandemic in 2009. It is a slogan preached from TV and radio adverts, newspapers and billboards and educated people that helped bring an end to the outbreak. Therefore, it is the conclusion among many scientists that an outbreak like the one in West Africa just wouldn’t happen in the UK.

The future of the fight against the disease is looking hopeful. Currently, scientists are researching experimental treatments for Ebola, which have been successful on animals. One such treatment, ZMapp, has been administered to two U.S. patients in Liberia.

The costs for the treatments were arranged privately by Samaritans Purse, a private humanitarian organisation. However, the CDC does not think that this drug will be available to West Africans because it has not undergone the appropriate clinical trials yet. In addition, the resources to produce the drug on a large scale are not available to the manufacturers.

This certainly raises the question of why two Americans were granted the drug but not their African counterparts. Furthermore, if such an outbreak occurred in Western countries, would more resources have been spent finding treatment? It is called, after all, the drugs industry.

Comments