A conversation with historical novelist Karen Maitland

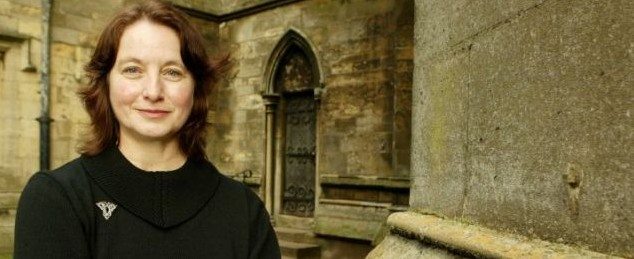

[dropcap]I[/dropcap] met Karen Maitland, the best-selling author of medieval thrillers, at The Collection Museum in Lincoln last month. We had spoken previously, about two years ago, when Maitland had just released an earlier novel: Falcons of Fire and Ice. After four years of working with The Young Journalist Academy, I’ve been lucky enough to interview a lot of very interesting people with a lot of very interesting things to say, but my conversation with Karen Maitland had always stayed with me, very clearly, in my mind.

I remembered her anecdotes of exploring hot springs in Iceland, of living in Nigeria during the civil war. I remembered asking about her degree in Psycholinguistics and feeling awestruck by the findings of her thesis – information now used by the police in criminal investigations. Most of all, however, I remembered how the audience had been almost completely silent for an hour, glasses of complimentary wine clasped unmoving and untouched in their hands as they listened, completely focused, upon the figure of Karen Maitland as she stood in the spotlight, talking about her book.

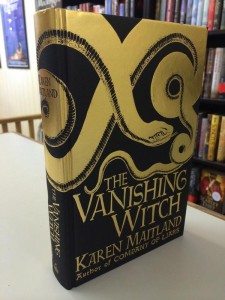

Needless to say, I felt very excited about meeting her again. The subject of her talk at The Collection in August was her latest novel, The Vanishing Witch, set in 1381 during the reign of fourteen-year old King Richard II, focusing specifically on the suppression of the Peasants’ Revolt.

Needless to say, I felt very excited about meeting her again. The subject of her talk at The Collection in August was her latest novel, The Vanishing Witch, set in 1381 during the reign of fourteen-year old King Richard II, focusing specifically on the suppression of the Peasants’ Revolt.

“I always start off with the idea that I’m looking for a modern issue that has got a medieval parallel,” she explained later as we sat in the museum staffroom. She was just as charismatic as I’d remembered and, as we talked, I found myself neglecting my planned questions, too interested in what she was saying to divert the conversation unnecessarily. “In this case,” she said, gesturing at her copy of The Vanishing Witch. “I happened to be looking at the footage from the London Riots in 2011, when I was planning the initial idea for the book. It suddenly struck me that there were many elements of the riots that were a parallel to the Peasant’s Revolt, involving many of the same issues.”

Human nature, Maitland argues, has never changed.

The study of history allows us to examine human behaviour from a comfortable distance, giving us an objective perspective tricky to adopt when analysing problems in the present. Instead of becoming wiser, however, historical records and, indeed Maitland’s novels, demonstrate that humans are consistently unable to learn from their mistakes.

“Although it would be nice to learn from history I don’t think we ever will because we’re never going to change as human beings,” Maitland says. “A point that one of the characters makes in my book is that who ever is in charge is going to be wealthy and the people that aren’t in charge are going to be poor – there’s always going to be that division. I actually do believe that; even in a communist state it’s exactly the same.”

“Like in Animal Farm,” I say.

“Like in Animal Farm,” says Maitland.

“Like in Animal Farm,” says Maitland.

The Vanishing Witch has been the hardest novel to write in Maitland’s career so far and Maitland herself considers it to be her best. Although scenes from the first draft were originally set in Whitby, during the editing process the novel was rewritten, taking place almost exclusively in medieval Lincoln. Sitting in The Collection, in the shadow of the towering Cathedral, once the tallest building in the world, the medieval era doesn’t really feel very far away. It creeps over the cobbles paving the steep hill and lurks in the dark doorway of the Jew’s House, dating from the mid twelfth century, one of the oldest town houses in the country.

You don’t have to find the history in Lincoln – it’s already staring you in the face.

“That’s the wonderful thing,” Maitland says. “You can actually walk the roads that your characters walked. Obviously things have changed but if you walk around, especially at night, when you’re not conscious of shop lights or anything like that, you can imagine your medieval merchant walking up the road or a murder happening in a dark corner.”

Setting is extremely important to Maitland in her writing. I remember her mentioning it the first time I met her; she had wanted to set a scene in a church on the coast but, after visiting the church herself, she realised how windy it was and, as a result, she would have to write about her character clutching their cloak tightly around them as they battled against the gale. This practise seems to have stayed the same:

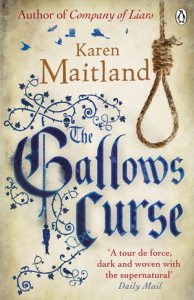

“I always have to visit the places I write about; I have to get a very strong sense of location,” she says. “It’s the third strand of any novel that I write. To me, the place is almost another character. For example, my previous novel, The Gallow’s Curse, is set in Great Yarmouth. In medieval times, Great Yarmouth was an island but it isn’t any more. However, there is a point at which if you lie down on a hill up above it and look down you can actually see the geographical contours and you can see where the ships would have come in, even though they are now fields. It’s just a case of lying down there and trying to imagine that it’s not a field, but water, and therefore at what point would somebody have seen that ship.”

“I always have to visit the places I write about; I have to get a very strong sense of location,” she says. “It’s the third strand of any novel that I write. To me, the place is almost another character. For example, my previous novel, The Gallow’s Curse, is set in Great Yarmouth. In medieval times, Great Yarmouth was an island but it isn’t any more. However, there is a point at which if you lie down on a hill up above it and look down you can actually see the geographical contours and you can see where the ships would have come in, even though they are now fields. It’s just a case of lying down there and trying to imagine that it’s not a field, but water, and therefore at what point would somebody have seen that ship.”

Although Maitland writes about the past, she seems very much engaged in the future. Her next novel, The Raven’s Head is due for release in Spring 2015. Although we may not have learnt how to be better people, or how to run a country, from history, we continue to be fascinated by it. And fascination is a wonderful state in which to live your life. I think Karen’s got the right idea.

Comments