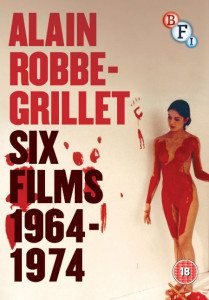

Review: Alain Robbe-Grillet: Six Films 1963 – 1974

Compilation includes:

The Immortal One (1963)

Trans-Europ-Express (1967)

The Man Who Lies (1968)

Eden and After (1970)

N. Rolls the Dice (1971)

Successive Slidings Into Pleasure (1974).

Released for the first time in Blu-ray and DVD formats, ‘Alain Robbe-Grillet: Six Films 1963 – 1974’is a detailed and carefully curated filmography and exploration of the controversial French writer and director. Aside from six of his most definitive films, there is also an array of extra features and interviews, courtesy of the BFI.

Robbe-Grillet is not an instantly recognisable name, which is justified when observing the nature of his work, that is at best highly artistic and experimental, and at worst, obscure and disengaging. As nearly all reference to classical Hollywood film convention is actively discarded, the films are often confusing in their narrative, allowing very little explanation or signposting to the viewer. This is intentional: Robbe-Grillet encouraged the viewer to engage actively in the film, imagining their own answers and creating their own understanding of the films. Whether this intention is successful, however, relies upon the individual audience member. Although a film fanatic armed with a backlog of research on the works of Robbe-Grillet, his contemporaries, and the French New Wave may be able to weasel some pleasure out of the films, it is difficult to imagine a standard multiplex-attending film-goer responding to the compilation with anything but confusion or perhaps even disinterest.

What ultimately must be understood about the Six Films is that one mustn’t approach them as one would approach any film in the popular commercial canon, modern or otherwise. It is far more advisable to evaluate them in terms of artistic merit and historical value. Indeed, visually the films are often fascinating, and had they been of shorter length would not look out of place as a video instalment in an art exhibition. The aesthetic value continuously slides between pleasuring, erotic, and voyeuristic – the visual depiction of women, specifically beautiful women – is clearly of high concern to Robbe-Grillet, and the films are abundant with shots of beauty.

Judging from the collection, it is never a specific plot nor character that Robbe-Grillet aims to explore, but a range of filmic concepts and structural ideas not usually acquainted with the normative cinema of his time.

Due to the artistic and determinedly non-conventional nature of these films, it is challenging to veer one’s impressions of the film contents in an objective direction. As Robbe-Grillet intended, the personal reading by one viewer of any of these films could be drastically different to the next viewer. It is best, then, to comment less upon the narrative content of the films, and instead consider the structural intentions, alongside Robbe-Grillet’s ability to warp recognisable film genre into something far more difficult to catergorise.

Trans-Europ-Express (1967) is one of Robbe-Grillet’s works which draws most comment amongst film critics. It is widely regarded to be a film-within-a-film, albeit deliberately misleading and often shifting in tone, structure and narrative direction. The basic premise appears to be that Robbe-Grillet, as himself, boards a train, and with the help of his producer and assistant, devises a thriller plot for a second film revolving around a drug trafficker, Elias, (Jean-Louis Trintignant) also on the train, taking a suitcase of cocaine to Antwerp. It is not ideal to describe the concept as film-within-a-film, as although Elias’s section is at least initially suggested to be largely controlled by Robbe-Grillet’s, there is not a one-way direction of cause and effect, and both scenarios suffer a shifting amount of influence from the other, though the ‘reality’ of either is permanently in question.

Judging from the collection, it is never a specific plot nor character that Robbe-Grillet aims to explore, but a range of filmic concepts and structural ideas not usually acquainted with the normative cinema of his time. A disregard for linear narrative and a total avoidance of the three-part act are two of the more obvious transgressions in this instance, but the vast array of ways in which he subverts the traditional cinematic format definitely succeed in making the audience reformulate their understanding of what a ‘film’ can be defined as.

Six Films serves as a journey of exploration into a specific pocket of time and location, in which the French New Wave was developing and film-makers were looking to employ new means in which to construct meaning without being constrained by the traditional and recognisable methods of their predecessors. Confusing, challenging, erotic and subversive, this BFI collection emerges as a portfolio of Alain Robbe-Grillet works which will no doubt prove invaluable to certain film academics and aficionados, but likely incomprehensible to the rest of the film-watching community.

Comments